F. Scott Fitzgerald’s First Love

Before Scott marries Zelda, he was smitten by a young debutante who became the model for Gatsby’s Daisy

Among the lists that F. Scott Fitzgerald ’17 constantly was making and remaking was one in which he recorded his “feminine fixations,” according to his final companion, Sheila Graham. There were 16 women in all, beginning with Marie Hersey, an innocent crush from his youth in St. Paul, Minnesota, and ending with Graham herself, in whose arms he died, in 1940. Fitzgerald’s wife, Zelda Sayre, made the list, of course, and so did Ginevra King, the celebrated Chicago debutante who was Fitzgerald’s first love and Zelda’s only real rival as a major influence on his writing. Fitzgerald was so smitten by King that for years he could not think of her without tears coming to his eyes.

“He had invested a good deal of his feeling for the promises of life in her,” explained Fitzgerald biographer Arthur Mizener in The Far Side of Paradise, “and for Fitzgerald that kind of investment was always final.”

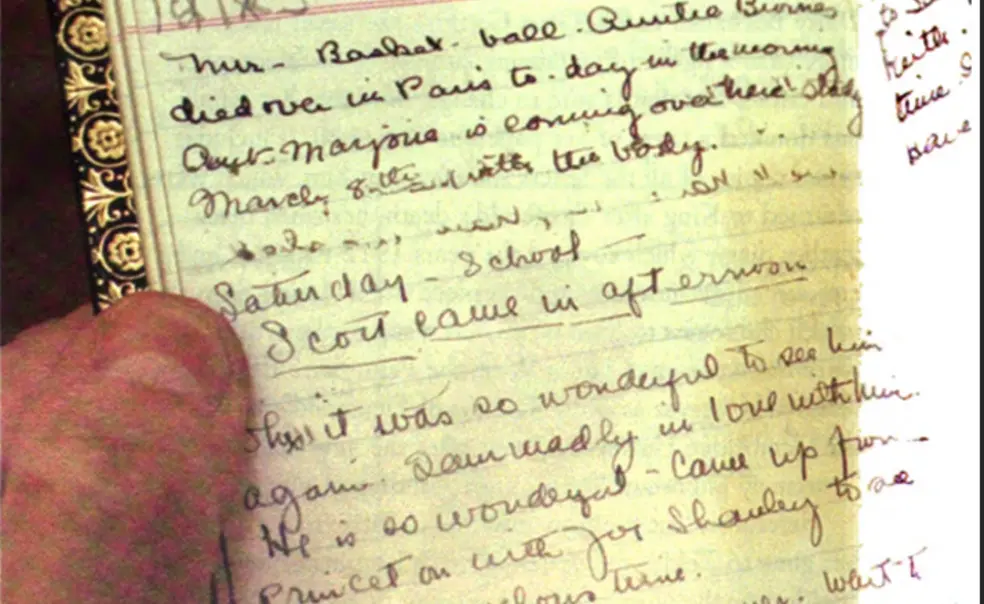

King died in 1980, at 82. As important as she was to Fitzgerald – the model for characters such as Isabelle in “Babes in the Woods,” which he wrote for the Nassau Lit in 1917 and in which he gave an unadorned account of their meeting; Judy Jones in “Winter Dreams,” Josephine Perry in the four Josephine stories, and, most significantly, Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby – she never has been more than a figure of tantalizing surmise to his biographers and critics. But that is sure to change, now that her family has donated a trove of her papers to Princeton. It includes typed copies of all the letters she ever sent him, which were returned to King after Fitzgerald’s death; her small black leather diary, which covered the years 1912 to 1915; and a curious 1950s autobiographical piece titled “Love? Story,” which she seems to have written as a sop to the writers who were nosing around. James West, the Penn State English professor who serves as a general editor of Fitzgerald’s works for the Cambridge University Press, rates the new material as “extremely important” to our understanding of Fitzgerald.

“Heretofore, most of the attention in Fitzgerald studies has gone to Zelda, and certainly that’s legitimate,” says West. “Zelda was the most important woman in his life. But Ginerva was extremely important to his writing. He based character after character on her through his career, and yet we’ve known almost nothing of her. She was elusive with Fitzgerald’s two biographers and after that didn’t talk to anyone else. For Zelda we have a great amount of information. For Ginevra, we’ve had virtually nothing.”

Alas, one thing we will never have is Fitzgerald’s side of the correspondence; he had asked King to get rid of it. “I have destroyed your letters – so you needn’t be afraid that they will be held up as incriminating evidence,” she teases in one of her last letters, on July 17, 1917. “They were harmless – have you a guilty conscience?”

