Former Texas governor Rick Perry’s description of Austin as “the blueberry in the tomato soup” was as apt as it was unappetizing.

For years the capital city stood out as a dot of Democratic blue in a sea of Republican red. But like much of the rest of the country, several large Texas cities and suburbs have turned left, making the state, if not quite purple, at least a strong magenta. To update Perry’s metaphor, the Lone Star State’s politics today might be said to resemble a blueberry pancake.

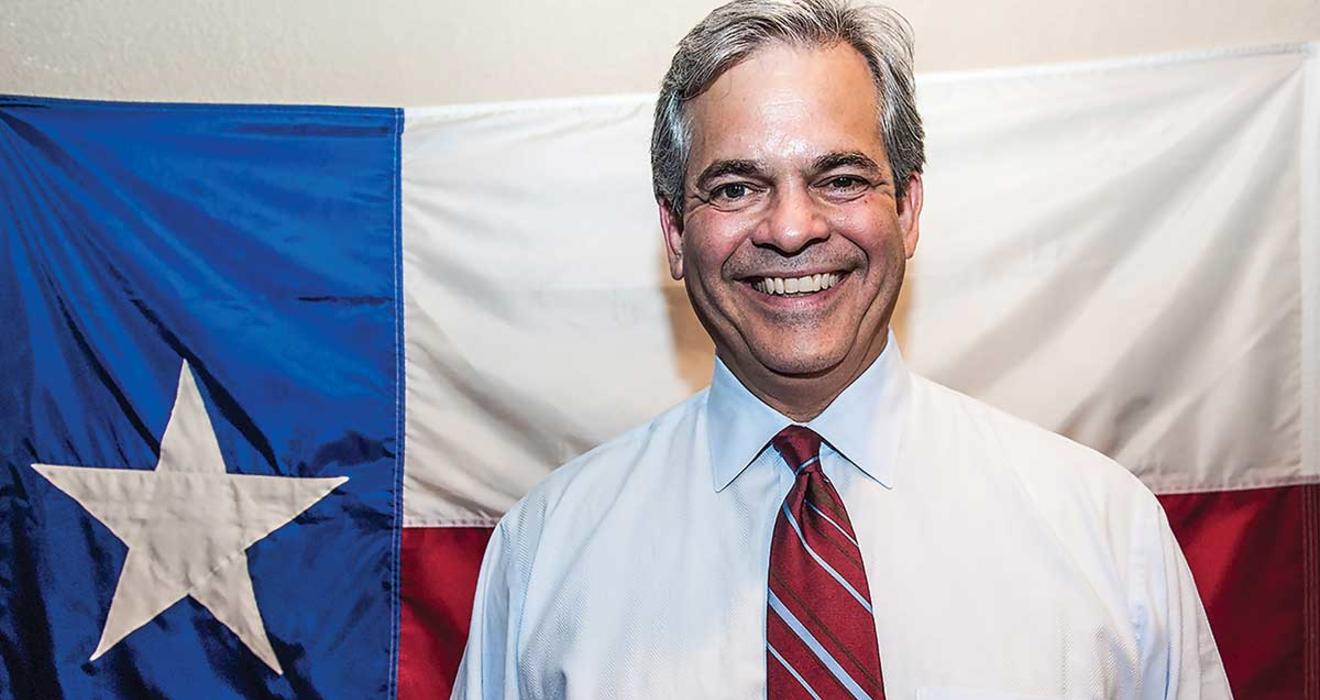

Two of the largest cities in Texas are governed by Princetonians. Since 2019, Eric Johnson *03 has been the mayor of Dallas, the country’s ninth-largest city, with a population of 1.3 million. Steve Adler ’78 is finishing his second term as mayor of Austin, the country’s 11th-largest city, with a population of about 995,000. Both are Democrats, although like most Texas mayors, they ran without party affiliation.

In many ways, Johnson and Adler have jobs that other big-city mayors would envy: Dallas and Austin are among the fastest-growing cities in the country. Historically, Dallas is more conservative and corporate, the headquarters of Nieman Marcus, Texas Instruments, and Southwest Airlines. Massive Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport, which lies outside the city limits and is bigger than Manhattan Island, is the state’s second-largest driver of economic growth. Austin, on the other hand, has become a tech hub, host of the annual South by Southwest cultural conference and, by its own boasting, the live-music capital of the world. For many years its unofficial motto has been “Keep Austin Weird.”

But if the cities differ in background, temperament, and their approaches to important issues, so too do their mayors. They offer a good lens for looking not only at challenges faced by cities around the country, but at different approaches to governing.

