System Failure: Economists Who Uncovered American ‘Deaths of Despair’ Explain the Causes

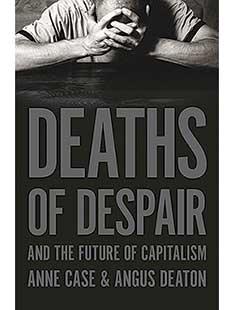

Faculty Book: Anne Case *88 and Angus Deaton

“Many lower-wage jobs do not bring the pride that can come with being part of a successful enterprise.” — Professor emerita Anne Case *88

Both Case and Deaton are professors emeriti jointly appointed in the economics department and the Woodrow Wilson School. Deaton received the 2015 Nobel Prize in economics. The two, who are married, spoke with PAW about fraying social connections, the effects of unaffordable health care, and the solutions they propose.

What you call “deaths of despair” were deaths that occurred mainly among those without a bachelor’s degree.

Deaton: There is a dramatic divide between those who have a B.A. and those who don’t. Our current economy benefits those with a B.A., and hurts those without it.

What other factors hurt working-class Americans?

Case: There’s been a deterioration in the quality of jobs and stagnant wages. And there’s much less attachment today between employer and employee. Work brings one status and a sense of self — feeling part of a bigger whole — and many lower-wage jobs do not bring the pride that can come with being part of a successful enterprise.

How does our healthcare system add to the difficulties?

Deaton: What is profoundly different about the U.S. economy is the cost of our healthcare system and the way we fund it. It costs a lot more than anywhere else, and we fund a lot of it through employers, which puts a huge burden on people’s wages. A family policy on average costs $20,000, which is paid by the employee and the person’s employer. For people with low wages, that’s sort of a catastrophe. It’s holding down their wages and destroying jobs.

What is the societal fallout compounding these issues?

Case: Without a good job, it’s hard to get married. If you can’t get married, you cohabit, and cohabitations are very fragile. You may not have family that supports you; if you are a man, you may not see your children much. Other structures have frayed — attachments to organized religion and to unions. This is a [sociologist Émile] Durkheimian recipe for suicide, and that is what we’re seeing happen. Suicides continue to rise, along with alcoholic liver disease.

“What is profoundly different about the U.S. economy is the cost of our health-care system and the way we fund it.” — Professor emeritus Angus Deaton

What solutions do you propose?

Case: I don’t see us getting back on track until we are able to rein in health-care costs. The health-care industry is taking 18 percent of our gross domestic product. That’s a cancer eating the economy from the inside out. Reining in costs will call for a concerted effort that, currently, there does not appear to be the political will to do.

Deaton: Two things are needed to make the health-care system work: a system that makes sure, one way or another, that everyone is insured, for example by enrolling people at birth, and some form of cost control.

More generally, it would be good to try to redress the growing power of corporations relative to workers and consumers. And workers need more of a say in what corporations do. We are in favor of a higher federal minimum wage.

What’s next for you?

Case: I’m continuing this work on deaths of despair. I am extraordinarily worried about the children in these families. They are at risk for much worse outcomes because of the atmosphere in which they have been raised.

Deaton: I think I might retire and write my memoir.

Interview conducted and condensed by Jennifer Altmann

No responses yet