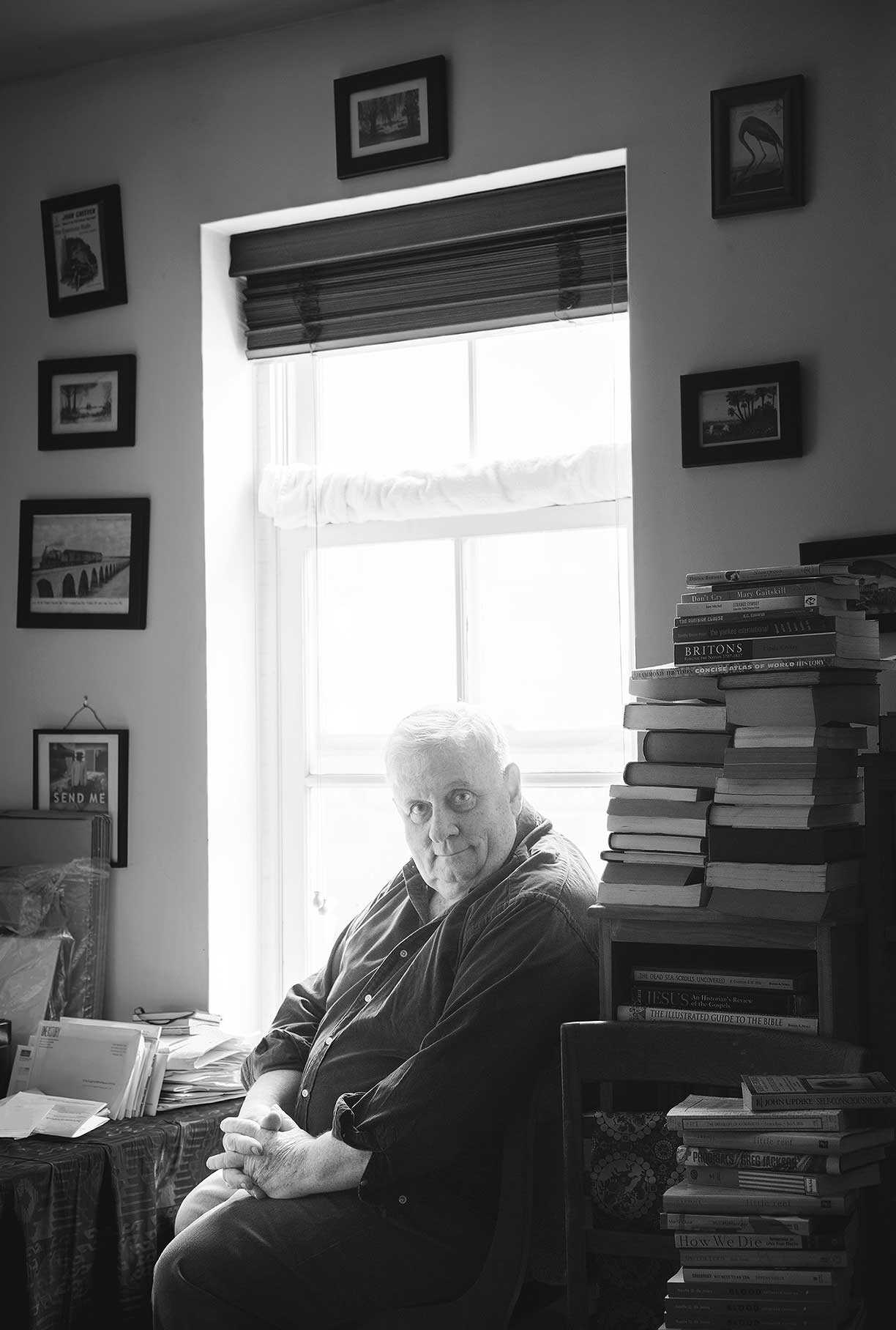

Curriculum Vitae: Professor Edmund White Blazed a Trail in Gay Literature

His novels and memoirs are ‘funny, sexy, passionate, and gorgeously written’

He has stood at the forefront of most of the significant milestones in gay life in the last half century. He co-founded Gay Men’s Health Crisis, an HIV/AIDS service organization, in 1982 and served as its first president. He has been HIV-positive since 1985, and was one of the first well-known figures to speak openly about the diagnosis. He even witnessed the Stonewall riots — though only because he happened to be walking down Christopher Street at 1 a.m. “I’m sort of a mixture of a kind of rebel and a middle-class conformist,” he quips.

