Economics: A Class in Peril

‘Deaths of despair’ on the rise among Caucasians without a college degree

This story has been updated to correct and clarify descriptions of the findings related to the mortality rate for white non-Hispanics between the ages of 50 and 54 with a high-school diploma or less.

Back in 2014, Anne Case *88 and Angus Deaton — professors of economics at Princeton who are married to each other — stumbled across a surprising finding. They discovered that death rates for middle-aged white Americans were rising, in contrast to the death rates for African Americans and Hispanics, which were declining.

The paper they published the following year was front-page news and sent shockwaves through nascent political campaigns. Now, Case and Deaton have a new paper that adds two more years of data to their findings, including attention to non-white Americans and Europeans and an expanded focus on the role of educational attainment in shaping outcomes.

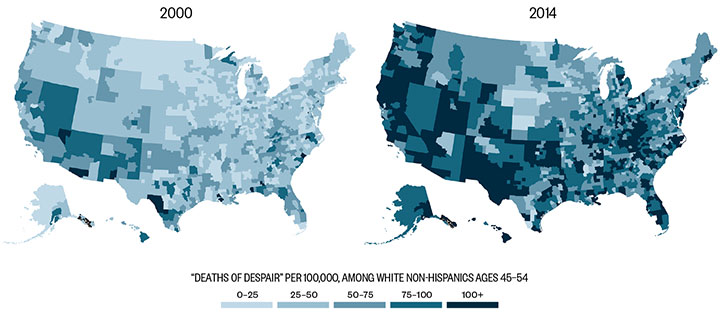

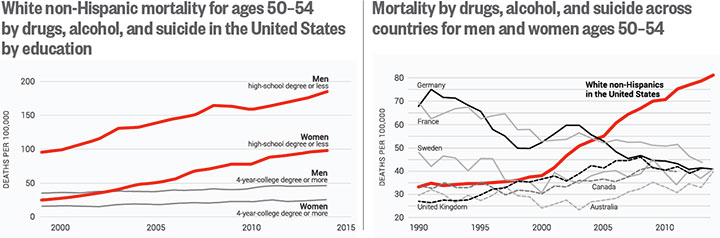

The new paper, “Mortality and Morbidity in the 21st Century,” concludes that among white Americans with a high-school diploma or less, the growth of overall death rates “continued unabated” through 2015, including increases in what they call “deaths of despair” — drug overdoses, suicides, and liver ailments linked to alcoholism.

They found that in 1999, the mortality rate for white non-Hispanics between the ages of 50 and 54 with a high-school diploma or less was 30 percent below the rate it was for 50-54-year-old black non-Hispanics averaged over all education levels. By 2015, that pattern had reversed, with whites having a mortality rate 30 percent higher.

Rising mortality rates were not evident among Americans with undergraduate degrees or higher, nor was it seen in Europe. In this regard, the United States has “left the herd of other rich countries,” Case said in an interview.

Mortality Rates Spike Among White Working-Class Americans

After a century of improved mortality for whites in America, “deaths of despair” — by drugs, alcohol, or suicide — are now on the rise among white non-Hispanics without a college degree

Deaton (now emeritus), who has made a specialty out of studying the seemingly lockstep rise of wealth and well-being throughout history, said that he had been “floored” by the conclusions he and Case reached in their original research. “It was like waking up one morning and there’s no oxygen in the air — it was something that just doesn’t happen,” he said.

When Case and Deaton presented the idea to other academics, it got the same reaction. “People’s jaws would drop,” Deaton said. Even so, they initially had a hard time placing their findings in an academic journal. In 2015, it was quickly rejected by the Journal of the American Medical Association and the New England Journal of Medicine.

After they finally published their results in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in November 2015, the idea caught fire. One reason may have been that Deaton had been named a Nobel laureate a few weeks earlier. But the bigger factor was that the notion of a troubled white working class dovetailed with themes articulated during the nascent 2016 presidential campaign.

The election season was important in vaulting their ideas to the forefront, Case said. In 2016, white working-class voters turned to Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, seeing the mainstream Democratic and Republican parties as unresponsive to their interests. “That was a hook for a lot of reporters, and every candidate discussed it,” Case said. Politico, the ultimate inside-the-Beltway publication, named the Princeton professors to its list of the top 50 “thinkers, doers, and visionaries transforming American politics.”

In March, Case and Deaton presented their new paper at the Brookings Institution. Other scholars praised their findings.

“This is among the most important economic and social findings of the past decade,” said Harvard University economist David Cutler, who has helped Case and Deaton refine their research. “A large segment of the American population is falling behind. ... This is absolutely first-order important and must drive policy discussion.”

Janice Eberly, a finance professor at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, agreed. “The differences in mortality and especially ‘deaths of despair’ across groups should affect us all and how we think about employment, health care, and well-being,” said Eberly, who has also reviewed their work.

Case and Deaton propose a “preliminary but plausible” explanation for the mortality trends: a long-term, “cumulative disadvantage” in the labor market, in marriage, and in health for whites without a college degree.

“We are open to being wrong about this,” Case said. But the hypothesis makes sense, she said. “Your ability to get married goes down if you can’t get a good job. So does your ability to form stable relationships,” she said.

The one specific policy recommendation Deaton and Case make is to curb the “over-prescription” of opioids. “As someone who suffers from chronic pain, I can say that the medical community still does not have a full understanding about the relationship between mind and body,” Case said.

In addition, Case and Deaton urged additional resources for mental health and addiction counseling. In the longer term, Case said, the country needs to come up with a way to provide better vocational and technical education for students who are not headed for college.

Case said she and Deaton have received many emails providing real-life examples of their findings. In one, a 53-year-old woman recalled being at a dinner party and joking that her retirement plan was to be a greeter at Walmart until the day she died. “No one laughed,” Case said. “They all thought they would be greeters at Walmart.”

Case also learned from the emails that people truly dread becoming a burden on others. “So the only way out that they see is by killing themselves,” she said. “That’s a horrible place to be.

WATCH Case and Deaton discuss their research on “deaths of despair”

Courtesy the Brookings Institution

2 Responses

Richard Waugaman ’70

8 Years AgoConsidering our horrendous...

Considering our horrendous and growing plague of income inequality, I was surprised and disappointed that this pivotal study "was quickly rejected by the Journal of the American Medical Association and the New England Journal of Medicine."

I worry that one reason is the power of Big Pharma as purchasers of ads in medical journals. It hurts Big Pharma's bottom line if physicians prescribe fewer opioids. Especially if their previous customers are dying of opioid overdoses.

There's another possible reason their paper was rejected: It was based on innovative observations. Paradoxically, scientists and peer reviewers sometimes feel more comfortable with small extensions of previous knowledge, and don't quite know what to do with truly ground-breaking research. Yes, that's the very research we most need.

Groupthink helps explain this paradox. Without realizing it, experts have a confirmation bias that reinforces what they already know, and makes it difficult for truly new ideas to get heard.

stevewolock

8 Years AgoFor the Record

A research paper by economists Anne Case *88 and Angus Deaton found that in 1999, the mortality rate for white non-Hispanics aged 50–54 with a high-school diploma or less education was 30 percent below the rate for black non-Hispanics of the same age group averaged over all education levels. By 2015, the research paper found, the pattern had reversed. An April 26 Life of the Mind story incorrectly described one of the groups being compared.