Essay: Hard fall, hard lesson

“Harley? You’re first!”

The announcer’s words crackle over a loudspeaker in my direction, but not at me — he’s talking to the horse I’m sitting on. I have known Harley for only five minutes, but now we are a team, bonded by mutual fear. Harley seems skittish about the inexperienced rider on his back, and I’m afraid that I’ve made a big mistake: I have entered the weekly rodeo at a guest ranch in Wyoming.

The first event is barrel racing, known as a “girl’s event” on the pro rodeo circuit, but one that requires experience, adroit handling, and intimate knowledge of horses — none of which I possess.

It is too late to back out. My son, daughter, and granddaughter are all mounted up behind me, their horses whinnying and pawing the ground. My wife and the rest of my family are watching from the bleachers. I find myself thinking about the old TV Westerns I used to watch as a kid — The Roy Rogers Show, The Lone Ranger, Maverick, Bonanza. Maybe I can blame them. They all romanticized an Old West that never existed. Now, as the oldest rodeo competitor here by at least 20 years, I am trapped in a reptile-memory, baby-boomer fantasy.

A barrel-racing course looks deceptively simple. It’s laid out like a baseball diamond. You and your horse begin at home plate, go to the barrel on first base and turn around it, cross and circle third base, head out to second, and then dash straight back home. You circle the first barrel on the right and then two lefts — all against the stopwatch. The pros make it look easy, using their legs, not their hands and arms, to guide specially trained horses. Their literature abounds in Zen-like maxims (“Create Soft, Round Movement for Sharp Turns and Fast Runs,” says one website).

Harley and I, barely introduced but, I hope, as familiar as an old vaudeville team, are soon at the starting line, a chalky scratch in the dust. “Go when you’re ready,” the announcer says. And suddenly we are trotting and loping awkwardly to the first barrel. We navigate it and then pick up speed over to the next one. This is easy! We head down to the last barrel, circle it tightly, and now all we have to do is canter straight to home for the roses and glory.

And therein lies my undoing. As Harley shifts gears from a trot to a lope, I pull off my white cowboy hat and wave it at the crowd in the bleachers. Suddenly I have become the Marlboro Man, giving the sequined teenage cowgirls a wave — nothin’ too fancy — as I ride manfully into the sunset.

What I do not know is that horses see themselves as potential prey in a world red in tooth and claw. Their best defense is their speed. They run. So when a mysterious white object suddenly flutters into the corner of their vision, they panic.

Harley spooks, wild-eyed, suddenly galloping ahead and leaping to his left. I go airborne, watching with fascination as the horse slides out from under my legs. I hang for a moment in the air, suspended in slow-motion like one of those Warner Bros. cartoon characters who goes off a cliff, his legs pinwheeling.

Then, astonishingly, the Earth rises up and smites me. I have landed flat on my back — fortunately, as it turns out, since in the overwhelming majority of the worst horseback accidents, riders land on their heads or necks, often with catastrophic results. The morbidity and mortality rate among horse riders is 20 times higher than that of motorcyclists.

I sit in the dust, stunned. Wranglers and officials run over to me. DontmoveLiedown. Canyoufeelyourlegs? Areyounumb? I mumble a few responses; then, as I have learned to do from watching TV timeouts for injured football players, I give a thumbs-up, dust myself off, and limp away. The crowd claps politely for a fellow who has done nothing but fall off a horse.

A visit to a hospital emergency room the next day reveals three broken vertebrae. Again, I was lucky. The bruise on my back is the size and shape of South America, but I should be healed in six weeks. The worse wound is to my pride. I am no Tom Mix. I am not even Gabby Hayes. I am an age-denying, pre-baby boomer whose reach exceeds his grasp.

In the car later, my daughter tries to console me by saying that occasional disappointment is the price for being ambitious. My 6-year-old grandson finds another lesson. When I ask him what he has learned from this episode, he looks at me very carefully and says, “Never show off on a horse.”

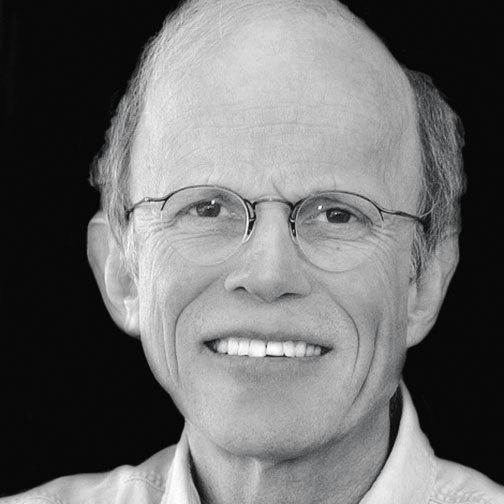

Landon Y. Jones ’66 is the former managing editor of People and Money magazines, a former editor of PAW, and the author of Great Expectations: America and the Baby Boom Generation. This essay originally appeared in The Wall Street Journal.

No responses yet