“Heyyyy, Eric!” the man behind the counter at Black Jack Pizza in south Dallas shouts when the mayor walks in for lunch. Seeing a reporter in tow, he quickly corrects himself.

“Oops — I guess it’s Mayor Eric now.”

Johnson is a big, personable man, but unlike many politicians he seems content not to be a trailblazer. He is not the first Black mayor of Dallas, for example, but the second. He is not even the first Eric Johnson to hold the job; a man named J. Erik Jonsson was Dallas mayor from 1964 to 1971. Eric Johnson has Erik Jonsson’s bust on a shelf behind his office desk.

At Black Jack Pizza, though, Johnson is a celebrity. He has been eating there since he was a teenager, but now staff members eagerly line up for photos with him, even though they already have several. Johnson is someone who builds connections and keeps them, and perhaps no place shows that better than this one. In high school, when he started dating the daughter of a state representative, Johnson secured an internship in her father’s office so they could see each other. His girlfriend ate at Black Jack, so Johnson did, too, and when he learned that her mother liked anchovies on her pizza, he began ordering his the same way. Johnson ended up marrying a different girl from the same high school but he still eats at Black Jack — and he still gets anchovies on his pizza.

The son of a truck driver and a government secretary, Johnson grew up in this same working-class neighborhood, but from second grade on he attended private school on a scholarship and then graduated with honors from Harvard as a history major. His early career seemed to straddle his two worlds as he worked as an investment banker and as an intern for the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund. He went on to earn a law degree from the University of Pennsylvania and a master’s degree from Princeton’s School of Public and International Affairs.

In 2010, after practicing law for several years, Johnson was elected to the state house of representatives and reelected to five more terms. He took pride in his ability to get legislation passed, even in a heavily Republican chamber. In 2019, for example, he succeeded in having a plaque honoring the Confederacy removed from the wall outside his capitol office after securing a favorable legal opinion from Republican state attorney general Ken Paxton and support from Gov. Greg Abbott.

That same year, though secure in a seat he could have held indefinitely, Johnson became the last of nine candidates to enter the Dallas mayor’s race. Asked why he decided to run, he answers coyly, “It was obvious as the race was heating up that we had a lot of candidates for mayor, but we didn’t have the right candidate for mayor.” More seriously, he says he concluded that being mayor would be a more rewarding use of his time than remaining in the legislative minority. Building an organization on the fly, Johnson finished first in the general election and then won a runoff, 56-44 percent.

In office, Johnson has carefully chosen to focus on what he considers the core responsibilities of municipal government — the things, in other words, that are uniquely the city’s duty to deliver, such as sidewalks, parks, and libraries. “City government is about service delivery,” he reasons. “There are certain things a city does where there is no backstop. There is no backstop for sanitation. If we don’t pick up your trash on schedule and do it well, there’s no county or state or federal trash service.”

In this light, Johnson has resisted discussions in the city council, of which he is a member, to add programs such as after-school care, arguing that it is not something the city could do well and that such programs should properly be funded by other parts of government such as the school board, which is an independent entity.

“What makes you think that a city that can’t pick up trash well will do well at after-school care?” Johnson asks rhetorically. “And where do you think we’re going to get the money for that except through taxes? And if we do that, how many [city residents] do you think are going to stick around as opposed to saying, ‘I’m out of here. I’m going to Frisco [a Dallas suburb] where the tax rate is one-third?’”

Close your eyes, and you can hear a Reagan Republican saying this, but that last point is at the front of Johnson’s thinking. The Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex may be booming, but after decades of driving the region’s economic growth, the City of Dallas now faces competition from its smaller neighbors such as Frisco, Arlington, McKinney, and Plano, which have lower taxes, better services, and less crime. Johnson successfully pushed the council to create a new city-based economic development office and to provide discounted services to attract entrepreneurs starting new businesses.

Mark P. Jones, a fellow at the James A. Baker III [’52] Institute for Public Policy at Rice University who studies Texas politics, suggests that the need to keep Dallas economically competitive has helped shape Johnson’s approach to many issues. “While being a partisan Democrat might help him win elections,” Jones says, “in terms of working with the business community, obtaining investment, and preventing flight of Dallas-based businesses, he needed to maintain a positive and productive relationship.”

Perhaps Johnson’s most controversial decision was his rejection of efforts to defund the police. He expressed support for local protests after the murder of George Floyd until they turned violent. More significantly, he voted against the council’s plan to cut $7 million from the police budget and reduce overtime pay by 25 percent. Instead, the mayor challenged the city manager to “defund the bureaucracy” and cut staff in city hall to offset tax revenues lost during the pandemic.

