Dan Armstrong ’72 Reflects on Princeton’s Evolution In New Novel

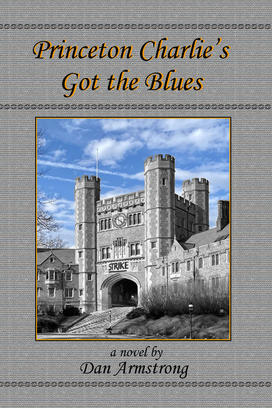

The Book: Princeton Charlie’s Got the Blues (Mud City Press) is a historical novel set at Princeton during turbulent years from the late 1960s to early 1970s. The novel follows the lives of five students, three men and two women, through the ups and downs of political protests, the opening of coed dorms, experimentation with drugs, and individual romances. A conservative, largely white university in 1968 would become something entirely different by 1972. The inclusive Princeton of today is a direct result of the sea changes that occurred during these four years.

The Author: Dan Armstrong ’72 lives in Eugene, Oregon. He earned his undergraduate degree at Princeton in aerospace and mechanical sciences but has focused on the environment, promoting sustainable agriculture in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. He has worked as technical writer, a sportswriter, an editor, a painting contractor, and a novelist. Princeton Charlie’s Got the Blues is his 13th novel. Access to his writing is available at mudcitypress.com.

Excerpt:

The faintest tint of autumn colored the campus on a mild September evening in 1968. The sun, just above the horizon, shone in wide bright streaks through the trees and crenellated towers. Young men, all with promising futures, bustled along in spirited groups of three or four. They were the latest crop of high school graduates soon to get their first taste of what it meant to attend Princeton University. The young men, eight hundred and fifty-three in total, strode along with prep school friends or new roommates, glancing around, appraising their classmates as they made their way to Alexander Hall, where University President Robert Goheen would welcome them to one of the most highly respected private colleges in the world. It was an honor and a privilege to be there.

Many of the students wore tweed sportscoats, slacks, and penny loafers. A few wore ties. Some sported polo shirts with deck shoes. Others dressed in blue jeans with button-down shirts and desert boots. A handful showed off brand new black and orange sweatshirts. One student wore a cowboy hat, another a San Francisco Giants ball cap. And all of them were excited and somewhat anxious about what the next four years would bring, most imagining something momentous.

Perhaps a tenth of these new students came from elite prep schools like Lawrenceville or Choate or St. Paul’s or Andover or Exeter. Some of them knew each other and felt they belonged there. Maybe their father or their grandfather went to the same prep school and then on to Princeton. They were more confident and probably better prepared than most, and quite likely came from wealthy or well-connected families.

The other new freshmen were excellent students as well. Many came from large urban high schools or rigorous parochial schools, accustomed to competition and confident they were there for a reason. Some were top students from small rural high schools where the competition might not have been as tough or the teachers as demanding. Some of them wondered if they should be there at all. Some were geniuses from anywhere USA, with unique talents in mathematics or physics or language, young men with destinies seemingly already written. Some were athletes, also good students but with less glowing grades and SAT scores, worried, perhaps, about the challenges they would face when not on the court or the playing field. Some were outgoing born leaders, who had been student council presidents or merit scholars. Some were introverted, nervous, and shy, hoping to find a niche in the high altitude of the Ivy League. Forty-five were Black. Not nearly as many were Asian. Less than ten were Hispanic. Maybe two were Native American. One was blind, and none were women.

By appearance, the class of 1972 mirrored the changing and uneasy times of the late 1960s. The majority were clean cut typical Princeton freshmen, white and conservative, with short or neatly parted hair, but quite a few sported beards or mustaches and fashionably longer hair. A handful or two had extremely long hair, perhaps sideburns and maybe a string of beads or kicked down the walkway in bellbottoms.

Clouds of cigarette smoke appeared periodically here and there among the clusters of students. Names and catcalls were shouted at random, hey Jim, hey Walt, hey douche bag, as they hustled along to the curious Romanesque auditorium of granite and brown sandstone in the center of campus. A sprawling four-story building, bracketed by two cylindrical, cone-capped towers, Alexander Hall seemed misplaced amid the gothic architecture of the university. A large, round, stained-glass window decorated the face of the building. Below, two brown sandstone arches with their double doors propped open welcomed the new students eagerly streaming in.

The auditorium held nine hundred, with six hundred seats fanned out on the main floor and three hundred more in the wrap around balcony. The stage, large enough for a theatrical performance, was empty except for a podium and five chairs behind it for the speakers. The atmosphere in the building vibrated with a sense of tradition and thrill as the young men found their seats, still assessing each other, some in awe, some looking for faces they recognized.

