Economics: Scandinavia Offers Wage-Gap Insights

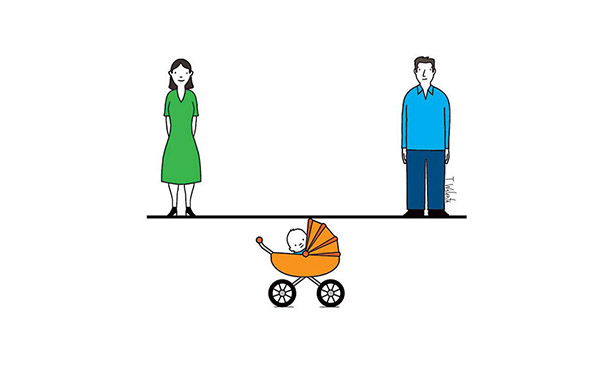

Studying women’s income before and after the birth of their first child, they found that while Danish women’s wages do rebound slightly over time, they still level out about 20 percent below that of men, whose income stays the same before and after children. That difference accounts for nearly the entire wage gap between men and women.

Kleven and his colleagues posit that by bearing the brunt of child care, women tend to make more sacrifices in their careers than their male partners to maintain a flexible work life. Their data show that mothers tend to take jobs that pay less, require fewer hours, and in some cases leave the workforce altogether. Furthermore, they found that even when women stay in high-paid occupations, they are less likely to rise to managerial positions. Kleven speculates that all of these disparities are due to women choosing to maintain a more flexible work life in order to care for children.

Women are essentially trading off family amenities for pay, he says. “In order to make it to the top of the labor market, you need to have a lot of face time with colleagues and managers and be extremely flexible in your ability to travel. Those things are hard when you have kids.” Kleven believes leave policies and subsidies for child care are not enough. “They must be combined with a shift in social norms toward men bearing more of the load of childrearing.”

No responses yet