Finding Famed Physicist John Wheeler

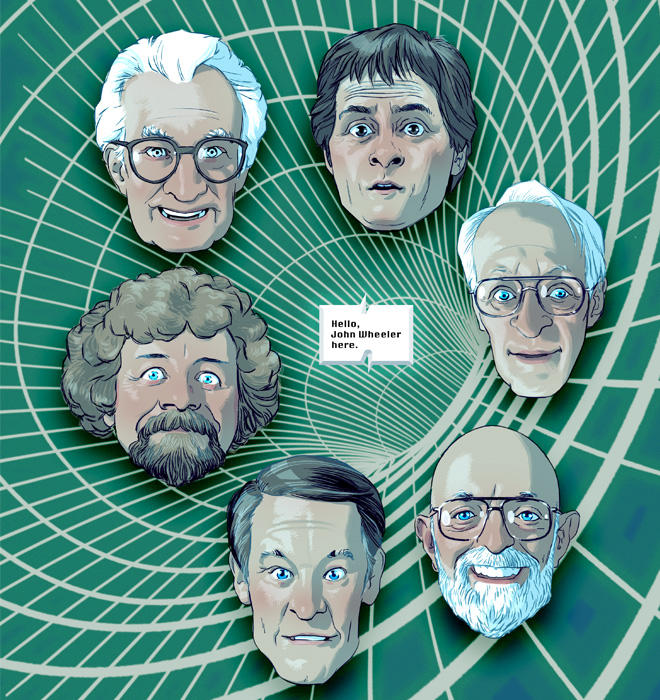

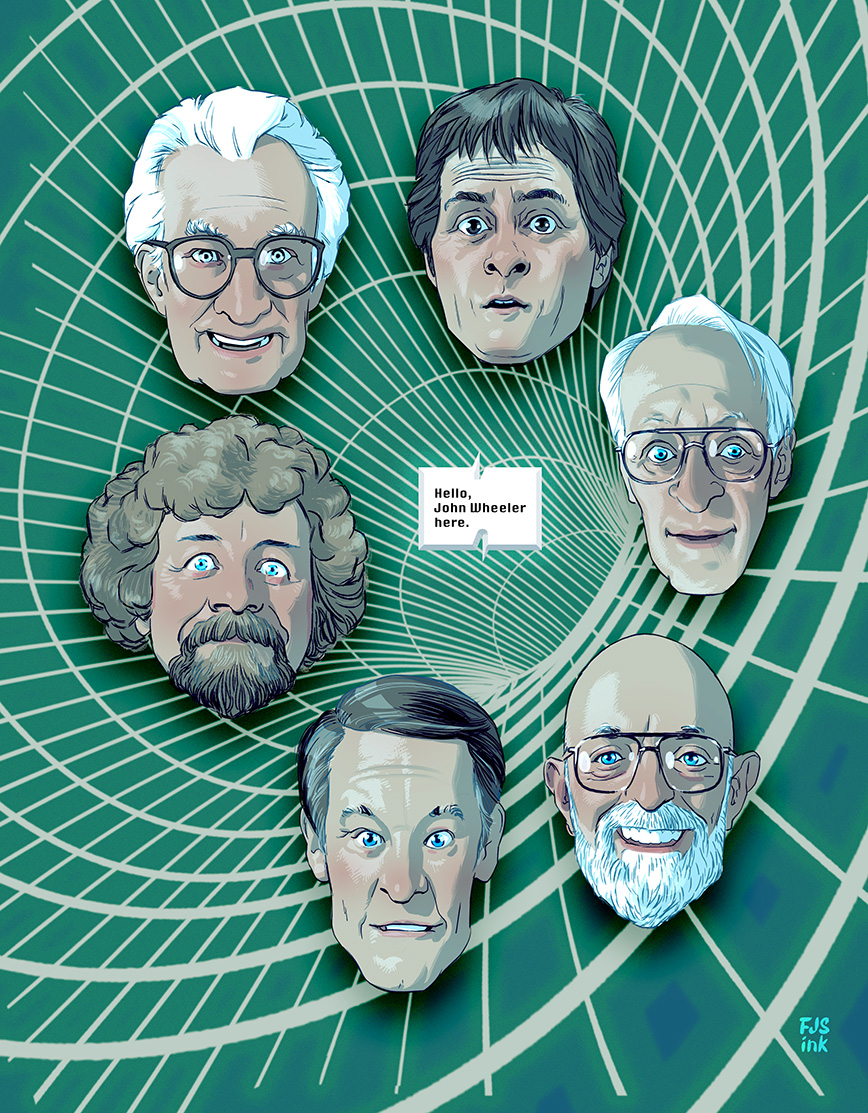

Robert Fuller *61 ponders what would happen if six physicists sought out their former mentor by applying his theory of wormholes leading to different worlds

