Sara Evans ’08 is a writer and researcher based in the Southwest.

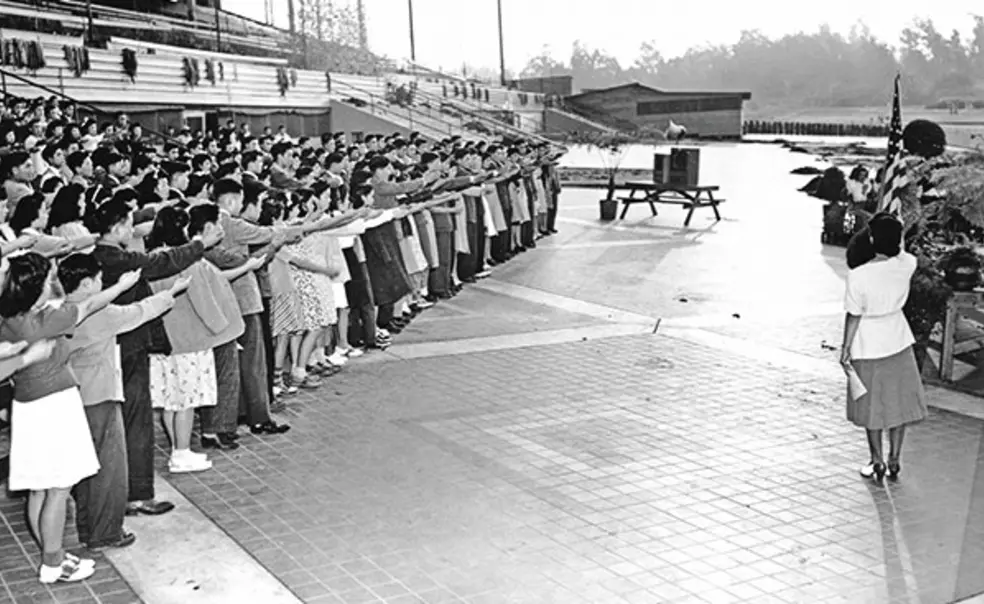

In the last days of 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, drawing America into World War II. Two months later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared that 120,000 Japanese Americans were to be removed from their homes on the West Coast and incarcerated in concentration camps farther inland.

A July 13, 1942, editorial in The Daily Princetonian declared, “America has found a scapegoat.”

The 75th anniversary of the beginning of the internment was recognized last year at events throughout the country. What was not commemorated, and what is not widely known, is the story of several thousand young Japanese Americans who found their education interrupted by eviction from their West Coast homes and who, through the inspired efforts of West Coast educators and philanthropists, were granted a reprieve from their imprisonment in order to continue their studies at colleges and universities from the Midwest to the Eastern Seaboard.

The story of these students, known as “the College Nisei,” intersects with Princeton’s story, if only briefly.

In mid-1942, after much lobbying on the part of university presidents and other educators from Los Angeles to Seattle, the federal government directed that a new quasi-governmental body called the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council be formed and tasked with placing interned students in institutions of higher education outside the exclusion area.

The government’s decision to allow thousands of internees to leave the camps when it had just gone to the trouble of locking them up might seem absurd, but it was just one manifestation of the schizophrenia that was characteristic of internment policy throughout the war. For example, one of the primary reasons the government gave for incarcerating Japanese Americans through 1945 was the possibility of military sabotage. However, by the end of the war, Japanese Americans had been serving honorably in the military for two years either as volunteers or as draftees from the camps. Still others had been involved in sensitive intelligence work for a similar length of time.

In its early days, the council sent letters to hundreds of universities asking if they would be willing to enroll the displaced students. This small act placed the Japanese American question squarely on the doorstep of each institution; each college president had to choose whether to compound the burden of incarceration or to show “respect and love for democracy ... regardless of abstract or concrete justifications [for the internment] which may exist in the public mind.”

In the summer of 1942, as news of the student relocation spread, the Prince editorial board issued its July 13 condemnation of the internment. In a bold but not inaccurate rhetorical flourish, the Prince lamented that “the political machinations of democracy entomb loyal Americans and much-needed scholars and linguists in the bleak wastelands of Southern California,” and urged Princeton administrators to “give careful consideration” to the possibility of enrolling displaced students.

In fact, University President Harold Dodds *1914 had already sent Princeton’s reply to the council.