The Lawrenceville School, six miles south down Mercer Street, had funneled students to Princeton for over a hundred and fifty years; anywhere from fifteen to thirty Lawrentians joined each new class. Twenty or so Lawrentians were in the auditorium on this evening.

Amid the hubbub in the auditorium, one Lawrentian in a gray tweed sportscoat and faded blue jeans with a tear in one knee stood up and called out across the room to a friend, “Barry! Can’t believe they let you in this place.”

“My father still doesn’t believe it, Jack,” the other Lawrentian laughed back. Unshaven for at least two weeks with a Fu Manchu wrapped around his upper lip, he wore a Harvard rugby jersey, madras shorts, and flip flops.

“The question is how long will you last?” returned the other, knowing he and his friend were attracting attention with their sarcasm in the crowd of mostly hard-working wonks and eggheads.

Ned Holms sat a few seats away watching the exchange. He had gone to a public high school in Vienna, Virginia and had never heard of the Lawrenceville School. But he admired the bravado in the young men’s voices and wished he were that relaxed. He was eighteen but looked fifteen with fair hair cut short and brushed over to the right, yet to shave more than a few hairs on his chin. He had won the science award at James Madison High School and knew how to apply himself, but he was somewhat intimidated by what it meant to be a freshman at such a prestigious university. He came from a military family and planned to major in aerospace engineering, because, in an example of how he made decisions, neither a foreign language nor a thesis were required for an engineering degree. Ned watched another young man come down the aisle to a take a seat. His hair was blond, parted in the middle, and long, lying over his shoulders down to the middle of his back. Puffy blond muttonchops, like something from the previous century, added to his distinctive look.

Benjamin Habib, two rows behind Ned Holms, was cut from different cloth. He was Lebanese. His hair was black and his cheeks shaded with a five o’clock shadow. His father had come to America as a boy and now owned an exclusive restaurant in New York City. Benjamin was the first of his family to be born in the United States. He planned to become a heart surgeon. He would take pre-med courses here at Princeton and upon graduation apply to the best medical schools in the country, certain he would get into all of them.

Ten seats to Benjamin’s left was a sober-looking, bespectacled young man with brown hair already receding across his forehead. He wore a tie and a vest with pressed slacks. John Bianchi, much like Benjamin Habib, knew that he belonged there and that he would excel. He would go to Harvard Law School, become a judge in Massachusetts where he grew up, and if things went his way, which they would, he would clerk for a Supreme Court Justice. He observed the others around him, evaluating his classmates in the moments before the speakers appeared on stage. John’s father didn’t go to college. He raised his family of six as proper Catholics on a bus driver’s salary. John could never have come Princeton if not for his perfect grades, elite SAT scores, merit scholar credentials, and a full scholarship from the Navy Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC).

Sitting in the first row of the balcony, Greg Allison, a nineteen-year-old Black student from Wilmington, Delaware, looked down on the white folks finding seats. Although he had gone to an almost entirely white prep school, with his hair in an impressive Afro, he felt like a being from another planet and scoured the crowd for other aliens.

Also in the balcony was David Chou, whose parents came from Taiwan. His black hair was short and parted to one side. He was there to study physics. David was a math whiz, posting eight hundreds in the math portion of the College Board SAT test and the Math Aptitude test as a sophomore in high school. At sixteen, he was the youngest member of the freshman class. He watched all that was going on with a distance even greater than Greg Allison’s. Of the dozen or so Asian freshmen, he was the only one of Chinese heritage. In his own quiet way, he felt superior to all of those around him and knew Princeton was only a necessary passage on his way to opening the secrets of the physical universe.

The buzzing auditorium suddenly quieted. Five men in coats and ties, three in suits, strode onto the stage from the right. Four sat down to allow the Director of Admissions, John Osander, to speak first…

Excerpted from Princeton Charlie’s Got the Blues by Dan Armstrong. Copyright © 2023. Excerpted with permission of the author.

Reviews:

“Great read. Armstrong’s narrative brings forward so many warm memories of times at Princeton in the ’70s.” — Maryann Thompson ’83

“Though his focus is on Princeton University, Armstrong’s attention to setting the larger historical context universalizes the experience of reading this highly engaging novel. Moreover, the myriad Princeton-specific details will reanimate any grad's memories of their time at Old Nassau. Read it. It is a real treat!” — Charlie Patton ’72

No responses yet