Faculty Book: James Alexander Dun *04: Another Revolution

A young America looked toward the possibilities of upheaval in Haiti

At the end of the 18th century, three revolutions upended the status quo in countries across the Western Hemisphere. Two of them — the American Revolution and the French Revolution — are staples of high school history, seen as touchstones that challenged political absolutism and feudalism and laid claim to an ideology of natural rights.

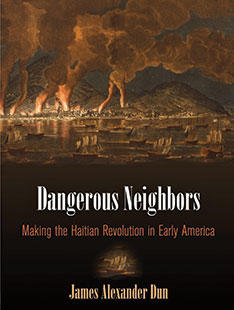

But the third revolution, which culminated in political independence and the abolition of slavery for the French Caribbean island colony of St. Domingue (now Haiti), is less well-known. In his new book, Dangerous Neighbors: Making the Haitian Revolution in Early America, assistant professor of history James Alexander Dun *04 explores the shifting meanings that early Americans gave to the events in St. Domingue as they unfolded between 1789 and 1804. The unrest became fuel for debates about slavery and equality in the young United States.

“People today tend to think about Haiti as this tragic place, a failed state,” says Dun. “And until recently, the Haitian Revolution was considered to be primarily violent and anarchic — without the important questions of rights that accompanied the American Revolution. But for people around the Atlantic at the time it was happening, there were moments of great praise, of horror, of excitement. People were seeing it as an important development in their history.”

To trace how American attitudes toward the Haitian Revolution evolved, Dun focused on Philadelphia, the nation’s capital and a hotbed of abolitionist sentiment. Americans who traveled to and from the Caribbean brought reports of the events in St. Domingue: a massive and bloody slave insurrection sparked by the promises of the French Revolution, the abolition of slavery in the colony, and the subsequent struggle by black leaders like Toussaint Louverture to gain political autonomy for Haiti.

For some American radicals, Dun says, the Haitian Revolution was a test of the possibilities of the French and American revolutions. Could the promise of full citizenship mean freedom and political rights for the slave populations in France’s colonies? “It made sense that freed slaves could become French citizens and fight for French armies,” Dun says. “But there was also a trickier question: Might they come to the United States and be citizens here, too?”

Slaveholders saw the rebellion on St. Domingue differently. “The planters knew about slave insurrections, and this was a particularly big and scary one,” Dun says. Some Northern abolitionists saw race as fluid and subject to environmental factors, which made the prospect of freed slaves less threatening. But to Southern plantation owners, slavery represented a natural hierarchy fixed by God — one that the Haitian Revolution was threatening to upset. These divisions quickly became political.

In the end, apprehension about the revolution’s ripple effect won out. The United States did not recognize Haiti as an independent nation for more than 50 years. But it’s important, Dun says, to recognize the “flexibility and fluidity and color” of the story as it happened. “This was a moment when some Americans were looking to Haiti and seeing a raceless model of citizenship that seemed to them like an extension of their own revolution.”

No responses yet