Diary of Stewart M. Robinson ’1915 *1918 Offers First-Hand Account of War

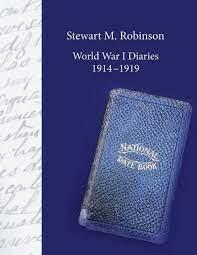

The book: After discovering the diaries of their late grandfather, the grandchildren of Stewart M. Robinson ’1915 *1918 collaborated on a project to publish the daily entries. The book Stewart M. Robinson World War I Diaries 1914-1919 (Lulu) offers a detailed look into the mind of a man throughout the war. Entries range from the mundane, like what Robinson had for breakfast, to the spiritual where he writes through prayer and dark moments. The book starts with an introduction and a foreword by his grandsons David A. Robinson and William Courtland Robinson. His granddaughter Margaret S. Anderson did the cover design and layout, and great-granddaughter Kelly Robinson proofread. The book also includes photos and illustrations that help illuminate Robinson’s experiences.

The authors: Stewart M. Robinson ’1915 *1918 earned both his undergraduate and master’s degrees in religion from Princeton. He served as a U.S. Army Division Chaplain and burial officer in the St. Mihiel and Meuse Argonne campaigns in 1918. After the first World War, he became assistant pastor of the Second Presbyterian Church of Cleveland, Ohio. He also served as chairman of the General Commission of Chaplains, to assist the U.S. Armed forces in screening chaplain aspirants for appointment. Robinson died in 1965 in Delhi, New York.

Excerpt:

Foreword by William Courtland Robinson

This is the war diary of a young man, newly married (September 1917), newly ordained as a Presbyterian minister (January 1918), newly commissioned as a military chaplain (May 1918), who shipped out of Hoboken, N.J. on the troop transport ship, USS Covington, on June 14, 1918 and arrived in Brest, France about two weeks later. By the third week of July, he was assigned to the AEF 78th Division a few miles from the Western Front. He had just turned 25.

Stewart MacMaster did not want to be separated from his young bride, Anne MacGregor, whom he loved dearly and who was expecting their first child (twins as it happened) when he shipped out. But, as he wrote on one of his last days in Delhi, N.Y., going off to war “for so long now…has been only a thing to hear about and to see others doing from time to time. So goes life and we do the duty before us…we face an unknown future with a bold heart.” One month later, he wrote in Chaumont, France: “the war is a fearful thing. Its horror broods over me if I stop to think about it. I am trusting in God to bring me back to my dear ones as I believe He will.”

He was in the war for only a short time. By November, the Germans had signed the Armistice of 1918 in a train carriage near Compiegne Forest, ending World War I. Stewart MacMaster was home in the US and honorably discharged by March 1919. But in less than nine months, he witnessed a lifetime’s worth of suffering and dying, and he and his dear ones were not entirely spared.

He did not know its full significance at the time but he was at the St. Mihiel Salient for the “Great American Offensive” in mid-September 1918, the first US-led offensive in the war, and an important, though costly, victory. On September 12, at 1:00am, he “listened with mingled feelings to the thundering of the guns. I did not sleep much.” That evening, “I saw at least 3000 Hun prisoners marched back. It was an impressive sight.” He also worked on “getting our cemetery established” and buried an American officer on the battlefield the next day. He “rode home by moonlight past the crashing of our big guns.”

The next day, “I was out gathering the dead and I found all too many. They were a sad spectacle…. I feel so sorry for the poor folks at home who will hear of these dead I buried.” Later, “The awful work has begun. Sadness and fear will be rolling across the ocean now as news of these deaths confirm the fact that we are in the line. There are stern experiences ahead. We need grace to stand them.”

By September 20, Stewart MacMaster wrote, “I have a miserable cold in the head and feel a bit mean for that reason. Now I am going to bed.” Three days later, “the doctor pronounced my case to be influenza and I was shipped off in an ambulance to our Field Hospitals…there are real American nurses!” His case was a relatively mild one though he stayed at Base #26 Hospital in Allerey-sur-Saone for a week or more, then was sent to a chaplain’s school at Chateau d’Aux and did not return to the 78th Division until the middle of October. On his return, he received a cable informing him that Anne MacGregor had also fallen ill with influenza and that she had miscarried twin baby boys. Perhaps the cable was not clear about the number of children—in a letter to Anne MacGregor dated October 20, Stewart wrote of his sorrow at the loss of “those three little beings.”

