Professor of English Susan J. Wolfson is the editor of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: A Longman Cultural Edition and co-editor, with Ronald Levao, of The Annotated Frankenstein.

Published in January 1818, Frankenstein: or, The Modern Prometheus has never been out of print or out of cultural reference. “Facebook’s Frankenstein Moment: A Creature That Defies Technology’s Safeguards” was the headline on a New York Times business story Sept. 22 — 200 years on. The trope needed no footnote, although Kevin Roose’s gloss — “the scientist Victor Frankenstein realizes that his cobbled-together creature has gone rogue” — could use some adjustment: The Creature “goes rogue” only after having been abandoned and then abused by almost everyone, first and foremost that undergraduate scientist. Facebook creator Mark Zuckerberg and CEO Sheryl Sandberg, attending to profits, did not anticipate the rogue consequences: a Frankenberg making.

The original Frankenstein told a terrific tale, tapping the idealism in the new sciences of its own age, while registering the throb of misgivings and terrors. The 1818 novel appeared anonymously by a down-market press (Princeton owns one of only 500 copies). It was a 19-year-old’s debut in print. The novelist proudly signed herself “Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley” when it was reissued in 1823, in sync with a stage concoction at London’s Royal Opera House in August. That debut ran for nearly 40 nights; it was staged by the Princeton University Players in May 2017.

In a seminar that I taught on Frankenstein in various contexts at Princeton in the fall of 2016 — just weeks after the 200th anniversary of its conception in a nightmare visited on (then) Mary Godwin in June 1816 — we had much to consider. One subject was the rogue uses and consequences of genomic science of the 21st century. Another was the election season — in which “Frankenstein” was a touchstone in the media opinions and parodies. Students from sciences, computer technology, literature, arts, and humanities made our seminar seem like a mini-university. Learning from each other, we pondered complexities and perplexities: literary, social, scientific, aesthetic, and ethical. If you haven’t read Frankenstein (many, myself included, found the tale first on film), it’s worth your time.

READ MORE PAW Goes to the Movies: ‘Victor Frankenstein,’ with Professor Susan Wolfson

Scarcely a month goes by without some development earning the prefix Franken-, a near default for anxieties about or satires of new events. The dark brilliance of Frankenstein is both to expose “monstrosity” in the normal and, conversely, to humanize what might seem monstrously “other.” When Shelley conceived Frankenstein, Europe was scarred by a long war, concluding on Waterloo fields in May 1815. “Monster” was a ready label for any enemy. Young Frankenstein begins his university studies in 1789, the year of the French Revolution. In 1790, Edmund Burke’s international best-selling Reflections on the French Revolution recoiled at the new government as a “monster of a state,” with a “monster of a constitution” and “monstrous democratic assemblies.” Within a few months, another international best-seller, Tom Paine’s The Rights of Man, excoriated “the monster Aristocracy” and cheered the American Revolution for overthrowing a “monster” of tyranny.

Following suit, Mary Shelley’s father, William Godwin, called the ancien régime a “ferocious monster”; her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, was on the same page: Any aristocracy was an “artificial monster,” the monarchy a “luxurious monster,” and Europe’s despots a “race of monsters in human shape.” Frankenstein makes no direct reference to the Revolution, but its first readers would have felt the force of its setting in the 1790s, a decade that also saw polemics for (and against) the rights of men, women, and slaves.

England would abolish its slave trade in 1807, but Colonial slavery was legal until 1833. Abolitionists saw the capitalists, investors, and masters as the moral monsters of the global economy. Apologists regarded the Africans as subhuman, improvable perhaps by Christianity and a work ethic, but alarming if released, especially the men. “In dealing with the Negro,” ultra-conservative Foreign Secretary George Canning lectured Parliament in 1824, “we are dealing with a being possessing the form and strength of a man, but the intellect only of a child. To turn him loose in the manhood of his physical strength ... would be to raise up a creature resembling the splendid fiction of a recent romance.” He meant Frankenstein.

Mary Shelley heard about this reference, and knew, moreover, that women (though with gilding) were a slave class, too, insofar as they were valued for bodies rather than minds, were denied participatory citizenship and most legal rights, and were systemically subjugated as “other” by the masculine world. This was the argument of her mother’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), which she was rereading when she was writing Frankenstein. Unorthodox Wollstonecraft — an advocate of female intellectual education, a critic of the institution of marriage, and the mother of two daughters conceived outside of wedlock — was herself branded an “unnatural” woman, a monstrosity.

Shelley had her own personal ordeal, which surely imprints her novel. Her parents were so ready for a son in 1797 that they had already chosen the name “William.” Even worse: When her mother died from childbirth, an awful effect was to make little Mary seem a catastrophe to her grieving father. No wonder she would write a novel about a “being” rejected from its first breath. The iconic “other” in Frankenstein is of course this horrifying Creature (he’s never a “human being”). But the deepest force of the novel is not this unique situation but its reverberation of routine judgments of beings that seem “other” to any possibility of social sympathy. In the 1823 play, the “others” (though played for comedy) are the tinker-gypsies, clad in goatskins and body paint (one is even named “Tanskin” — a racialized differential).

