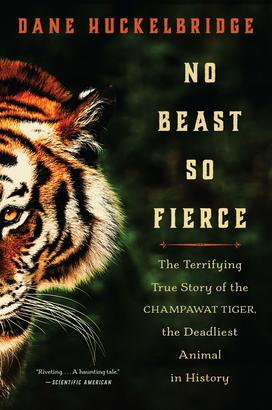

Dane Huckelbridge ’01 Recounts the Life — And Death — of the Most Fatal Tiger Known to Man

The book: No Beast So Fierce: The True Story of the Champawat Tiger, the Deadliest Animal in History (Harper Collins) tells the story of the world’s most prolific feline serial killer and the man who hunted him. Drawing from on-the-ground research, Dane Huckelbridge ’01 gives context to one of the great adventure stories on the 20th century—the story of the Champawat Tiger.

From 1900 to 1907, the endangered Royal Bengal tiger terrorized locals, killing 436 people in the foothills of the Himalayas despite ever-increasing bounties placed on his head. A real-life thriller, No Beast So Fierce follows Jim Corbett, a former railroad employee turned legendary hunter, as he tracks the tiger’s movements, finally confronting him after the gruesome murder of a young woman. Huckelbridge does not end the story there, however — he follows Corbett’s evolution from a celebrated hunter to a devoted conservationist who works to save the Bengal tiger and its habitat.

Opening lines: Where does one begin? With a story whose true telling demands centuries, if not millennia, and whose roots and tendrils snake into such far-flung realms as colonial British policies, Indian cosmologies, and the rise and fall of Nepalese dynasties, where is the starting point? Yes, one could commence with the royal decrees that compelled Vasco da Gama to sail for the East Indies, or the palace intrigues that put Jung Bahadur in the highest echelons of Himalayan power. But the matter at hand is something much more primal—elemental, even. Something that’s shaped our psyches and permeated our mythologies since time immemorial, and that speaks directly to the most profound of our fears. To be eaten by a monster. To be hunted, to be consumed, by a creature whose innate predatory gifts are infinitely superior to our own. To be ripped apart and summarily devoured. And with this truth in mind, the answer becomes even simpler. In fact, its golden eyes are staring us right in the face: the tiger. That is where the story begins.

“The normal tiger,” writes Charles McDougal, a naturalist and tiger expert who spent much of his life studying the big cats in Nepal, “exhibits a deep-rooted aversion to man, with whom he avoids contact.” This is a fact corroborated time and time again by biologists, park rangers, and hunters alike, all of whom can attest firsthand to just how shy and elusive wild tigers actually are. One can spend a lifetime in tiger country without ever laying eyes upon an actual tiger, with the occasional pugmark or ungulate skull the only hint at their phantomlike presence.

However, for the abnormal tiger—that is to say, the tiger that has shed for whatever reason its deep-seated aversion to all upright apes—there are essentially two ways it will kill a member of our species.

The first category of attack is a defense mechanism, a means of protection, and it is employed only when a tiger sees a human as a threat to its safety or that of its cubs. When a mother tiger is surprised in a forest, or when a wounded tiger is cornered by a hunter, its instincts for self-preservation kick in and the claws come out.

There is, however, a second means of attack that the tiger employs when it regards something not as a threat, but as a potential food source—one that relies less on claws than it does upon teeth. They are the most important tools at its disposal for bringing down some of the most powerful horned animals in the world. To crush the muscle-bound throat of a one-ton wild forest buffalo is no easy task, but it is one for which the tiger is purpose-made.

Reviews: “Huckelbridge writes with authority and clarity, deftly weaving strands of economics, sociology and history, explaining how changes to a land and its people upset natural systems that had held for millennia.” – Star Tribune

No responses yet