By a 9-6 vote, the council approved the policing cuts anyway, but Johnson refused to let the issue rest. He denounced the decision repeatedly and last summer convinced the council to adopt a new budget that not only restores the overtime money but will hire 275 officers, raise salaries to keep police from taking jobs in better-paying suburbs, and even buy new squad cars. “This is very much an Eric Johnson public-safety budget,” he says proudly.

Still, the policing battle has left scars. Although Johnson praised the “zeal and enthusiasm” of those who marched for racial justice in the summer of 2020, he now speaks bitterly about “the woke mob” for picketing outside his house and, Johnson says, deliberately intimidating his young children. He recently called for citizens to express as much outrage about the surge in violent crime as they have about police violence saying, “If Black lives are going to matter, Black lives have to matter.”

At bottom, Johnson blames the party’s activist wing for becoming deaf to what most city residents, including working-class people of color, actually want.

“They jumped out on an idea — defund the police, in some cases dismantle the police,” Johnson says. “They took it to the people saying, ‘Isn’t this a great idea?’ And you know what the people said? ‘No, that’s actually not a great idea. Have you seen my neighborhood lately? Have you seen the crime statistics? They’re through the roof.’ ”

A little less than 200 miles down I-35, in the capital city of Austin, the original blueberry, Mayor Steve Adler has reached different conclusions about policing as well as several other issues.

Perhaps nothing better illustrates the cultural differences between buttoned-down Dallas and bohemian Austin than their city halls. Dallas’ city hall was designed by I.M. Pei. Austin’s city hall has a 45-foot-long triangular balcony, known as the “armadillo’s tail,” that juts out over Second Street. The building’s interior is no less quirky. In a central hallway, one art installation is of two life-sized buzzards, made of Legos, pecking at a telephone.

Adler lives with his wife, a real-estate developer, in the W Hotel downtown. Soft-spoken in person, he is more vocal on social media. Gov. Abbott and the state GOP have made Adler and the rest of the “People’s Republic of Austin” into avatars of the Texas Democratic Party, much as Republicans try to make Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez the face of the party nationally. Whatever the GOP has thrown at him, though, Adler throws right back.

Where Johnson has steadfastly remained nonpartisan in office, even declining to endorse anyone for president, Adler was an early supporter of Pete Buttigieg in the Democratic presidential primaries and has been whispered about for a job in the Biden administration after he leaves office. He is often the go-to mayor on MSNBC.

He seems suited to the Washington, D.C., area, where he grew up. Adler’s father was an editor at CBS News, and Adler remembers getting to sit in the studio when Walter Cronkite would broadcast there. After Princeton, where he captained the fencing team, Adler attended law school at the University of Texas because it had the cheapest tuition. As with many others, he fell in love with Austin and decided to stay.

For the next three decades he built a legal career in the private sector, specializing in employment discrimination and eminent-domain cases, and also served on numerous local boards and nonprofits, including the ballet and the Anti-Defamation League. The 2014 mayoral race was his first attempt at elected office. He says he decided to run after his wife chastised him, “Run or don’t run. But if you don’t, don’t ever come home and complain.” Adler raised more than $1 million dollars and, because of his wealth and civic connections, was attacked from the left as being a closet Republican.

“I wasn’t,” he says, smiling, “but all the Republicans voted for me.” He won a runoff with two-thirds of the vote and was re-elected easily in 2018.

In office, Adler has achieved some significant policy victories, most recently persuading voters to approve a referendum that will increase property taxes to pay for a huge expansion of the city’s rail and public transportation system, something he says is essential to ease congestion in a rapidly growing city. (Similar referenda in two other left-leaning areas, Portland, Oregon, and Gwinnett County, Georgia, failed.)

While Adler laments that too many things, such as vaccinations and mask-wearing, have become politicized, Austin is a very progressive city — and the mayor has aggressively pushed a very progressive agenda, even if it sometimes goes further than moderates, including some in his own party, might prefer. “Some fundamental change requires disruptive action,” he explains in a follow-up email. “That has the advantage of moving the public discussion, but the associated disadvantage of creating some measure of uncertainty and concern,” he says, and “the uncertainty of big change” gets weaponized.

Two of those disruptive changes, efforts to fight homelessness and revamp the police budget, have met with mixed success. In 2019, Adler supported the council’s decision to rescind a longstanding city ordinance against camping in public spaces. Though partly driven by COVID, the city’s homeless population swelled, prompting complaints of blocked sidewalks and disruptive behavior. Adler insists that the policy did not increase homelessness but only made it visible, and that doing so was in fact necessary to spur people to action. It did spur action, but not the kind the mayor hoped for. In May, city residents voted overwhelmingly to reinstitute the ban.

