The Decline of Academic Morality

In a speech to Princeton’s Class of 1979 at the end of Freshman Week, William D. Ruckelshaus ’55 made the revealing remark that one of his main reasons for choosing to come to Princeton was its honor code. Such regard for moral standards strikes one today as almost anachronistic, so pervasive has the cynicism about “old-time” morality become in our post-Watergate era. Perhaps a more accurate reflection of current trends is the recently announced decision by the Johns Hopkins University to abandon its 61-year-old honor code because it was found to be unenforceable. The decision was evidently well-founded: a campus survey disclosed that about a third of Hopkins undergraduates had at one time cheated.

The erosion of moral standards in the academic community has been proceeding for some time in a gradual, barely perceptible way, but it has reached a point now where the evidence for it exists in many forms and is, cumulatively, of disturbing proportions. In this brief survey I draw mainly upon personal experience and knowledge supplemented by experiences others have reported to me, all tending to document the extent to which this decline in academic morality, especially as it affects intellectual property, is seriously undermining the foundations of education in this country.

Theft is the most blatant form such unethical behavior assumes. A particularly striking instance occurred at Princeton last year when an undergraduate was discovered to have been responsible for stealing a set of completed exams with their accompanying grade sheet from the office of a chemistry professor. But this is only an especially egregious manifestation of a form of culpable behavior generally widespread on college campuses. Thus it is common nowadays for campus bookstores and libraries to write off significant losses of books to theft. The items taken are by no means confined to small, easily portable volumes either: a friend of mine who runs the University Press Books store in Berkeley, California, recently informed me that among the books lifted from his shop during the summer was the oversize, heavy (6 ½ lbs.), and expensive ($45) volume published by Princeton University Press entitled The Mythic Image.

I have been told by people I otherwise respect that they see nothing wrong with students “ripping off” books – after all, they say, we live in a capitalistic society that basically “rips off” the underclass, and students (who, on some interpretations, are given the honorific status of revolutionary vanguard of the exploited underclass) are merely responding in kind. Such is the extent to which ideological rationalization can be used to “justify” activity that in any other light would be seen to be simply self-serving.

But students are not the only thieves hiding in the groves of academe. Some of their professors, too, have been known to play the game. Publishers who display books at academic conventions, for instance, no longer are surprised when they find books missing at the end of an exhibit, so accustomed are they now to the pilfering that has become an established tradition at such gatherings of our intellectual elite. Only a few weeks ago five books were stolen from the Princeton University Press’s booth at the American Sociological Association’s annual convention in San Francisco during the last five minutes of the closing day of the exhibit; during the time it took me to track down the sociologist who had walked off with the first book, the other four disappeared from the unattended booth.

It is not only tangible property that is routinely stolen, however, but also intangible property, in the form of works of the mind. Plagiarism is the name given to this type of theft, and in some ways it seems an even more serious offense because more damaging g to the enterprise of intellectual creation. A friends of mine who is employed in a research division of the federal government recently related to me a series of discoveries he had made about the plagiaristic appropriation of this and others’ work. Just by accident he happened upon a book published not long ago by a college professor that used verbatim very substantial portions of articles my friend had written for various journals without putting the material in quotation marks, thus giving the impression that these were the author’s own words.

About the same time my friend learned that a person working towards a law degree at one of our most prestigious law schools had submitted a paper under the pretense that the work was his own, whereas in fact he had misappropriated language and sources from existing studies. And, citing yet another instance, he told of a Congressional staffer who had requested, on the false pretext that his employer needed it for an upcoming speech, a written analysis of a recent case involving tax law that just happened also to be one of the topics of a writing competition sponsored by his school’s law review.

The habit of plagiarism is only promoted, of course, by the proliferation and profitability of companies that specialize in providing essays for students in high school and college to use as term papers. Even at the best universities, apparently, such firms find customers. Last year the Daily Princetonian investigated the appearance of advertisements for a “professional writing and research service” at the University Store and discovered that the company was indeed getting some business from students. There is perhaps a measure of consolidation to be derived from the fact that the purchased papers do not always bring the desired benefit: a paper bought by the Prince and submitted to two professors was judged to be “extremely weak” and “absolutely devoid of ideas.” But this does not mitigate the culpability of the resort to such plagiaristic practices in the first place.

It used to be that Ph.D. degrees were only awarded upon demonstration that the candidate had proved his ability to undertake original research, and it was an unwritten rule that no person would be allowed to write a dissertation on a topic already covered in an earlier dissertation. There is reason to wonder if this standard, too, is not being undermined. Not long ago it came to my father’s attention that a Ph.D. degree had been awarded at his Ivy League alma mater on the basis of a dissertation dealing with the same subject he had written about to win his degree. Examination of the thesis showed that no new evidence had been turned up, no new sources used, and no new interpretation offered. There was a passing reference to my father’s dissertation – enough to show that its existence was known. A letter my father sent to the dean of the graduate school brought a brief and hardly satisfactory reply, to the effect that there was room for many studies of such a subject, ignoring completely the evidence that the work lacked any claim to originality. Such casualness can only devalue further the already much devalued Ph.D.

