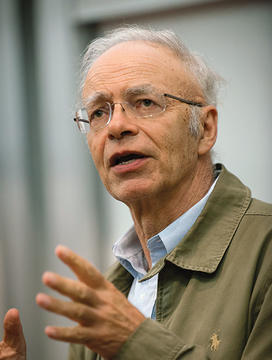

Faculty Book: Peter Singer on Our Moral Obligations to the Impoverished

Peter Singer believes those who live in prosperous nations do too little to help alleviate poverty in low-income countries. “It’s morally indefensible,” says Singer, the Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at Princeton, who has released a new edition of The Life You Can Save: How To Do Your Part To End World Poverty on the book’s 10th anniversary. He spoke with PAW about why we should care about global poverty.

Why release a new edition of the book?

A lot has changed in the past 10 years. When the book first came out, 1.4 billion people were in extreme poverty. Now that number is 736 million. It means that extreme poverty is a problem we are making progress on, and we could see it eliminated. People say, “Poverty is always with us. It’s pouring money down the drain.” There’s good evidence that is not the case.

Why release the book through your nonprofit, also called The Life You Can Save, instead of through a traditional publisher?

This was another reason for bringing out a new edition. I wanted to make the ebook and audiobook versions free. So far, we’ve had close to 14,000 people download them. [Visit www.thelifeyoucansave.org to download.]

You are most concerned with addressing extreme poverty found in low-income countries. What about someone who says, “I prefer to help someone down the street”?

I don’t want people to stop helping the soup kitchen nearby, but I want them to be aware that the money will go a lot further in countries with extreme poverty. If somebody lives on $700 a year and you have $1,000 to contribute, you can make a life-transforming change in that family.

You have said that it is much more important to donate to nonprofits that alleviate suffering than to art museums.

I’m not against art. I think the creative drive of artistic expression is important, but the amounts of money spent on artworks by museums, or on putting on lavish operas, have nothing much to do with encouraging creativity. Given the great amount of need, I don’t think a museum should purchase a $100 million work of art when that money could restore sight to 2 million people by funding their cataract surgery.

What do you personally give?

My wife and I started giving back in the 1970s, when I was a graduate student. We began with 10 percent, and we’ve gradually upped that. For the last 10 to 15 years, we’ve given a third of our income, and we are working to get closer to half.

You say most people don’t give because they think reducing extreme poverty is a hopeless task. Can you explain why it’s not?

As I said, we are making remarkable progress in reducing extreme poverty. But if we ask what difference one individual can make, I would say don’t focus on the whole problem, but on what you can do for individual people. Think about someone you love — imagine that person going blind because they develop cataracts and can’t afford the simple surgery that everybody in America can get under Medicare or Medicaid, even if they don’t have any other health insurance. Think about how much difference it would make to get that operation, and the relatively little difference that $50 makes to you — $50 that can pay to restore someone’s sight.

Studies have shown that if you give very poor people a single cash sum, they are likely to, for example, replace their thatched roof with an iron roof, and in a few years that’s going to save them money because the thatch had to be replaced every year. So people’s lives can become better off through quite small sums of money.

What are a few of the nonprofits that you recommend people donate to?

The Fistula Foundation has funded more than 40,000 obstetric fistula surgeries in 31 countries. The food programs of Project Healthy Children have helped more than 55 million people. GiveDirectly has provided cash transfers to more than 100,000 households and is running a randomized control trial to study the impact of universal basic income. I also recommend giving to The Life You Can Save itself, because that helps to generate more donations to these and other effective charities. For every $1 that The Life You Can Save spent in 2019, we know that those who visited our website went on to donate $13 to the charities we recommend.

What effect has the book had in the last 10 years?

The book has reached many people who have given more, or more effectively, as a result. Some of these readers are very wealthy. Cari Tuna, the wife of Dustin Moskovitz, the co-founder of Facebook, read it and, as a result, she and her husband set up a foundation called Good Ventures that supports a lot of organizations in the effective altruism movement [which uses an evidence-based approach to evaluate which nonprofits are the most effective]. So it’s definitely caused very significant sums to flow in positive directions.

What reactions do you get from your students?

I’ve had students who changed their life choices. One student who took my course a few years ago is helping The Life You Can Save get set up in India. Another student had an offer to work on Wall Street, and he decided he would do the most good by accepting that offer. So he is earning very well — and giving away half his income.

This is an expanded version of an interview published in the March 4, 2020, issue of PAW.

Interview conducted and condensed by Jennifer Altmann

3 Responses

Rocky Semmes ’79

5 Years AgoEndorsing Beauty

It is a puzzling but pleasing paradox that Don Michael Randel ’62 *67’s criticism of Professor Peter Singer (Inbox, April 8) is clearly but the same song sung by Professor Singer but in a different key — they each represent the same school, figuratively and literally.

Singer posits that no “museum should purchase a $100 million work of art when that money could restore sight to 2 million people by funding their cataract surgery” (Life of the Mind, March 4). In turn, Randel supports museum spending in appreciation of “the beauty in art and nature” and the creation of “beautiful things.” Each, respectively, is supporting beauty and what is beautiful. Singer endorses the beauty of charity. Randel endorses the beauty of fine art.

These two good people are endorsing the same theme, but from varied points of view. The theme is beauty. Each echoes the wisdom of the English Romantic poet John Keats, who blessed us all with the recognition that “beauty is truth, truth beauty — that is all/ Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” Amen.

Norman Ravitch *62

6 Years AgoHelping the Impoverished

What is impoverishment? In America if you cannot buy every electronic device, subscribe to every sports program, and have two or three SUV vehicles in the driveway you are impoverished. And it makes you vote for Trump out of anger. In other places not having enough good food to eat is the definition. In some parts of Europe, not having the latest shoes or purses is impoverishment. We need some definitions. It looks like some people even with trust funds are impoverished, according to one of your articles.

Don Michael Randel ’62 *67

6 Years AgoOn Charitable Giving

Professor Peter Singer doesn’t “think a museum should purchase a $100 million work of art when that money could restore sight to 2 million people by funding their cataract surgery” (Life of the Mind, March 4).

This facile comparison obscures many things that charitable dollars can and should do even just in the domain of sight. Shouldn’t we want to develop the capabilities in people that sight confers? Given sight (whether or not enabled by medical interventions), should we not want to spend money to teach people to read, to enable them to appreciate the beauty in art and nature, and perhaps even to create beautiful things? One might even want to spend money on museums. These might well be moral obligations.

Editor’s note: The author is a former president of the University of Chicago and the Mellon Foundation.