Ex-Princeton fellow’s tale triggers postdoc debate among grad students

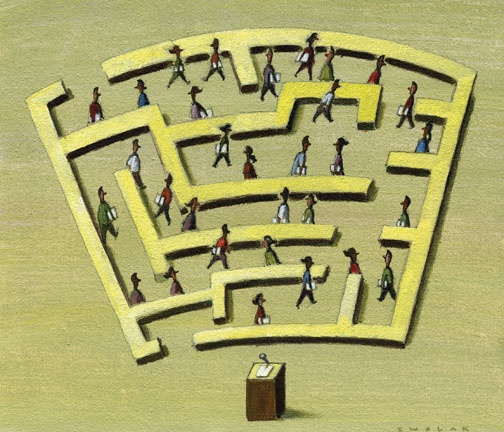

A former Princeton postdoc has sparked a soul-searching conversation among Ph.D. students with a blog post that criticizes the intensifying rat race for tenure-track faculty positions.

Ethan Perlstein, an evolutionary pharmacologist and until recently a Lewis-Sigler Fellow at the University, once clung to the dream of becoming a tenured professor, jumping through academic hoops and deferring the start of a family to make it a reality. But as he neared the end of his fellowship without an enticing college job offer, he decided he could not put his life on hold any longer with another postdoc position.

Perlstein now thinks he was naïve to believe he could sail into a tenured professorship simply by checking all of the academic boxes needed and apprenticing as a postdoc at top-tier universities.

“My ‘postdocalypse now’ post is a cautionary tale of expectations versus reality that I think is common among a lot of academic trainees,” Perlstein said, referring to his provocatively titled blog post that laments the increasing obstacles for life-science students in the chase for tenure.

Sarah Grady, a fourth-year Princeton Ph.D. student in molecular biology, also flirted with the idea of becoming a professor before ultimately realizing the tenure-track rigmarole was not for her. “I’ve seen countless friends and lab members go through the process of finding a postdoc, finding another postdoc, publishing as much as possible in a short time, and competing with hundreds of others for a single faculty position,” she said.

“While I agree that academic postdocs can be a worthwhile experience for some, the combination of low pay, long hours, and little opportunity for professorships makes the rarefied air at a major university a little more difficult to breathe,” Grady added.

Amir Roknabadi, a third-year Princeton Ph.D. student in molecular biology from Iran, has read Perlstein’s post and knows that he faces long odds. But Roknabadi can’t shake the dream of becoming a professor, which he believes would afford him the freedom to pursue his intellectual passions as no other job can. Nevertheless, he looks down the road with some trepidation.

“There are too many Ph.D.s,” Roknabadi said, and standing out in such a large group of impressive candidates requires not only hard work, noteworthy publications, and brilliance — but also plenty of luck.

A 2012 survey by the American Association for the Advancement of Science found that 56 percent of postdocs said they expected to get tenure-track spots, but only 21 percent ended up with one.

“The market is clearly not functioning properly because it seems to be more of a lottery, as opposed to a meritocracy,” Perlstein said. “At the point where you’ve reached an assistant-professor search, you’ve got people who survived college, graduate school, and a postdoc — and sometimes multiple postdocs.”

In the 2011–12 academic year, 53 percent of Princeton Ph.D. students in the natural sciences went on to become postdocs, according to University statistics. The figures were lower for other disciplines: 23 percent of doctoral-degree recipients in the social sciences, 15 percent of those in the humanities, and 24 percent of those in engineering reported taking postdoc positions.

Daniel Wright, a fourth-year Ph.D. student in environmental engineering who once yearned to become a professor, now is looking outside of academia. “You have the opportunity to get involved in bigger sorts of projects, potentially projects that involve many different people across many different disciplines,” he said. “When I realized that, the other stuff just fell away.”

That echoes the new attitude of Perlstein, who said he can have just as big an impact outside of academia, particularly by blogging and tweeting his ideas. “As I progressed toward a Ph.D., being a scientist meant being an academic,” he said. “Now I see that science is a calling, but ‘professor’ is just a job title.”

2 Responses

Dan Fineman *76

10 Years AgoPh.Ds, postdocs, and careers

While the catalyst for this article came from a scientist, I do not know why the article only investigates that angle in a magazine devoted to the whole institution. Are the circumstances better or worse in the humanities, arts, and social sciences? I have reason to believe they are worse. Three-quarters of all post-secondary teachers are now contingent: teaching for minimal wages and without security or benefits. At the same time, educational debt has become unmanageable.

Still, Princeton has an incoming president who says of Coursera — whose contracts exclude faculty from direct negotiation — that MOOCs “may be able to help change the cost curve at institutions that are facing a lot of pressure.” This needs little translation: That online system will place additional downward pressure on doctorate jobs. Education is facing many crises that threaten to make the enterprise unsuccessful. Where is Princeton’s holistic meditation on these problems?

Jim Gilland *88

10 Years AgoPh.Ds, postdocs, and careers

The fact that there are postdocs (On the Campus, April 24) shows a failure of the Ph.D. educational system. The Ph.D. is supposed to be enough preparation for starting an academic career. The postdoc’s sheer existence indicates an unbalanced supply and demand (as many observed in the article).

The American Physical Society ran a guest essay in its newsletter several years ago in which a graduate student reveled in his seemingly unique realization that not everyone with a Ph.D. in physics would go on to teach. Apparently, his professors and department were saying or implying otherwise. The APS also ran numerous articles advising physics students to go into engineering, in light of academe’s situation. Never mind the fact that they then were competing with engineers trained in the field the physicists came to late.

The argument that the United States needs more STEM education apparently doesn’t stem (sorry) from a need for advanced degrees, but for workers who can understand the math and science to do skilled manufacturing in aerospace and the like. But it’s being used to sell more graduating Ph.D.s who have nowhere to teach.