Thousands of miles and an ocean apart, they both were caught up at the same time in the deadliest spike in the “Great Influenza,” the “Spanish Flu,” the “Mother of All Pandemics,” which killed an estimated 50 million people worldwide from 1918-1919. The peak of the mortality, in the United States certainly but in many other countries as well, was between August and November, 1918. The most at-risk groups included adults over 85, children under 1, and adults between 25 and 34. Stewart MacMaster and Anne MacGregor, in other words, were not protected as young adults—they were especially vulnerable, and quite fortunate (as are we, their descendants!) that they survived.

For Americans serving overseas, the influenza traveled with them on the transport ships. As burial officer for the Division, Stewart MacMaster witnessed this up close. His November 6 entry from Lambezellec, France, where he presided over a funeral, was: “There are thousands of graves out there of men [who] had influenza and died when they landed there.” He had eight more funerals at Lambezellec over the next few days and also ministered to the sick in hospital. It was not until a November 21 entry that he writes of his own losses: “Hoping and praying that I may soon be on the way home to Anne MacGregor. She has been wonderful about it all but it is so pitiful to think of her having lost our babies.. I don’t think that I have come to realize yet just how great a loss she suffered, alone and waiting.”

Stewart’s diary in the months that followed were filled with what he called “small duties,” “various odds and ends,” and “weary days of waiting” for the signal that he could go home. Christmas passed, then New Years, then more weeks of waiting for departure orders. On February 9, 1919, he wrote: “This is about the day that would have been the birth of two sons. I did not deserve to be the father of such wonderful creatures but they are mine waiting beyond the skies.” Finally on February 23, he boarded the USS Mongolia and sailed for home, arriving in New York harbor on March 7 where he took a train home to Philadelphia. On March 11, he returned to Camp Dix, NJ where 1st Lieut. Stewart M. Robinson, Chaplain unassigned, Casual Officers Detachment received his letter of honorable discharge and noted in his diary: “At last I am separated from the Army fully and am a plain civilian out of a job. All this has a great deal of joy in it.”

A quote often attributed to Mark Twain goes: “history doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes.” Just over 100 years ago, the world was engulfed in a deadly global pandemic and a world war in Europe. The 1918 flu epidemic infected around 500 million people, one-third of the world’s population, of whom around 50 million died, including 675,000 Americans. World War I mobilized more than 65 million armed forces, of whom 8.5 million died, including 116,000 American soldiers.

Now, as of April 2022, COVID-19 has infected nearly 500 million people (about 6 percent of the world’s population) and deaths worldwide exceed 6 million, including 1 million in the United States. Vaccines, better health and sanitation, and somewhat more effective public health responses worldwide have prevented even more deaths, but ignorance (some intentional) and persistent inequality constrain progress. Meanwhile, the Russian attack on Ukraine in February 2022 has raised the threat of a third world war in Europe, even as it pulls attention and resources away from other protracted humanitarian crises in Syria, Yemen, Somalia, Ethiopia, Myanmar and other low and middle-income countries.

What lessons, if any, can we take from this young man’s diary of his life during plague and wartime? Do your duty, facing the unknown with a bold heart. Keep the faith, I believe he would say, Christian would have been his undoubted preference, but I think he would be more ecumenical than that. Keep a record, certainly, bear witness, and share what you have seen. Make your life “amount to something” as he seemed to think it had in the war: “I have added to my list of experiences and gained, I trust, somewhat in grace and knowledge of God and man.” Then go home, go out, and share that grace and knowledge with love and humility. Then all this—this living and even this dying that we will all do—will have, in the end, “a great deal of joy in it.”

Reprinted with permission from Stewart M. Robinson World War I Diaries 1914-1919. All rights reserved

No responses yet