If he did not have one then, he ought to have developed one later on. Not only did Fitzgerald not honor King’s polite request that he destroy her letters, he actually had them typed up, probably around 1930, in order to “hear” her voice better as he prepared to write the four “Josephine stories.” He wanted to work from a typed copy partly to spare his eyes the trouble of deciphering her small, cramped handwriting, but also, West theorized, to spare himself the emotional trauma he knew they might produce. “Having them typed,” West says, “allowed him to objectify the letter in a way that he couldn’t have done if he’d held the actual letters in a way that he couldn’t have done if he’d held the actual letters that she’d held and written.”

The pair first met January 1, 1915, when King took the train from her home in Lake Forest, Illinois, to St. Paul to visit Marie Hersey, her roommate at Westover, a girls’ school in Middlebury Connecticut. She was 16, he 18. The attraction was quick, strong, and mutual. “Am absolutely gone on Scott!” she records the day after they first met. “He left for Princeton at 11: – oh – ! –“

For the next five months they corresponded feverishly, even competitively, some days scrawling as many as 24 pages. To find time for this outpouring, she often skipped Bible class. On January 23 she notes in her diary, “Letter from Albius and wonderful one from Scott (he is so darling).” Using a florid system of punctuation, virtually every mention of his name gets an exclamation point, dashes, or underlining.

King’s voice virtually skips across the pages, by turns flirtatious, coy and worldly, full of schoolgirl hyperbole and breathless longing. “Oh Scott why aren’t we…somewhere else to-night?” she laments. “Why aren’t we at a dance in summer now with a full moon a big lovely garden and soft music in the distance. I don’t want to be here!”

King seems to have been a bright if uninterested student, whose best subject was, by her admission, “letter writing.” She was a talented athlete. “I’m working like a Trojan for the [basketball and tennis] teams,” she reports, and occasionally mentions jogging. Mostly, she is content to be an effortless charmer. A photo of herself arrives with the comment, “Ain’t I just a bear!”

She visited Yale often. Indeed, she later told her daughter of telling Fitzgerald she had to return to Westover only to meet some Yale boys on the other side of Grand Central. “I think she was a little bit of a devil,” chuckles Ginevra King Chandler, one of King’s granddaughters, a lawyer in Ukiah, California. Fitzgerald must have known he had rivals in New Haven, which may explain why Tom Buchanan, brutish and monosyllabic, is made a Yalie.

There is no question that she was a terrible flirt. “I hear you had plans for kissing me goodbye publicly,” she informs him on January 25, 1915. “My goodness, I’m glad you didn’t. I’d have had to be severe as anything with you! (Ans. This – Why didn’t you?)”

More intriguing than her flirting, though, is her ongoing longing for something deeper, a more meaningful life than the one permitted a young woman of her era and social class. “Sometimes I feel oh so tired of dances and flirtations and silly talk and do long to have a long and really serious talk with somebody.” King strikes this note regularly, but never at any length, leaving one to wonder just how eager she really was to have such a conversation.

Fascinating as it is to hear Daisy Buchanan’s original voice, the letters are even more important for letting us make a judgement about the fictional use Fitzgerald made of her. King was, after all, a member of the highest reaches of society, a world from which Fitzgerald himself felt excluded. She was the most glamorous of Chicago’s Big Four debutantes and came from money so old and extensive no one today seems quite sure where it came from. Much as he was intoxicated by this world, Fitzgerald seems early on to have understood its power to corrupt and deaden. In “Winter Dreams,” published in 1920, Judy Jones, the beautiful, icy golfer based on King, seems to be a victim as much as a manipulator.

“I don’t know that Fitzgerald ever captured the real Ginevra in his fiction,” says West, “but then he wasn’t really trying to. Rather, he was creating a character – by beginning with the young girl he had known but amplifying her personality, giving it flaws, and letting his imagination play over the possibilities for the woman she might become.”

In most every way, the real Ginevra seems “better” – smarter, more open-minded, less grasping – than her fictional offspring. “She was an open, direct young woman,” says West. “I like her very much.”

West reckons they were seldom, if ever, alone together. Begging him to find a chaperone, she counsels “a dumb and blind one is best.” Musing on their frustrations leads to the most intriguing single thread in their correspondence: their ongoing discussion of what they might do if they could spend one hour together. What would they do in that single “Perfect Hour?” King first uses the phrase on February 15, 1915, apparently responding to something he’s written: “Someday – Scott – some day. Perhaps in a year – two – three – We’ll have that perfect hour! I want it – and so we’ll have it!” Her yearning surely finds an echo at the end of The Great Gatsby: “…tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther….And one fine morning –”

For months, Fitzgerald and King bat the notion back and forth until finally, 13 months later, she announces, “Enclosed you’ll find out my idea of a “Perfect hour” is [sic]. So you see my idea is quite different from yours. It isn’t a bit clever, so don’t expect anything.”