The slackening of standards at the undergraduate and graduate level is but a prelude to carelessness and irresponsible scholarship later on. A book published two years ago by the Princeton University Press documents in eye-opening detail the extent to which certain influential historians in our country have deviated, whether by negligence or intent, from normal standards of scholarship in the use of evidence. While subsequent reviews have cast some doubt on the seriousness and significance of the alleged misuses for the interpretations offered by these historians, they have not controverted the basic charge that inexcusable slipshod methods of writing history had been employed.

Another sign that responsibility in certain quarter of the academic community has been on the decline is the increasing frequency of procrastination or default on the part of scholars who are asked (and paid) to read manuscripts for publishers. Writing evaluations has traditionally been considered an academic duty, the obligation scholars have to make sure that certain standards are maintained in their fields. Of late more of them have shown a marked proclivity for breaking promises and being late with reports, sometimes very late, or not preparing reports at all. An extreme example in my recent experience is a reader who held on to a manuscript for nearly two years, returning it only in the face of threatened legal action after other appeals had failed – without a report! Such behavior betokens a shocking lack of concern for the rights of authors to have their works reviewed with reasonable dispatch, all the more surprising when one considers that the readers themselves at one time most likely had benefitted from expeditious evaluations of their manuscripts by other readers. Are memories so short these days?

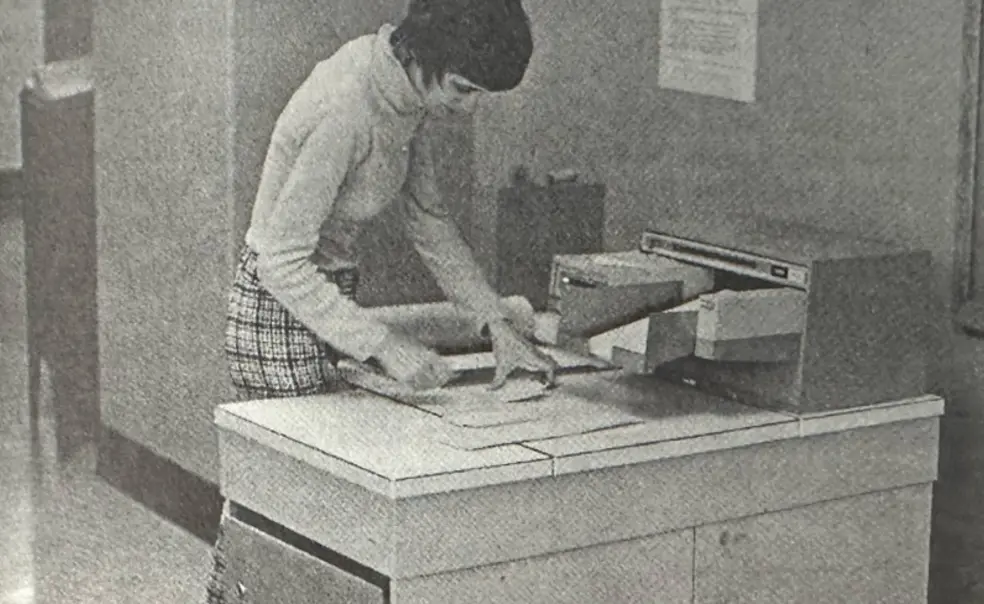

The advent of new technology has opened other doors to trespass on the rights of authors. Appropriation of copyrighted materials without payment has became widespread as photocopying has decreased in cost and duplicating machines have proliferated. Nowadays teachers think nothing of reproducing multiple copies of essays, short stories, poems, sheet music, and other copyrighted works for distribution to students on a regular basis without being concerned that they are undercutting the market which makes the production of such works possible in the first place and also depriving authors of the rightful return that is their due. The attitude that whatever can be had by photocopying should be available free of charge (even though nothing else in education comes gratis, including the use of the machines on which the photocopying is done) makes a mockery of copyright, which was instituted to provide an economic incentive to intellectual creation and to protect the creator’s right to control the use of his property, subject only to the exemptions allowed by reasonable “fair use.”

Today authors and publishers are fighting an uphill battle to preserve what means of protection against the inroads of technology can still be salvaged before the very foundations of the system we have to disseminate knowledge crumble, with consequent loss to all concerned, creators and copiers alike. However well-intentioned the motives for copying may be, its effect if allowed to go totally unrestricted, without having to pay its fair share for the benefits derived, will be to deprive everyone of the fruits of intellectual labor. The creeping malaise that is undermining our respect for intellectual property manifests itself here as elsewhere in the too easy appropriation of the work of others.

What can explain this woeful trend? The answers that immediately come to mind – the pressures of competition, the economic crunch, the easy recourse to ideological rationalization, the over-emphasis on success and getting ahead, with the attendant willingness to cut corners – somehow seem less than fully satisfying. I am not a religious person in the orthodox sense, but I can’t help wondering if our society has not lost touch so completely with the realm of transcendent spirituality, a dimension larger than the sum of human interests considered subjectively as individual preference, that no solid foundation exists any longer for a sturdy morality of principled behavior. “Ripping off” is the new moral chic, and opportunism the basic guide to action, as Watergate so well revealed. If we can’t depend on our institutions of learning to reverse the tide, as the evidence above so depressingly suggests, then where can we turn?

-

PAW welcomes essays of “Opinion” from alumni on topics of general concern to the university community. This week’s writer is social science editor at the Princeton University Press and currently serves as chairman of the Copyright Committee of the Association of American University Presses. – Ed.

This was originally published in the October 13, 1975 issue of PAW.

No responses yet