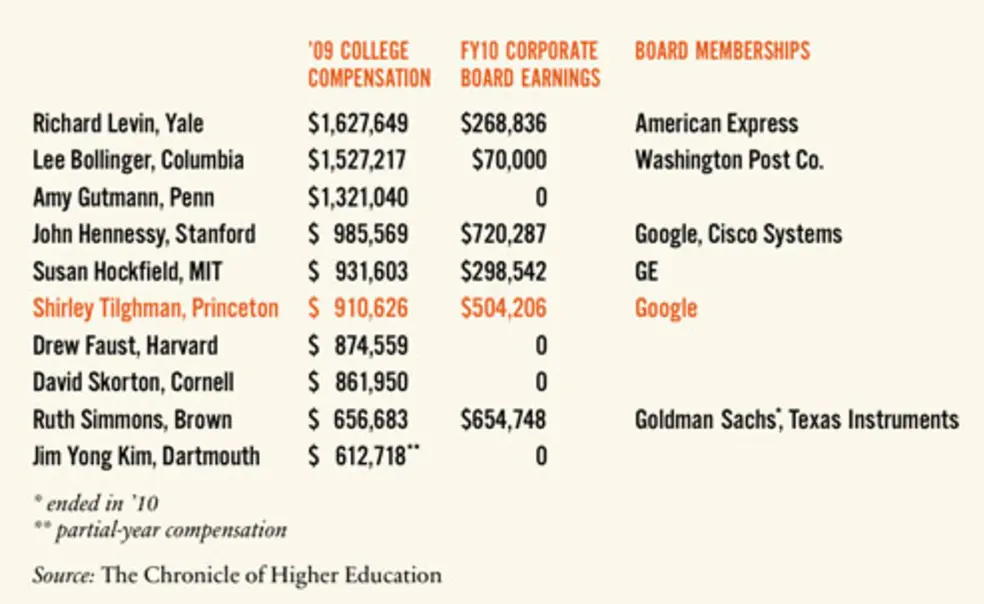

Corporate boards add to college presidents’ earnings

Serving on corporate boards is not unusual for college presidents: Among those who head the 50 U.S. universities with the largest endowments, about a third held a position on at least one company board, according to a survey by The Chronicle of Higher Education. Here are the university compensation totals for 2009 and corporate earnings for fiscal 2010 for presidents of the eight Ivy League schools, plus Stanford and MIT.

2 Responses

John Delaney

10 Years AgoOutside compensation

I was very disappointed to see that chart of Ivy League presidents’ corporate board participation (Campus Notebook, March 7). President Tilghman is comfortably near the top, while four of her colleagues abstain from the practice, presumably for ethical reasons.

When I first came to Princeton 30 years ago as a professional librarian, I wanted to earn some extra Christmas money (nights and weekends in December) for my family at some retail store like Macy’s. But I couldn’t do that: It wasn’t professional, I was an employee of Princeton, and that meant a 100 percent commitment. Apparently, however, certain “regular” outside participation is fine — even for those who you would think really need to give Princeton 100 percent.

It’s the same old story, however you want to define such participation and its purpose (mine was temporary, mercenary, and selfish, of course): Those at the top have different rules and are extremely well-compensated for playing by them.

Laurence C. Day ’55

10 Years AgoTwo hats that don't match

In his letter to PAW (April 25), John Delaney raises an important subject on the outside compensation of President Tilghman as a member of Google’s corporate board.

The president of Princeton is more than well-compensated for a demanding fulltime position that requires wearing a myriad of hats to serve that mission faithfully, diligently, and objectively. To serve on the board of directors of publicly held corporations can create overt and subtle conflicts of interest that can compromise the broad mission or the educational objectives of a university and Princeton in particular. Circumstances often arise in corporate governance that demand complete independence of judgment and action in the interests of shareholders and public policy; these could place a university president in an awkward position and dilute the most objective decisions that should and could be made behind closed doors.

With the pressing time demands on university presidents, there is scant plausibility they have the additional resources required to study, absorb, convene, discuss, conclude, decide, and cast a vote on a corporation’s extensive and rapidly changing issues. In addition, many university presidents do not have the business-educational background and deep industry experience required to be an effective director in corporate matters. That is not to say that once retired from the presidency of a university, they might not make superior members of a board and have the time and will to make the best decisions for the shareholders.

A Princeton University president has the potential to be an effective corporate board member, but not while serving in the primary capacity of leading the University. Wearing two hats that don’t match sends the wrong message. One master at a time is enough.