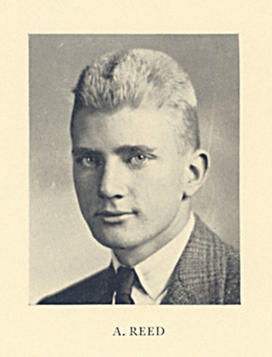

Not everyone thrives at Princeton. In the spring of his senior year, Alan Reed ’40 felt a “loss of interest in his work,” he complained to a doctor in McCosh Infirmary, and “a sense of futility about my whole university experience.” He had decided to quit college, although “the consensus of opinion is that I am making a mistake.”

Dean Christian Gauss was sorry to hear it, for he had befriended the unhappy student from Philadelphia. He considered himself an expert on this Princeton type, the sons of plutocrats: “the spoiled-child pattern,” he called it. Reed’s father died when the boy was young; Reed’s mother doted on him and, after high school, sent him around the world on a vacation that included a tiger shoot in Indochina.

The charming Reed enjoyed Princeton until bicker somehow went wrong. Then he began to display, the administration noted, “a lack of ordinary discipline and over-indulgence.” One night he got into a fight with a fellow student in front of the Nassau Inn. Reed drunkenly waved a Colt automatic, then stumbled back to his room for a bayonet before proctors seized him.

Though remorseful, Reed was expelled in 1938 and enrolled at Penn. Gauss blamed Reed’s mother, who admitted “his discipline has been lax and light,” since she adored him so.

Reed returned to Old Nassau with encouragement from Gauss, but left for good in March 1940. He joined the Navy, thinking he had heard the last of Princeton.

Not so. In wartime four years later, Lt. Reed volunteered to lead a detachment from the USS Birmingham to fight fires on a stricken aircraft carrier at Leyte Gulf. Then the carrier exploded, and hundreds died.

“Alan is dead — killed in the Pacific — his Mother,” says the trembling scrawl on the fundraising letter she returned to the University weeks later. “Despite the constant danger,” Reed’s posthumous Navy Cross award reads, “he fearlessly boarded the Princeton in the face of raging flames.”

No responses yet