Following the George Floyd protests, Austin eliminated $3 million in police overtime pay, canceled three sets of training classes for new officers, and reallocated about $20 million of the $150 million police budget to different uses, such as increasing the number of first responders with backgrounds in mental health. Adler bristles when this is called “defunding the police” and notes that Austin’s police force is among the best paid in the state.

From a strategic standpoint, Adler had been trying for years to rethink the city’s approach to public safety. The protests presented him with an opportunity to do something ambitious, and he grabbed it, learning a valuable lesson in the process. “You can’t do big things incrementally,” he says. “You have to do it disruptively and then try to hold onto it.” Whether he can do that is an open question.

“I am torn between the admonition that you should never pass substantial change with a very close vote, and knowing that, if you actually want to make change, it can’t happen incrementally.” — Steve Adler ’78

“About a third of the Austin population loathes Steve Adler,” observes Jones, at the Baker Institute. “About a third loves him, and the rest are in between. But that third who loves him turns out to vote.” As evidence, perhaps, a group called Save Austin Now placed a referendum on November’s ballot that would have undone most of the policing cuts Adler and the council made. The referendum was backed by the chair of the county Republican Party and three former Austin mayors, but voters rejected it by a 2-to-1 margin.

As if being the state’s most vocal progressive didn’t make him enough of a target, Adler’s detractors have seized on some highly publicized missteps, such as his vacationing in Mexico last year in the middle of the city’s COVID spike, during which he recorded a video urging city residents to stay indoors. He has apologized for setting a bad example.

One characteristic of the “weak mayor” form of government that Dallas and Austin have in common is that the mayor has only one vote on the city council. Asked where their power comes from under such a system, both point to the bully pulpit. As Johnson puts it, “No one knows who the city manager is, most people don’t know who their council member is, but they all know who the mayor is.”

The two mayors know each other professionally and, although they have sometimes differed on policy, each acknowledges the other’s good faith in dealing with the political, social, and economic exigencies in their respective cities. Both deny that their political philosophies have changed in office. But they seem to represent two distinct models for governing.

Johnson, who has sometimes been criticized for high handedness in dealing with critics, decries the corrosiveness of excessive partisanship. “The folks we used to praise were the people who could get Republicans to go along with their ideas and work out deals and compromise. The days of elevating those people are over. Now the people we’re supposed to look up to are the ones who refuse to compromise.”

“Maybe they’re right,” he shrugs. “I just think that they aren’t.”

Adler seems to have found that on many issues, in today’s political climate, there often is no common ground to be found. He is determined to push ahead anyway.

“It is hard,” Adler admits, “but the fact that it’s hard is not an excuse to stop trying. You can still get stuff done.” Even though they have demonized him, Adler has pushed too many reforms for state Republicans to torpedo all of them. The city no longer prosecutes low-level marijuana offenses though marijuana remains illegal under state law, for example. When Republicans stripped Austin of its power to fund Planned Parenthood, Adler and the council shifted the money to provide travel, lodging, and child care for women seeking abortions. How that will fare under the state’s new and even stricter abortion law remains to be seen.

Still, with only a year left in office, there is much Adler wants to accomplish, and he is impatient.

“I am torn between the admonition that you should never pass substantial change with a very close vote,” he says, “and knowing that, if you actually want to make change, it can’t happen incrementally.”

Sometimes, the mayor says, with the wisdom earned from hard experience, “the two are in tension with one another.”

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

This story has been modified slightly for clarification.

3 Responses

Terry Sadowski ’84

4 Years AgoCompelling Portrait of Two Mayors and Their Cities

As a former resident of Dallas, I also considered Austin my hometown for over two decades. Mark Bernstein ’83 captured the essence of these two metropoles and found the sweet spot that exists between the various political factions in each. He also reflected the pragmatic progressivism of mayors Eric Johnson *03 and Steve Adler ’78 while still finding space to expand on the third-rail issues of each city. Well done!

Barbara Trevino Chester ’97

4 Years AgoThank You for Shining a Light on my Home State Mayors

I was so pleased to see such a great article about Tigers leading change in Texas (“Deep in the Heart of Texas,” December issue). As a proud Texan (and member of the Princeton Texans club as an undergrad), I am often asked if there were a lot of Texans at Princeton. My response is always, “There are never enough Texans anywhere.” Kudos to the editor for choosing to make this the cover story and to the author for highlighting some of our finest.

Samuel S. Williams ’57

4 Years AgoInsightful Work

I sent this to the mayor of Charlotte. It is what journalism is all about. I can only hope she will read it — knowing her, she will.

Keep up the insightful work.