Dressing up; open talk

The laboratory door slammed behind Justin Brown GS as he rushed across campus, black bow tie in hand. It was nearing 6 o’clock on Thursday evening, and the physics Ph.D. candidate was headed to dinner at the Graduate College.

He burst into the coffee lounge, shaking raindrops from his umbrella, and greeted a small gathering of tuxedoed men and elegantly attired women. “I’m sorry I’m late,” he said. “You all look wonderful.” The occasion was, simply, Thursday.

The students were gathered for the first Formal Thursday of the academic year. Every week, they don formal wear for dinner in Procter Hall amid their casually dressed peers. Most of the attendees are regulars, a group of friends who love the wackiness of wearing black tie to the dining hall and the excuse to carve out time with one another.

“Formal Thursday is a revival of an old tradition,” explained Brown over a meal of slow-roasted turkey and rice. “Until the early 1970s, students wore academic garb to dinner.”

Brown’s friend, Samuel Taylor *10, came across a book about the practice of formal dining at Princeton. In its spirit, he established Formal Thursdays and invited his friends and anyone interested to attend.

The group’s jocular spontaneity inspires occasional thematic twists. When the boyfriend of computer science grad student Ana Pop was away one week, the group kidded about surprising him with a mock wedding. On the appointed Thursday, he found Pop in a bridal gown, surrounded by her wedding party. The group held a ceremony and entered Procter Hall to find that Dining Services had arranged a candlelit table setting, complete with a wedding cake and wine. A few months later, the two were engaged.

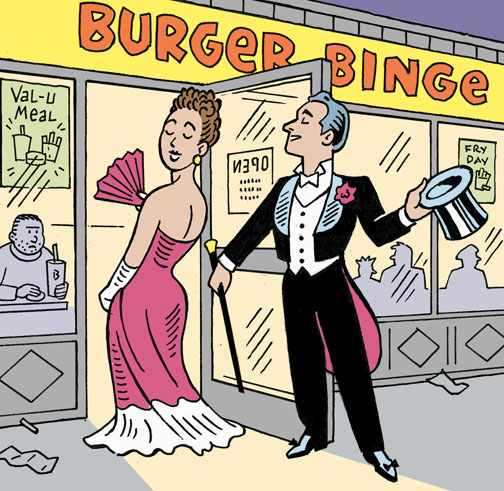

Procter Hall’s history may have inspired the idea, but the formal dinners move beyond its doors. The group has gathered at Hooters, Magma Pizza, and Friendly’s —“wherever it would be strangest to eat in formal wear,” explained Jeffrey Dwoskin *10.

A penchant for silliness fuels their interactions, and each adventure creates another shared story. “For us and those around us, the dinners have become an important part of our lives,” Brown said. “When my boss sees me leave the lab in my tuxedo, he says, ‘Oh, it must be Thursday.’ ”

By Angela Wu ’12

Among college campuses, Princeton is not known for its volatility. Protests are few and far between, and students are more inclined to organize thoughtful debates than they are to lock arms in front of Nassau Hall. Last year, however, when Nonie Darwish, a controversial critic of Islam, was invited to speak by a student group, the tension on campus was palpable.

The group, Tigers for Israel, later canceled the appearance, after Muslim students raised concerns with Imam Sohaib Sultan, a Princeton chaplain. (Darwish spoke on campus at a later date.) Sultan then spoke with Rabbi Julie Roth, the executive director of the Center for Jewish Life and a friend.

“We’re able to talk to each other honestly and openly about our concerns,” Sultan said. “That’s especially useful when there’s a time of potential conflict or tension between our communities.”

The two are teaching a semester-long noncredit course on war, reconciliation, and peace, aimed at bringing Jews and Muslims together to learn about both traditions — and each other.

“It’s important to have these types of conversations in non-sensationalistic contexts, especially at universities,” said Usaama al-Azami GS, who attended one of the classes.

The class draws about a dozen students each week who gather over dinner at the Center for Jewish Life. The tone of the discussion, which brings up issues associated with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, tends toward the scholarly rather than combative. “It touches on the conflict, but is grounded not in politics, but in the religions,” Roth said.

As students discuss sacred texts and raise questions about Judaism and Islam, they often uncover surprising similarities. “There isn’t always communication between the Muslim and Jewish communities,” said Shaina Watrous ’14. “It’s important to hear about these things from the people who believe them, and not just reporters.”

The class, which Roth and Sultan hope to propose as a freshman seminar, is one of several initiatives meant to improve the relationship between Princeton’s Muslim and Jewish communities.

“On college campuses, dialogue is the way that people are able to open their horizons to new ways of thinking,” Sultan said. “When people actually sit down to talk, only then will they come to realize any sense of common purpose and common dreams.”

No responses yet