Essay: The Big Scoop

Throughout the next year, PAW will publish occasional articles and archival items about coeducation in our print issue and social-media accounts. In this essay, Robert K. Durkee ’69 — now Princeton’s vice president and secretary but once an intrepid Daily Princetonian reporter — recalls that momentous time.

Under the circumstances, I was pleased to discover that there seemed to be some interest among the University’s senior leadership in at least thinking about whether Princeton should admit women undergraduates. There was also discussion among students, but other issues got more attention (for example, how late women could stay in the dorms), and student views about coeducation seemed mixed. Some students were in favor, some opposed, but most were prepared to accept that it was not going to happen, and certainly not during our time on campus.

The question was more background noise than front-burner conversation, until a May Wednesday in 1967 when the topic unexpectedly moved to center stage.

During my sophomore year, I was the Prince reporter who covered Nassau Hall. I followed a practice of scheduling an appointment every few months with President Robert Goheen ’40 *48.

My last such appointment of the year was on Thursday, May 11. That day I had a breaking-news item to discuss: I wanted to know if he was planning to attend a speech on campus that night by Alabama Gov. George Wallace. President Goheen eloquently defended the right of a speaker to speak and be heard, as well as the right of others to engage in peaceful protest and dissent, but then said that because of prior commitments he was not planning to attend. I dutifully reported that the next morning.

My notes from that interview show that the Wallace speech was the third of my three topics for that day. I began the interview by asking President Goheen how he felt the University was doing in its efforts to increase the number of black students at Princeton and how he felt about their experiences on campus. The quotes from that part of the interview appeared in an article that was published in the Prince the following fall.

It was the second topic of that interview that ignited campus and even national discussion. I knew that President Goheen’s thinking about undergraduate coeducation had been evolving, and that the trustees were coming to town in June. What was he going to say to them?

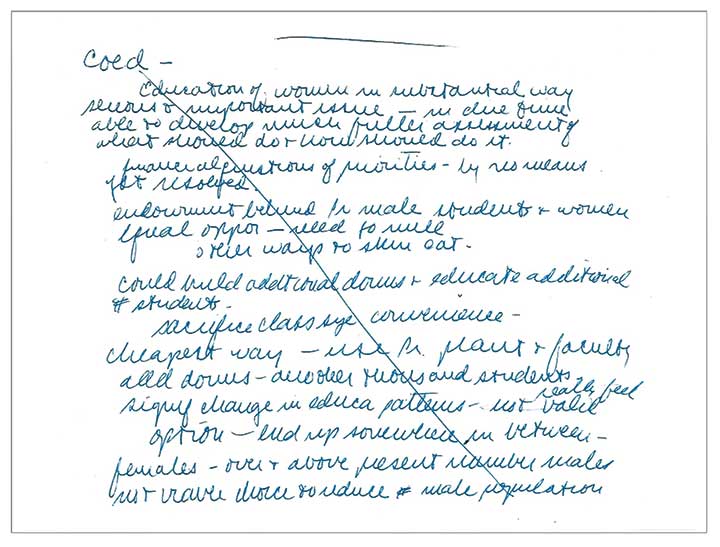

Fortunately, my handwriting then was better than it is now, so my notes from that interview are legible, or at least decipherable. They show that he began by saying that the education of women in a substantial way was a serious and important issue. And then he said “it is inevitable that, at some point in the future, Princeton is going to move into the education of women.” The only questions, he said, were those of strategy, priority, and timing.

The prime reason for adopting coeducation, he said, “won’t and shouldn’t be that Princeton’s social life is warped. This is certainly one consideration, but a greater consideration is what Princeton could offer to women in higher educational opportunity and what women could bring to the intellectual and entire life of Princeton.”

He said there had been preliminary discussion with the trustees and that he was planning for a full discussion in June “with some degree of urgency.” He said he wanted to be sure there would be adequate resources to do things well. The questions of timing and strategy included whether to aim for 1,000 to 1,200 “ladies” in residence in five years (what he called a “crash effort”), or to expand much more slowly by taking over local boarding houses and gradually expanding over a 10-year period.

Either way, he said, Princeton would go into coeducation without reducing the number of male students.

He seemed to be leaning more toward “coordinate education,” a model under which a separate women’s college might be persuaded to take up residence on the University’s lands just across Lake Carnegie (along the lines of discussion taking place at Yale about a merger with Vassar), but he acknowledged that campus sentiment was moving toward full coeducation.We were in reading period, so it was not until the following Wednesday that an article appeared under the headline “Goheen: ‘Coeducation Is Inevitable.’” In addition to igniting campus and national discussion, by all accounts the article set off a bit of a firestorm in Nassau Hall.

Some have suggested that President Goheen was surprised by the story — that he thought our conversation was “off the record.” This would be surprising, since none of our conversations all year had been, and clearly one of the topics (the Wallace speech) involved breaking news. Some suggested he thought the Prince had finished publishing for the year, but the paper always published through reading period (not always to the academic advantage of its reporters and editors!).

It is possible that he had become comfortable with our periodic conversations and said more than he intended to say. But it is also possible that he made a strategic decision to do exactly what he did. He knew he faced an uphill battle to persuade the trustees to authorize a serious assessment of coeducation. And surely he knew that if there was awareness on campus that he was bringing this question to the trustees, and if there was evidence of strong and growing campus interest in coeducation, it would be less likely that the trustees would respond to his request for a study with a denial, or a plea for more time before agreeing to consider the issue.

What happened at the June meeting was that the trustees did agree to a comprehensive study of the desirability and feasibility of undergraduate coeducation. A year later, the trustees received an interim report from a committee chaired by economics professor Gardner Patterson that recommended having 1,000 to 1,200 women on campus within the next decade. In January 1969, the trustees had what I described in a Prince article as their “rendezvous with inevitability.” On Jan. 11, the trustees voted “in principle” to approve the recommendations of the Patterson report and committed Princeton to becoming coeducational, but approved no specific plan and set no date.

Following that trustee vote, I wrote my last Prince article about coeducation, saying that “after 18 months of study, survey and soul-searching,” the trustees had encountered the inevitability of coeducation by adopting a new principle — “but no girls.” But my headline said “Coeds could attend Princeton in ’69,” and I suggested that the administration was likely to bring a recommendation for implementation to the April trustee meeting. “With a little luck,” I wrote, there could be “a significant number of girls — not just a token sampling” on campus next fall. Otherwise, I suggested, Princeton would lose a year in the admission race with Yale and would probably face “vigorous student dissatisfaction.”

The final sentence of that article said, “Before next year’s freshmen graduate, there will very probably be 1,000 girls on campus.” At their April 1969 meeting, the trustees did, in fact, vote to admit women undergraduates beginning that fall, and four years later there were, indeed, 1,000 women undergraduates on campus.

In admitting women undergraduates in the fall of 1969, the University decided that women who had studied on campus in 1968–1969 under the Critical Languages Program — created in 1963 so that visiting students could study languages such as Chinese, Japanese, Russian, and Arabic at Princeton — would be permitted to remain an additional year. Nine of these women would receive a Princeton degree in the Class of 1970, making them Princeton’s first undergraduate alumnae. They were among the 101 female first-year students and 70 female transfer students who pioneered undergraduate coeducation at Princeton in September 1969, barely three months after my classmates and I had graduated.

No responses yet