In a July 2, 1942, letter to council director Robbins Barstow, Dodds expressed Princeton’s refusal to accept “evacuated Japanese American citizens” on the grounds that “few if any of the students concerned could transfer to Princeton” as they were not “qualified” to cope with the intellectual rigors of a “closely knit and highly articulated” undergraduate curriculum.

The process by which the University reached its decision is unclear; there are no explanatory notes in Princeton’s archives and no mention of the issue in official documents. Since the letter came from Dodds’ desk, it must be assumed that the decision was largely his.

Ultimately, it appears from the surviving documents that no interned Japanese American matriculated at Princeton as a full-time undergraduate or graduate student during the war.

In a July 7 reply to Dodds, Barstow speculated that Dodds would “be interested to know” that a number of “well qualified” high school graduates also were eager to apply to Princeton, though he acknowledged that “it may be unwise for other reasons to place Japanese [American] students in Princeton,” signaling that he had received the message Dodds had written between the lines: Japanese Americans were not welcome at Old Nassau at that time.

Though there were various later attempts by faculty members and administrators outside the president’s office to place interned Japanese Americans as new undergraduate and graduate students at Princeton (avoiding Dodds’ ban on transfers), all of these placements ultimately failed. Reasons were varied: Princeton had not been cleared by the War Relocation Authority in time for a given student’s matriculation; there were purportedly not enough teaching staff available in a student’s chosen area of study; or a prospective student’s draft status changed and he was required by the University to defer his matriculation.

According to available evidence, the University’s later attempts to enroll Japanese American internees were good-faith efforts to abide by the letter of Dodds’ decision while tacitly rejecting its spirit. But ultimately, it appears from the surviving documents that no interned Japanese American matriculated at Princeton as a full-time undergraduate or graduate student during the war.

Other colleges and universities were mixed in their responses to the council’s overture. Acceptance of Japanese American students depended largely on the personal views of a school’s leadership and on the degree of racism in the surrounding community. Some placements were highly successful. Elsewhere, local residents formed lynch mobs, in their mouths the doctrine of racial determinism that gave rise to the internment — namely, that blood dictated loyalty — and in their hearts simple racial hatred.

The council’s surviving records indicate that the Ivy League was divided. Columbia welcomed displaced students even before it had been cleared by the government to do so; Yale accepted several students, including some of those unable to attend Princeton; and Harvard and Brown also enrolled internees. The council’s records suggest that some students of Japanese ethnicity attended Cornell and Dartmouth, though it is unclear if these students were American or Japanese nationals, and if Americans, whether they were internees. The University of Pennsylvania attempted to obstruct Japanese American enrollment early in the war but was eventually defeated by bad press.

The last 75 years have brought radical and welcome sociopolitical change to American life, rendering the universities of today very different from the ones that educated the Greatest Generation.

Princeton is no exception. It is inspiring to trace the seismic changes that have taken place since the war years in the people, programs, and ethos that make up the University, and to reflect that this progress is the foundation of greater things to come.

The little-told story of the College Nisei, accordingly, ends in a kind of redemption.

Many of the internees have passed away, but not before earning their college degrees and imparting to their children and grandchildren a sense of the value of that endeavor. These third- and fourth-generation Americans have grown up and found their own places in national and international life. Some have even attended and graduated from the very same universities that rejected their relatives more than 75 years ago.

Justice deferred? Certainly. But not forever denied.

1 Response

James C. Neely ’48

8 Years AgoContext for an Injustice

Seldom mentioned is the West Coast terror that prompted the World War II evacuation you write about (“How an Injustice Touched Princeton,” On the Campus, Jan. 10), but you should be apprised of some of the facts that surround that time. At the time of Pearl Harbor the West Coast was cordoned off from Seattle to Los Angeles by a cordon of 19 Japanese submarines at regular intervals. On Christmas Eve 1941, Japanese sub I-15 surfaced offshore of San Francisco Bay with orders to fire on the city. Balloons released from subs landed on Oregon picnickers, killing two people, and a gasoline refinery in Santa Barbara was fired upon and set ablaze. Rumors were rife that the Japanese consulate in Hawaii had housed spies notifying Japan of Pearl Harbor shipping postures. That same conspiracy was feared for San Francisco – totally unprepared, an invasion was anticipated. None of this in retrospect can justify what was done, but it lends some understanding. It was the Midwestern colleges like Washington University in St. Louis, for obvious reasons, that generously accepted displaced students at this time.