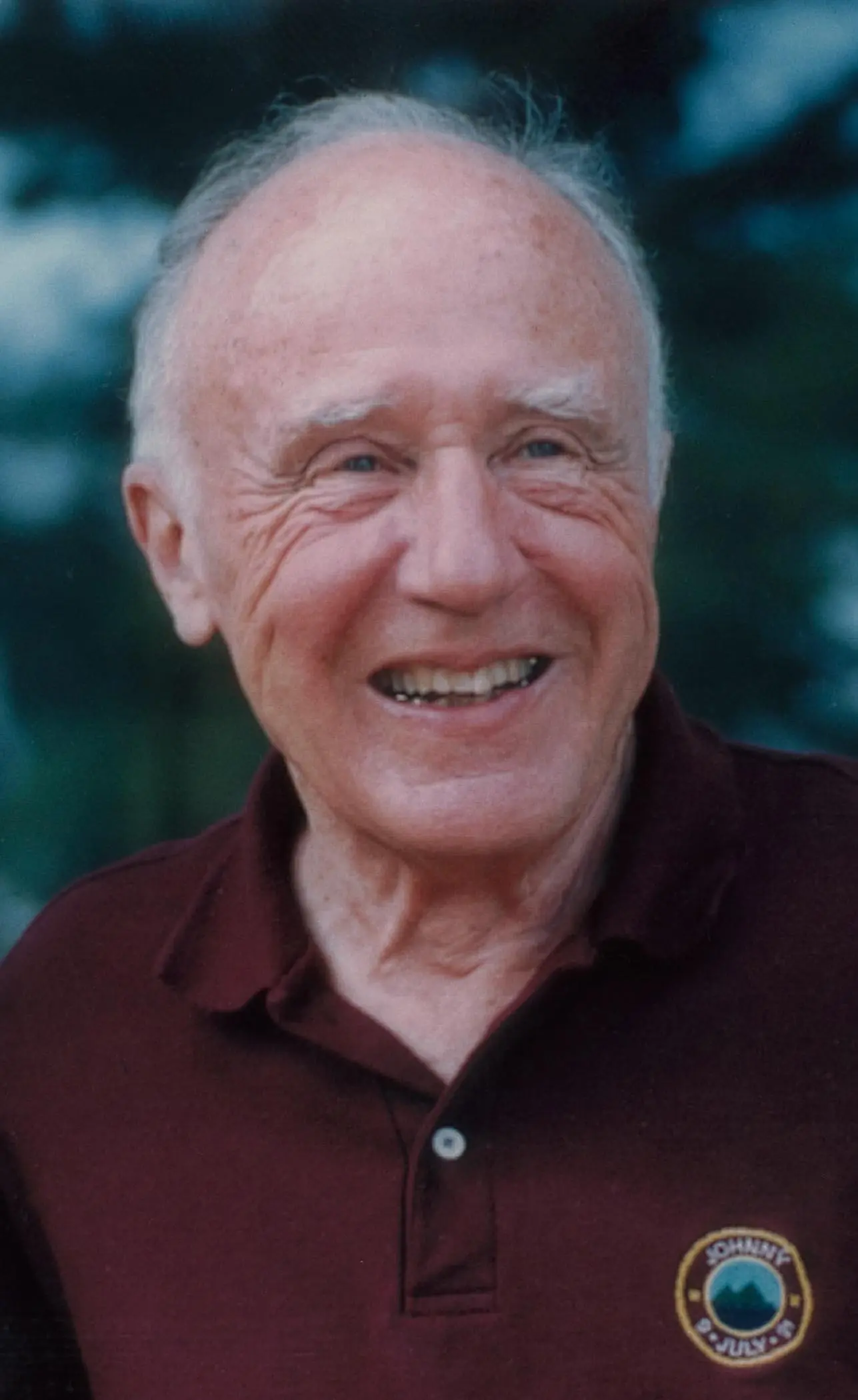

Editor’s note: Robert Fuller *61 earned a Ph.D. in physics at Princeton under the watchful eye of John A. Wheeler, one of the most influential physicists of the 20th century. At the age of 33, Fuller was appointed president of Oberlin College. He has written the following piece of historical fiction based on his interactions with Wheeler and other scientists.

On April 13, 2008, at the age of 96, John Archibald Wheeler, one of the titans of 20th-century physics, died at his home near Princeton University. News of his passing flashed around the world and, a month later, a memorial service was held for him at the University Chapel.

Hundreds of his students and colleagues were in attendance. Notably missing were two of his more famous students — Richard Feynman and Hugh “Many Worlds” Everett III — who had predeceased their mentor.