But it is clever, if in a way Fitzgerald probably was not expecting since it is satire, not romance. It is the story of a young girl, who, on the ever of her wedding to a “titled Russian” named Count Leonardo Spagettioni, decides she must make one last visit to her former flame, a movie producer named Mr. Fitz-Gerald. “Leonardo was good but no, he would not give her what she craved – affection – real deep sympathy …”

The girl visits Fitz-Gerald in his apartment, which is a veritable shrine to Princeton, sporting “tapestries of old Nassau,” andirons “in the form of tigers,” and even a copy of the Nassau Lit. She is heartbroken to learn he has no idea who she is. “Good grief,” he says. “Don’t cry – you’d almost do for new opera – ‘When Tears are Wet’ … Who are you anyhow?” When she tells him she is Ginevra King, he mistakes the name for a toothpaste brand, and must consult a “huge box of files” containing the names of his many conquests. “Let me see,” he says. “Wolcott, Helen – Teale, Robin, Robertson, Fandric …”

“There she saw, vanishing with the last of her beautiful air-castles, the vision of a perfect hour … was fading away like a spent rose,” the story concludes.

No one is going to mistake this for great literature, but it is intriguing for a number of reasons. First, Fitzgerald seems to have lifted from it several details he’d use in The Great Gatsby, including Lohengrin’s “Wedding March.” More important, the idea of going to great lengths to revive an old, true love lies at the very heart of Gatsby.

One wonders if the fact that she felt free to lampoon him is a clue that theirs was no longer a romantic relationship. Fitzgerald later would say that King dumped him “with the most supreme boredom and indifference,” but the letters don’t support that. It’s hard, if not ultimately impossible, to tell the true death of her feelings for Fitzgerald. Many years later, King would dismiss the relationship lightly, as a “silly passing romance,” adding, “There were a lot of boys back then.” Still, she and Fitzgerald continued to correspond until the summer of 1917, though less regularly and a lot less breathlessly. Perhaps, suggests West, “she had seen him against the backdrop of Lake Forest by that time, as opposed to seeing him at her school, and had realized he didn’t fit in.”

As early as the spring of 1915, King was starting to show annoyance at having to fend off Fitzgerald’s insinuations about her thoughts and love life. “Never say again that I’m going to marry Deering!” she scolded in November of 1915. She responded to Fitzgerald’s complaint that she permitted him to idealize her by saying, quite sensibly, whose fault is that? “She got the feeling that Fitzgerald was more interested in her as a character than as a human being.” Says West.

On July 15, 1918, she writes to tell him that on the following day she will announce her engagement to William Mitchell, in what her granddaughter believes was something of an arranged marriage between two prominent Chicago families. “She was a willing participant, I’m sure,” says Chandler. “My grandfather was drop-dead handsome and a real charmer. What I don’t think they ever figured out was what it was going to be like to live in the same house together.” In a sense she made the same choice Daisy Buchanan did, accepting the safe haven of money rather than waiting for a truer love to come along. Sports would remain a passion. She rode, shot, and spent hours working on her golf game with Edith Cummings, another of the Big Four, who won the 1923 U.S. Women’s Amateur and appeared on the cover of Time magazine as The Fairway Flapper. Cummings, whom Fitzgerald probably knew through King, seems to have been the inspiration for Jordan Baker, Daisy Buchanan’s more likable, down-to-earth friend.

King and Mitchell had three children in a marriage that lasted 19 years. She then went off with John T. Pirie, a married Lake Forest businessman, leaving broken hearts on both sides. Pirie, an outdoorsy type who raised springer spaniels, was a much better match for King. She later founded that Ladies Guild of the American Cancer Society and was active in local arts.

She saw Fitzgerald for the last time in 1937 in Hollywood. He was writing for the movies and trying to stay on the wagon. “She was the first girl I ever lover and I have faithfully avoided seeing her up to this moment to keep the illusion perfect,” he wrote his daughter, Scottie, shortly before the planned meeting. “I don’t know whether I should go or not.”

He was right to worry. He drank and, according to the account King gave her granddaughter, looked a sad sight. King asked Fitzgerald if she was one of the characters in The Beautiful and the Damned.

“Which bitch do you think you are?” he replied.

Chandler points out that it is impossible to know how he said this. West, too, thinks it sounds too harsh for Fitzgerald: “He might have said it playfully rather than savagely. That sounds more in character for him. He was not a cruel man.”

It was a sad final memory for King, who never made a big deal of their relationship. “She was very nonchalant about it,” says Chandler. “She knew he was a great writer, but I don’t think she ever considered herself a big part of the story.”

This was originally published in the November 5, 2003 issue of PAW.

No responses yet