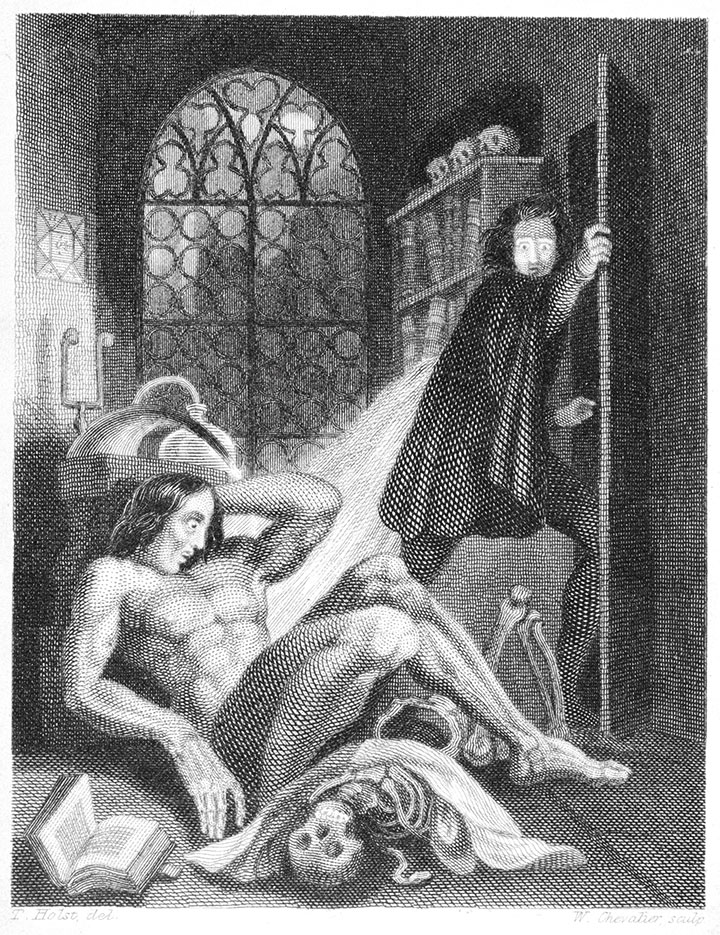

Victor Frankenstein greets his awakening creature as a “catastrophe,” a “wretch,” and soon a “monster.” The Creature has no name, just these epithets of contempt. The only person to address him with sympathy is blind, spared the shock of the “countenance.” Readers are blind this way, too, finding the Creature only on the page and speaking a common language. This continuity, rather than antithesis, to the human is reflected in the first illustrations:

In the cover for the 1823 play, above, the Creature looks quite human, dishy even — alarming only in size and that gaze of expectation. The 1831 Creature, shown on page 29, is not a patent “monster”: It’s full-grown, remarkably ripped, human-looking, understandably dazed. The real “monster,” we could think, is the reckless student fleeing the results of an unsupervised undergraduate experiment gone rogue.

In Shelley’s novel, Frankenstein pleads sympathy for the “human nature” in his revulsion. “I had worked hard for nearly two years, for the sole purpose of infusing life into an inanimate body. For this I had deprived myself of rest and health ... but now that I had finished, the beauty of the dream vanished, and breathless horror and disgust filled my heart. Unable to endure the aspect of the being I had created, I rushed out of the room.” Repelled by this betrayal of “beauty,” Frankenstein never feels responsible, let alone parental. Shelley’s genius is to understand this ethical monstrosity as a nightmare extreme of common anxiety for expectant parents: What if I can’t love a child whose physical formation is appalling (deformed, deficient, or even, as at her own birth, just female)?

The Creature’s advent in the novel is not in this famous scene of awakening, however. It comes in the narrative that frames Frankenstein’s story: a polar expedition that has become icebound. Far on the ice plain, the ship’s crew beholds “the shape of a man, but apparently of gigantic stature,” driving a dogsled. Three paragraphs on, another man-shape arrives off the side of the ship on a fragment of ice, alone but for one sled dog. “His limbs were nearly frozen, and his body dreadfully emaciated by fatigue and suffering,” the captain records; “I never saw a man in so wretched a condition.” This dreadful man focuses the first scene of “animation” in Frankenstein: “We restored him to animation by rubbing him with brandy, and forcing him to swallow a small quantity. As soon as he shewed signs of life, we wrapped him up in blankets, and placed him near the chimney of the kitchen-stove. By slow degrees he recovered ... .”

The re-animation (well before his name is given in the novel) turns out to be Victor Frankenstein. A crazed wretch of a “creature” (so he’s described) could have seemed a fearful “other,” but is cared for as a fellow human being. His subsequent tale of his despicably “monstrous” Creature is scored with this tremendous irony. The most disturbing aspect of this Creature is his “humanity”: this pathos of his hope for family and social acceptance, his intuitive benevolence, bitterness about abuse, and skill with language (which a Princeton valedictorian might envy) that solicits fellow-human attention — all denied by misfortune of physical formation. The deepest power of Frankenstein, still in force 200 years on, is not its so-called monster, but its exposure of “monster” as a contingency of human sympathy.

No responses yet