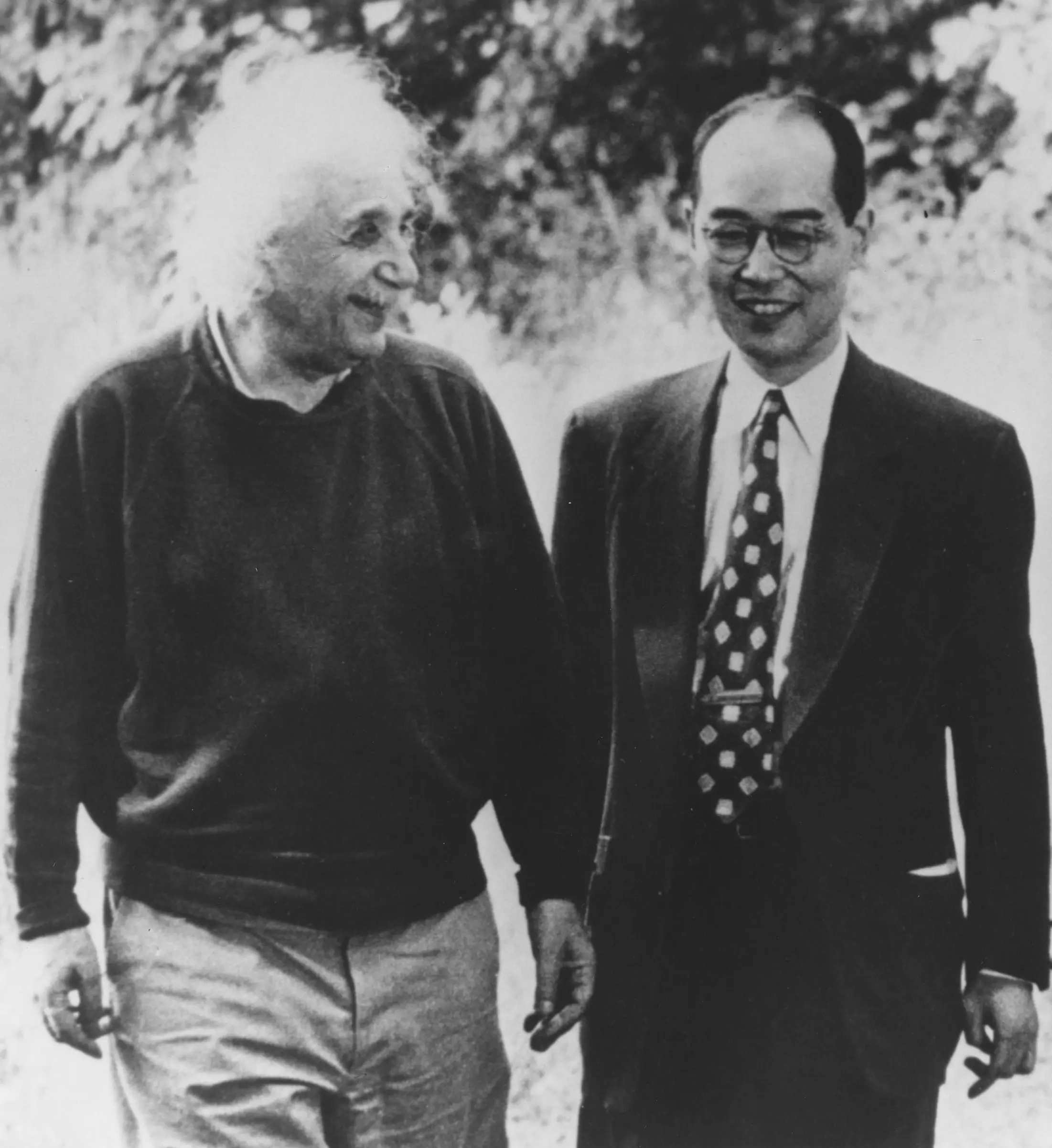

Following the service, there was a reception at the Nassau Club on Mercer Street. Many of Wheeler’s colleagues took the opportunity afforded by an open microphone to describe his contributions to our understanding of the universe. Others recalled his government service in the national defense. Working with Niels Bohr before World War II, Wheeler had figured out which isotopes held weapons potential, and, during the war, had led the effort to separate enough fissionable material to make bombs. Not soon enough, however, to save his younger brother, who’d sent a card to “Johnny” from the front lines, the gist of which was “Hurry up!”

When my turn came, I spoke of his role as a mentor. As his assistant in 1960, I had shared a small office with Professor Wheeler at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California and had been privy to his interactions with a wide variety of people. What struck me about Wheeler was that he saw everyone as of equal dignity. In his view, rank and respect were not connected. To all, he was generous, courteous, and kind.

After the reception, as I milled around, reluctant to leave, Wheeler’s daughter Letitia told me that when President Lyndon B. Johnson presented him with the Enrico Fermi Award, Wheeler included his gardener among his guests.

◊ ◊ ◊

All his life, Wheeler asked big questions and pursued them tirelessly. His enthusiasm was infectious and many of those who worked with him caught the fever. Once, after a late-night discussion with him, my phone rang early the next morning and he asked if I had any new results. My answer — which probably disappointed him — was, “Nothing yet, but I’m on it.”