At 15, he told his mother, a child psychologist, that he was gay. She sent him to a Freudian psychiatrist in Evanston, Illinois, who declared him “unsalvageable.” The encounter freed him, he says, to chart his own course. After graduating from the University of Michigan, he turned down a spot in a graduate program at Harvard to follow a boyfriend to New York City — one of many examples of his romantic life steering his destiny. A play he wrote in college was produced off-Broadway, and he got a job at Time magazine, working on plays and novels in the evenings. That creative work faced repeated rejections. “I was trying to write for the market,” he says. “Finally, I gave up and thought: I’ll write the novel I would want to read.” The New York Times reviewer called Forgetting Elena “an astonishing first novel” that was “uncannily beautiful.”

“Gay fiction before that, Gore Vidal and Truman Capote, was written for straight readers,” White told The New York Times last year. He and his peers in the gay writers group Violet Quill “had a gay readership in mind, and that made all the difference. We didn’t have to spell out what Fire Island was.”

His 1982 breakthrough novel, A Boy’s Own Story, set in the 1950s, depicts a teenage boy’s struggle to accept his sexuality: “I see now,” the narrator says, “that what I wanted was to be loved by men and to love them back but not to be a homosexual.” The novel is the first installment — along with The Beautiful Room Is Empty and The Farewell Symphony — in a celebrated trilogy of autobiographical works that capture gay life through the Stonewall riots and the AIDS epidemic. “His work is funny, sexy, passionate, and gorgeously written,” says Michael Cadden, a senior lecturer in theater at Princeton’s Lewis Center for the Arts.

White says he has “never liked being political,” but after discovering he was HIV positive, he spoke out about his diagnosis and published some of the earliest gay fiction in English about AIDS, the 1987 collection The Darker Proof: Stories from a Crisis, written with Adam Mars-Jones. “AIDS had been so medicalized,” White says. “As novelists, we wanted to write about what it felt like to have it.”

At 15, White told his mother, a child psychologist, that he was gay. She sent him to a Freudian psychiatrist in Evanston, Illinois, who declared him “unsalvageable.” The encounter freed him.

White’s literary contributions extend far beyond his fiction. His meticulously researched 1993 biography of Jean Genet, a vagabond who scribbled his novels on scraps of paper while in prison, took White eight years to complete. He studied French penal codes and conducted interviews with scores of people. The 730-page Genet: A Biography won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography. White — an avowed Francophile — went on to write critically acclaimed biographies of French gay literary figures Marcel Proust and Arthur Rimbaud.

His other nonfiction has broken ground as well. He wrote the first gay sex manual. States of Desire: Travels in Gay America took readers to dozens of cities, from Memphis to Minneapolis, to chronicle the sexual freedom and political activism that was flourishing in the late 1970s. It was the first book of gay travel writing, according to The Times Literary Supplement. He also explored real-life subjects in his fictional writing, such as the novel Hotel de Dream, which is about a gay novel that White imagines was written by 19th-century author Stephen Crane. His 2006 play, Terre Haute, conjures an encounter between author Gore Vidal and Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh.

He holds back little in his memoirs, where he describes — in graphic detail — the central role that sexual intimacy has played in his life. “Ed believes with a Whitmanesque unabashedness that sex is an instrument of knowledge,” says Jeff Nunokawa, a professor of English at Princeton. “He understands how important it is to take your sexual desires seriously.”

After living in Paris for 16 years, White returned to the United States in 1998 to teach at Princeton, where he was a professor of creative writing until his retirement in 2018.

Two years ago, White received a lifetime achievement award from the National Book Foundation, which called his work “revolutionary and vital, making legible for scores of readers the people, moments, and history that would come to define not only queer lives, but also the broader trajectory of American culture.” PEN America, which gave him a similar award in 2018, praised his “honest, beautifully wrought, and fiercely defiant books.”

And he’s still at it. Last year, at the age of 80, he published A Saint from Texas, a novel that the Times described as “exactly like a stroll through Le Jardin des Tuileries — if the garden had been planted with land mines instead of tulips.” In March, The New York Times Style Magazine published his 2,400-word essay about Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Talented Mr. Ripley and held an online conversation about the book, led by White. And he is halfway through writing his next novel, which, according to its author, is about polyamory, aging, and “a rich Italian who comes to America and has an affair with a character named Edmund White.”

1 Response

Joseph Laibman

10 Months AgoEnraptured by Forgetting Elena

After reading a biography of White, I checked out Forgetting Elena from the U-M library, which I somehow hadn’t read. So enraptured by the first few pages, I (atypically) missed my bus stop. This has happened in my reading history only once before — in the early 1990s, when I was about to give a lecture on the four musical versions of Pelleas et Melisande (Faure’s, Debussy’s, Schonberg’s, and Sibelius’), Thus, I thought it incumbent to read the Maeterlinck. I locked myself out of my car! You are duly honored.