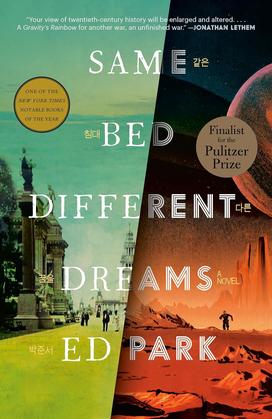

Creative Writing Lecturer Ed Park Reimagines Korean History

The book: In this thrilling meld of history and fiction, Soon Sheen, who is employed by the tech company GLOAT, discovers an unfinished book he believes is authored by the Korean Provisional Government (KPG). Established in 1919, the KPG set out to lead the independence movement against Japanese Rule, but ultimately it dissolved after Japan’s defeat in World War II and the civil war which led to the split between North and South Korea. But what if the KPG still existed? Same Bed Different Dreams (Penguin Random House) explores what could have happened if the KPG remained active and was working toward unifying Korea. It weaves Korean history, American pop culture, and more, revealing a new dimension where utopia is possible.

The author: Ed Park is a lecturer in creative writing at Princeton. His first novel, Personal Days, was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award. Park is founding editor of The Believer and has worked previously in newspapers, book publishing, and academia. His writing has appeared in The New Yorker and Harper’s, among other publications.

Excerpt:

2333: The Scholars (2016)

What is history?

That is the question, that is the job. Might a deeper understanding of history benefit the company, or is it to be avoided at all costs? Teams are told to blue-sky it, whiteboard pros and cons. When you break the word down, what does it tell you? The Latin, from the Greek.

Three telegenic academics discuss it at an all-hands. The first speaker, an American wunderkind, sports a headset with a purple-foamed mic that resembles a levitating gumdrop on the jumbotron.

“History,” she intones as she paces, “from the same Indo-European root that gave us wit.” She mimes tearing out and crumpling her notes, to signal Enough with the old ways. In the last decade, she says, history has toppled from the king of disciplines to a numbing data set: a litany of trackable moments, the realm of machines.

She stands at the lip of the stage. Everything you buy, view, read, and believe gets recorded. Where you drive, how you sleep. Lusts and peccadilloes. Mental lapses, steps climbed. Debits and credits, search terms and activity logs. Only by going off the grid can one enter true history. “Abolish every clock,” she concludes. “Go back to Day Zero.”

A concerned murmur. Is this a dig at the company and its voracious tab keeping? Or will this radical reset somehow help them do their job? The workers clap politely.

Day Zero?” comes a coy query, from the second historian. “Hmm.”

He’s her former adviser. White hair, black eyebrows, with a mustache that splits the difference. Remaining seated, he offers a rambling anecdote by way of rebuttal. Early in his career, while engrossed in some eighteenth-century grain ledgers, he brooded over the meaning of history. One afternoon, sharpening a pencil, he received the answer, a metaphor that perfectly captured his calling. He wrote it down and continued his work amid those humble documents.

Four years passed, as he labored on the monograph he was sure would secure his reputation. Nearly finished, he prepared the coup de grâce: his shattering insight into the true nature of history. Now, alas, the full formula eluded him. After days of searching, he located the slip of paper with the aperçu at the bottom of his satchel. To his horror, a summer storm had reduced it to a blank white scrap. The more he tried recalling the words, the less sure he was about anything.

The crowd takes it all down. A cough booms through the speakers. “My old friend asserts we should avoid metaphor when it comes to history,” sniffs the third panelist, a cheeky maverick of indecipherable ethnicity, gender, and height. “Yet the nostalgic scene he presents is itself a new metaphor, as apt and useless as all others, by his own definition. What is history, you ask? A message from a genius, ruined by the rain.”

For two hours, the scholars spar, drawing on video games, mirror neurons, some minor works of Poe. They speak to be quoted, and the audience sits rapt. For the most part. During the debate, someone secretly records a colleague pinching his own thighs, struggling to keep his eyes open—to no avail. Soon the man is snoring. Onstage, the first scholar booms, “What is history?” The subject wakes with a start, slurps back saliva.

The video gets forwarded, bcc’d, uploaded, liked. The self-pincher’s face is only half visible, but the gist is clear. As the clip makes the rounds, viewers add captions, crude animations. It becomes a sort of folk tale, bristling with embellishment. It speaks to current events, pop culture, the environment. Versions leak outside the organization: jumping borders and slipping into foreign tongues. Spin-offs exist that are not safe for work. This fading, drooling figure in the crowd is part of history, too, even if the official transcript omits the incident.

What is history?

At least for now, it’s a three-way standoff, a memory of rain, a cure for insomnia. These possibilities are duly entered into the system.

Excerpted from Same Bed Different Dreams by Ed Park. Copyright © 2023 by Ed Park. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Reviews:

“Ed Park’s blisteringly entertaining newest entangles a mythic manuscript, a sprawling Korean Provisional Government, and a veteran-cum-sci-fi novelist to brilliant effect.” — Vanity Fair

“I can’t stop reading, thinking, and dreaming about this feverish, mind-altering marvel of a book.” — Hua Hsu, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Stay True

No responses yet