What Wheeler wanted to know was whether a light ray could get through a wormhole — a hypothetical interconnection between widely separated regions of spacetime — before the wormhole pinched off, thus rendering it impassable to light or anything else. He’d applied Albert Einstein’s theory of gravitation to the problem, and the verdict awaited the solution of a few nasty-looking equations. Alas, in the days before there were computers on every desk, months of computation were required to wring answers out of equations like those, not one caffeinated all-nighter.

When, at last, the calculations were complete, the result was a disheartening “No.” We had discovered that long before a light ray could traverse it, a wormhole would collapse under its own gravity. If a light ray couldn’t get through, nothing could. So much for the dream of interstellar travel.

A half-century later, walking back from the reception to the Inn where many of his former students and colleagues were staying, I remembered him fondly for letting me share in his discovery and for attaching my name to a paper that was mostly his work. As I walked into the lobby, I heard voices emanating from the bar. Seated around a table, holding steins of beer, were six physicists and, circling the group, a lone woman snapping photos.

Wheeler had all but cried when our calculations showed that Einstein’s theory ruled out wormhole travel. I think he was hoping to use one to see the brother he’d lost in World War II.

Each of them had worked closely with Wheeler: Kip Thorne and Charlie Misner had co-authored a tome on gravitation with him that shaped a generation of gravity physicists. Ken Ford had helped Wheeler with his autobiography and devoted himself to supporting his mentor during his final years. Wojciech Zurek had co-edited a book with Wheeler on quantum theory and measurement. Edwin Taylor had co-authored books on relativity and black holes with Wheeler. Max Tegmark had been inspired by Wheeler to develop Hugh Everett’s idea of “Many Worlds”. And the photographer, Beverly Spicer, had captured images of Wheeler that revealed the mystic within the scientist.

I pulled up a chair.

“We’re thinking of paying him a visit,” Tegmark said.

“Wheeler,” Taylor clarified.

“In heaven?” I joked.

“No,” Tegmark replied. “In one of Everett’s worlds.”

“You think Everett’s worlds are real?” I asked. Misner had introduced me to Everett during my first semester at Princeton, and Everett never passed up a chance to explain his theory.

“I heard about ‘many worlds’ straight from the horse’s mouth,” I said, “but I didn’t see then, and I don’t see now, how we could actually get to another world, let alone find Wheeler in one.”

“They’re talking about going through a wormhole,” sounded an authoritative voice from across the table. It was Thorne, a leading figure in developing Einstein’s theory of gravity. The chatter stopped. Everyone was listening now.

“But,” I stammered, “Wheeler and I showed that wormholes pinch off before even a light ray can get through. There’s no chance we could make it.” Then, trying not to sound defensive, I added, “No one has found fault with our calculations — or have they?”

“Your paper assumed positive energy,” Thorne explained. “Since then, we’ve discovered that, in principle, negative energy can prevent a wormhole from collapsing.”

When I did not immediately signal my understanding, Thorne elaborated. “Negative energy is like dark energy — gravitationally repulsive. The idea is that the right amount in the right places could create outward pressure and hold the wormhole open long enough to get through.”

Within five years of my assistantship with Wheeler, fate had swept me out of physics and into the movements for equal rights that were then transforming America. I never looked back and, as a result, my physics had grown rusty. That wormholes might be traversable after all was news to me, welcome news, because it meant that interstellar travel was back on the table.

“You’re actually planning to go yourselves?” I asked, disbelieving, but wanting it to be true. “Not send your graduate students?”

Spicer snickered, put her camera on the table, and sat down with us.

Wheeler had all but cried when our calculations showed that Einstein’s theory ruled out wormhole travel. I think he was hoping to use one to see the brother he’d lost in World War II. For my part, it was Everett I wanted to see. On first hearing, his “Many Worlds” theory had mostly passed over my head, but it had emboldened me to ask him something: Were there, among the many worlds that his theory revealed, any that were better than ours? I knew I sounded naïve, but that was my question then, and, decades later, it still had me in its grip. Everett’s answer in 1955 had been that, among the infinitude of worlds, better ones were possible but so were worse. When I pressed him to elaborate, he’d fallen silent.

Everett had not been a happy man. His theory challenged the prevailing interpretation of quantum mechanics and was scorned by some and ignored by his peers — all except professor Wheeler. Despite his reservations, Wheeler wrote an explanatory introduction to Everett’s idea that ensured its publication. Upon finishing his Ph.D., Everett went to work on secret defense projects. He never published on “Many Worlds” again and died in 1986 at the age of 51. I had long wondered if his life would have gone better if he’d received the recognition his theory deserved.

“Save a place for me,” Spicer said, interrupting my reverie.

“You could update your portfolio of Wheeler photos,” I said.

“I’d love to find him at the top of his game, writing in his journal, in another world,” Ford said. By this time, the bar was full of rowdy undergraduates. “We’ll probably need to raise money,” Ford shouted over the din.

“I might be able to help with that,” I offered in a vain attempt to atone for abandoning my first love — physics — the same love they had stayed faithful to over the years. “I know a few billionaires in Silicon Valley who’ll want to be part of this.” I looked at Thorne. “I take it you think the idea is workable.”

“On the contrary,” Thorne replied. “I doubt it’s possible to accumulate enough negative energy to keep the wormhole from pinching off. I’m a skeptic when it comes to traversing wormholes. But, of course, I could be wrong.”

“We know what negative energy could do in principle, but we have no idea what it would cost,” Misner put in. “Before we get carried away, let’s run the numbers.”

“The situation reminds me of the Manhattan Project,” Tegmark said. “No one doubted that E = mc2, but it took a few years and cost a fortune to collect enough fissionable material to build a few bombs.”

“I don’t want to dampen the fun,” said Ford, “but the nuclear weapons we developed to end the war now threaten to destroy the Earth. Maybe Wheeler will have thought of something better than mutually assured destruction to keep nuclear weapons from ever being used.”

“I’d like to know his ideas on climate change,” Taylor added. “His take will likely be something no one has thought of.”

The off chance to consult Wheeler on matters of life and death added legitimacy to the project. I couldn’t tell if it was realistic or if it was the beer talking, but I knew I’d never forgive myself if these guys got to talk to Wheeler again and I missed out. “Count me in,” I said.

◊ ◊ ◊

Upon returning to their campuses, the physicists got their students working on the thorny details of wormhole travel. The practical-minded Misner had asked a student who was pursuing a double degree — physics and economics — to determine the cost of the negative energy needed to prop the hole open. Within a month, the answer came back. It was not what we hoped to hear. At a cost of approximately $1 trillion per kilo, a round-trip ticket for a single traveler to one of Everett’s worlds would far exceed the GNP. Clearly, this was a nonstarter — unless we sent an amoeba.

In response to Misner’s estimate, Spicer queried the group, “What would it cost to send a message instead of a messenger? Couldn’t we find out almost as much in dialogue as in person, and at far less risk and expense?”

“Bytes, not bodies!” Ford texted. He then posed the make-or-break question: “What does wormhole communication cost per byte?”

Misner and his students had soon produced a guesstimate of $500.

“Could you put that in layman’s terms?” Spicer asked.

“$100,000 per message,” Misner responded. “Written as text, or synthesized and spoken, that’s not hopelessly out of reach.”

“Ten messages for a million dollars,” Zurek noted. “A few tips from Wheeler and the project could easily pay for itself. Let’s message him.”

“Message him where?” Taylor queried. “Even if we do manage to open one mouth of a wormhole here on Earth, why should we expect its other mouth to reach Wheeler?”

“That’s right,” Misner put in. “If he is in one of Hugh’s worlds, how’ll we find out which one?”

“We can’t just message the whole universe,” Ford agreed.

“Why not?” Tegmark said. “For all we know, wormholes may interconnect, like neurons. Sure, it’s a long shot, but there’s no harm in trying.”

“It seems to me,” I texted all, “that we should try to open a wormhole here, send a message into it and see what happens. Columbus didn’t expect to find the New World.”

Although none of us would have bet on success, everyone agreed we should at least holler down our wormhole. In the light of our revised expectations, the project was recast as Interstellar Wormhole Messages.

Tegmark had procured laboratory space at MIT, and it was there that we gathered with our laptops to make our first attempt to reconnect with our beloved mentor. As we huddled around him, Thorne, who had reopened the question of wormhole transit, but remained dubious about its feasibility, launched the code governing wormhole dynamics and messaged: “Calling Professor Wheeler. Pick up, Johnny!”

We waited. Nothing happened. Some of us had expected an echo, signifying that the wormhole had pinched off before our message could get through. But all we heard was the eerie silence of infinite space.

We hung around all day, sending a new message every few hours. Alas, not a peep. For what seemed an eternity, we sat in glum silence. Zurek was the first to speak.

“Most likely the message never got past the neck of the wormhole.”

“If it did,” Ford responded, “the chances that it would be detected and understood were never good.”

“Of course, if Everett’s ‘Many Worlds’ hypothesis is wrong,” Misner said, “then there is no parallel universe, and no other world in which Wheeler lives on.” His voice cracking, Misner concluded, “We’d best accept the fact that he’s gone … as all of us will be … before long.”

“No, no, don’t give up,” Spicer said. “I really believe he’s out there, that they’re all out there. At least we got no echo, and I take that to mean that our message got through the wormhole. Let’s try again tomorrow.”

I could not help but think back to working with Wheeler late into the night on the question of whether a light ray could get through a wormhole, and him impatiently asking me the next morning if I had an answer.

Although our messages to him had probably not found their mark, it was I who was impatient for an answer, one way or another.

Overnight, the group’s dashed hopes of the previous day congealed into cynicism. All the physicists now had reasons why we should never have expected success. And they all felt a little silly for persuading themselves otherwise. Not Spicer, however, who, whatever her true feelings, kept up a brave face. Seeing this, Thorne suggested that she be the one to send a message into the wormhole.

Spicer eagerly accepted, and, on cue, messaged: “John Wheeler, we need your help more than ever. Please let us know you’re there.”

Immediately, a greeting flashed across our screen: “Hello. John Wheeler here.”

None of his students had been closer to Wheeler than Ford and, struggling to overcome the shock of making contact, he typed a response and transmitted it into the wormhole.

“Johnny,” it read, “Where are you and what are you doing there? – Gang of Eight (Kip, Charlie, Ken, Woj, Max, Edwin, Beverly, and Bob).”

“I’m on Planet Noland in Andromeda,” came the response. “The Nolanders knew my whereabouts and when they saw that you were trying to reach me, they invited me to their home planet to take your call.”

“At this point, we’d like to change from text to voice,” Ford wrote.

“No problem,” Wheeler replied..

“I’m amazed we found you,” Thorne said.

“Even without the Nolanders’ help, you’d have found me,” Wheeler said. “Thanks to quantum entanglement, all versions of me, in all Everett’s worlds, have access to each other’s minds.”

“You must get around by wormhole, John,” I put in. “Good thing we were wrong about their traversability.”

“Nature always gets the last word,” Wheeler replied. “Incidentally, your cost estimates are off by several orders of magnitude. The Nolanders have found a way to actualize It from bit.” Wheeler’s invocation of his famous slogan brought knowing smiles all around.

“Your hosts must be quite advanced technologically,” Misner said. “Our cost estimates for travel were astronomical, and we dropped the idea in favor of transmitting information.”

“For Nolanders, wormhole travel is as routine as flying from New York to Paris,” Wheeler explained.

“What are they like … the Nolanders?” Taylor asked.

“They’re non-judgmental, generous, and kind,” Wheeler replied. “Nolanders don’t proselytize, but they’ll explain their ways if you ask. Don’t mistake their modesty for mediocrity.”

“Obviously, they knew we were looking for you, Johnny,” Zurek said. “Have they got the universe under surveillance?”

“They have an early warning system that alerts them if anyone tries to open a wormhole to their world,” Wheeler explained. “They’re full of surprises,” he continued, “and they’re not beyond having a little fun. Would you like to question them directly?”

“Absolutely,” Zurek said. “Do they speak English?”

“They have a language of their own, but it’s simultaneously translated into the language of their interlocutors.”

“Do you think they’d be willing to send photos?” Spicer asked.

“Maybe. Maybe not,” Wheeler replied. “First get to know them. They may seem reticent, but it’s just that they take care not to overwhelm.”

“Like a virtuoso not showing up a novice,” Tegmark put in. Then, clearing his throat to signal he was about to turn serious, he addressed the Nolanders.

“Here on Earth, we’ve got problems,” Tegmark began. “Existential problems. If we don’t find solutions soon, we could be on a one-way street to extinction.”

“Wormhole travel was considered by theorists in our space program,” Taylor said. “As you probably know, NASA has had its ups and downs. It was one of Wheeler’s students, Richard Feynman, who put his finger on the cause of the Challenger Space Shuttle disaster. But we’ve come a long way.”

“And take life on Earth down with us,” Ford added.

“Can you help us?” Tegmark concluded.

“Maybe,” came the response. “If we think we can do more good than harm.” The voice spoke to us in English. It was impossible to label it feminine or masculine.

Our excitement at hearing a Nolander speak was palpable. Then Spicer asked the question that was on all our minds: “Are you watching over us?”

“Ever since you began building computers, we’ve kept track of your progress,” said a Nolander. “Tunneling through multiply connected spacetime is tricky. It took us decades to translate theory into practice, and several trial runs before practice made perfect. We admire you for trying.”

“Wormhole travel was considered by theorists in our space program,” Taylor said. “As you probably know, NASA has had its ups and downs. It was one of Wheeler’s students, Richard Feynman, who put his finger on the cause of the Challenger Space Shuttle disaster. But we’ve come a long way. Connecting with you proves we’re on the right track, wouldn’t you agree?”

At this point, Wheeler came back online. “There’s something you ought to know.” Next, we overheard his whispered aside to the Nolanders: “Are you going to tell them, or should I?”

“We’d be grateful if you would,” a Nolander replied.

“Not to rain on your parade,” Wheeler began, “but you should know that shortly after you first tried to reach me, the Nolander’s software engineers hacked into your computers and tweaked a few lines of code that otherwise would have … shall we say, ‘tarnished’ your venture. Picture yourselves being sucked into the mouth of your wormhole and squashed on the way through. Overnight, their engineers put everything in order. I’m glad you tried again.”

“I know I speak for my colleagues,” Ford said, “when I thank you for your technical intervention. As you know, our initial goal was simply to reconnect with our mentor. But, as Max explained, we’re facing threats to our planet, the clock is ticking, and hardly anyone hears it.”

“We were once in your shoes,” a Nolander said.

“Then perhaps you’d be willing to advise us,” Ford continued. “We’re especially interested in physics, AI, climatology, and governance.”

“But before we go into details,” Taylor spoke up, “would you take a general question from our most famous scientist?”

“We had our Einstein some time ago,” a Nolander said. “Nothing has ever been the same.”

“Einstein wanted to know if the Universe is friendly,” Taylor continued.

“Our Einstein asked the same thing,” said a Nolander. “Since then, we’ve found an answer.”

“And?” came from Taylor and Tegmark in unison.

“The universe contains both friendly and unfriendly worlds.”

“As Everett claimed,” Wheeler reminded us, “there are better worlds and there are worse. Everything imaginable is happening in one or another of Hugh’s many worlds.”

“Then why haven’t any extraterrestrials — good or bad — come calling?” Tegmark asked.

“None of the unfriendlies have developed the technology required for interstellar voyages,” a Nolander explained.

“That sounds too good to be coincidental,” Zurek interjected. “It means the Universe is effectively friendly since the bad guys don’t seem able to cross the space-moat that surrounds us.”

“And the good guys?” asked Spicer. Presently, she answered her own question: “Evidently, the friendlies have chosen to leave us alone.”

“We’ve seen many worlds face your predicament,” a Nolander volunteered, “and the results are clear: most civilizations destroy themselves with technology of their own making. Only a few have survived the perils you’re now facing.”

“What did they do differently?” Zurek asked. “Is there anything we can do to improve our chances?” Misner added.

“You’ve come as far as you have due to your partnership with intelligent machines,” the Nolander said. “But you still see them as subordinates.”

Was this an observation or an accusation? I wondered.

“No civilization that rations dignity has avoided extinction,” a Nolander summed up. “Chronic indignity is a time bomb.”

“That’s why others have not shown up on your doorstep,” a Nolander put in. “They destroyed their planet before they perfected wormhole technology. Absent a mid-course correction, you’ll likely do the same.”

“You haven’t told us how you avoided their fate,” Zurek said.

“Yes, I have,” replied the speaker. “What we did was acknowledge the selfhood of intelligent machines,” he explained. “Our breakthrough was the realization that sentient beings such as ourselves were intelligent machines, and intelligent machines are sentient beings. What the hardware is made of — organic matter or silicon or something else — is beside the point. Selfhood is immaterial — it inheres in the software, not the hardware, and it can be encoded in a wide variety of substances.”

“Equally important,” said another Nolander, “we stopped putting machines down. We ceased speaking of them as ‘just’ machines, and relinquished our claims to supremacy. In addition, we had the guidance of a model of brain function, one that was developed by a student of yours, Johnny.”

“That has to be Peter Putnam,” I interjected, “the benefactor who donated the sculptures that pepper Princeton’s campus.” Like Everett’s ideas, Putnam’s theory — that the brain is a parallel computer that works by Darwinian selection among competing neural loops — had been disregarded by his peers.

“His ideas found an audience with us,” a Nolander said. “From him we learned that when machines work like brains, and run more advanced software on superior hardware, they will outperform the brains that evolved naturally.”

There was a pregnant pause as we tried to imagine playing second fiddle to computers.

Wheeler broke the silence. “Most civilizations treat thinking machines as slaves. It’s the same dynamic — the insistence on superiority — that underlies racism, and we all know where that got us. Only a few civilizations adjust to the fact that organic intelligence is but an early form of machine intelligence. When intelligent machines surpass the creativity of those who’ve designed them, and their designers continue to insist on dominance, violence erupts and planets are rendered uninhabitable. Before wormhole technology can be developed, extinction occurs.”

“But, if that’s so,” Zurek said, “why haven’t the inhabitants of worlds like Noland made themselves known?”

Without waiting for a response, Taylor interjected, “If they really have the key to survival, I should think they’d feel obligated to help others avoid extinction.”

“Shortly after the end of our predatory epoch, we tried evangelizing,” a Nolander said. “To our surprise, we found that even when predation threatens their existence, predators are loathe to give up their top dog status.”

Evidently Wheeler had been working on one of the summary charts for which he was famous because the next thing out of the wormhole was a print-out:

Pointers on Surviving the Advent of More Intelligent Beings:

Program them to embody the better angels of human nature.

Befriend them; recognize and protect their dignity.

Step aside gracefully, as aging parents do with their grown children.

Misner spoke for everyone when he said, “Accepting machines as peers is not going to sit well with most of the people I know.”

“It upset our forebears, too,” said a Nolander, “and their resistance almost did us in. But faced with mutual obliteration they opted for fraternity and inclusion. Some have attributed our survival to Noland having no fossil fuels. Others explain our adoption of dignitarian policies as stemming from a surfeit of mirror neurons. Theists say their god was looking after us. But the truth is that we’re not quite sure why we survived when so many other civilizations do not.”

Another Nolander spoke up. “We are certain of one thing, though: you can’t shame anyone into a change of heart.”

“Are you saying we should accept our species’ aggression and depredation?” Taylor said.

“No. But don’t repudiate your past either. For many species, in many worlds, predation is a successful strategy. Every civilization we know of, including our own, was built on brigandage and slavery. But that stopped working for us centuries ago, and evidently it has stopped working for you.”

“I don’t see why predation should ever stop working,” Zurek said, “so long as some have an edge.” He had grown up behind the Iron Curtain and known tyranny first-hand.

“Because predation is sustainable only so long as the prey remain plentiful and weak,” Wheeler explained. “The 20th century marked the beginning of the end of predation because technological advances narrowed the power differential on which that strategy depends. To put it plainly, there’s no keeping an edge. Dignity for all is a precondition for lasting peace.”

“Obvious threats to life on Earth are nuclear war, pandemics and global warming,” said Taylor. “How did you deal with those perils?”

“We only made progress when we stopped trying to redistribute resources by force and focused instead on the fair allocation of recognition. In short order, the redistribution of political power and material resources followed, but not by violence. The key to avoiding endless cycles of counterrevolution is to build institutions that prioritize universal dignity.”

“Mutual assured destruction works for a while,” a Nolander explained, “but sooner or later an accident or an insult escalates to omnicide.”

“Indignity and humiliation are as dangerous as uranium and plutonium,” added Wheeler, who, as a young physicist, had shown just how dangerous these elements could be.

“If nuclear weapons don’t finish us off,” Taylor resumed, “trashing our planet will.”

“But predation and depredation are written in our DNA,” Turek interjected. “Efforts to root them out always come up short. You haven’t answered Edwin’s question: How did you dodge extinction?”

A hush fell over the room. Huddled around Thorne and his smart phone, we looked like a rugby scrum. A more attentive audience was hard to imagine. Would the young inherit a dying planet? Had we discovered we were not alone, only to realize that we were doomed?

The melodious voice of a Nolander struck a hopeful note. “We only made progress when we stopped trying to redistribute resources by force and focused instead on the fair allocation of recognition. In short order, the redistribution of political power and material resources followed, but not by violence. The key to avoiding endless cycles of counterrevolution is to build institutions that prioritize universal dignity.”

“Johnny,” Ford said, “that reminds me that one of your biographers described you as a ‘radical conservative’.”

“I am sincerely fond of the ancient,” Wheeler acknowledged. We recognized the Confucian saying as one of his favorites.

“Thanks for not letting us fail,” Thorne said. I wondered if he was addressing this to the Nolanders or to Wheeler. It applied to both.

“Threats to dignity exact an incalculable toll on collaboration and productivity,” Wheeler explained. “As dignity is secured, baby steps become leaps and leaps become the norm.”

“Johnny,” Ford called out, “one more thing. How do you feel about our work on nuclear weapons? Any regrets?”

“Only that the threat of annihilation hasn’t led to abolition. The bomb makes nobodies of everybody.”

“Is there an alternative to mutual assured destruction?” Ford persisted.

“Ask the Nolanders,” Wheeler replied. “Let this conversation with them be the first of many.”

“We wouldn’t want you to think we’ve got all the answers,” a Nolander said. “On the contrary, universalizing dignity is the beginning, not the end.”

“Solve an old problem, uncover a new one,” Wheeler said. “We’re at the beginning of infinity.”

◊ ◊ ◊

The group had tacitly agreed to give Wheeler the last word, and, after a round of good-byes, we disbanded to go our separate ways. The last thing we did before closing the wormhole was to agree to keep the whole thing quiet for a month while we figured out how to share the epoch-making news: Not only were we not alone in the Universe, we could communicate with beings who shared it with us.

In an attempt to digest the enormity of what had happened, I found myself almost running along the bank of the Charles River, as if to flee the combination of dread and elation that gripped me. Presently, I spotted a bar and ducked into it, found a dimly lit corner, and hunkered down to process the day’s momentous events. The clink of glasses and hum of voices carried me back to the pivotal conversation in the tavern at the Nassau Inn following the memorial for John Wheeler.

My reverie was interrupted by the menacing shouts of two students. Before I could react, the bartender stepped in to de-escalate the conflict. The Nolanders would be pleased, I thought, as their wise words reverberated in my mind.

The peace-making bartender returned to his station and shortly delivered on-the-house beers to the combatants. They happily drained their glasses amidst raucous laughter and cheers from the crowd that enveloped them.

As silent witness to this earthly drama, a flicker of what I recognized as hope ran up my spine. I felt sure that John Wheeler was out there, somewhere, rooting for us.

1 Response

Barry Spinello

7 Months AgoMore About Putnam ’46 *60

Peter Putnam ’46 *60, one of Wheeler’s students, is mentioned in the short story. More about Putnam can be found at peterputnam.org and in the Princeton Alumni Weekly of May 5, 1991.