Frank Biondi ’66 and Jane Biondi Munna ’00 Share Lessons from the Life of an Entertainment CEO

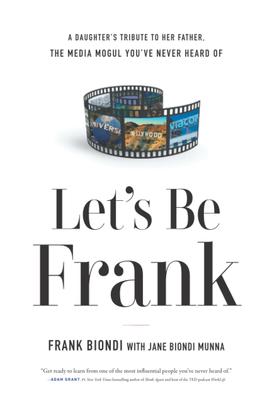

The book: When Frank Biondi died in 2019, newspapers reported his decades of significant (and largely unknown) influence on the entertainment world. Now, daughter Jane Biondi Munna has released Let's Be Frank: A Daughter's Tribute to Her Father, The Media Mogul You've Never Heard Of (River Grove Books), a book that began in the last years of her father’s life as he battled stage-four cancer. Combining firsthand accounts from Biondi’s life with commentary and interviews compiled by Munna, Let’s Be Frank portrays a man with uncommon kindness, integrity, and character leading an industry where these values are often strained. A shrewd businessman and thoughtful leader, Munna tells us, Biondi is someone we should emulate when navigating the challenges and opportunities that life sends our way.

The author: Frank Joseph Biondi Jr. ’66 was an American businessman and entertainment executive who held executive roles at Viacom, Universal Pictures, and HBO. Over a forty-year career spanning from the late 1960s into the 2000s, Biondi served as one of the most prolific CEOs in media. He earned an A.B. in psychology from Princeton and an MBA from Harvard Business School. Biondi passed away in 2019, and is survived by his wife, three children, and six grandchildren.

Jane Biondi Munna ’00 is a managing director at JPMorgan Chase. She has been involved in finance, marketing, strategy and communications roles there for over a decade. She’s also experienced in media and sports — notably, several years spent behind the scenes of Major League Baseball. She earned an MBA from the UCLA Anderson School of Management and an A.B. in economics from Princeton.

Excerpt:

My wife, Carol, is very active in dealing with children who are in the child welfare system and the juvenile justice system. In the course of that work, she bumped into a young man who was also helping kids who were incarcerated. The young man’s name was Scott Budnick, who happened to work at Warner Bros. as a producer.

So we would all socialize from time to time. One day I said to Scott, just to make conversation, “What’s your next movie?”

“Well, we’re doing a comedy in Las Vegas.”

“What’s it about?” I asked.

“It’s kind of complicated,” he said.

“Where are you in the process?”

“We’re just setting up. We won’t start for several months.”

Now at the time—the mid-2000s—I sat on the board of Harrah’s, which ultimately was renamed to Caesars Entertainment.

“Where are you guys going to stay?” I asked Scott.

“I don’t know.”

“Would you be interested in staying at Caesars, or one of the other Harrah’s hotels?”

“Sure, if we can work it out!”

I said, “Let me give the president of Caesars a call.”

So I called up the president of Caesars and put the two of them in touch. They were able to make the arrangements and logistics work, and Scott’s team stayed in the hotel for three or four months while shooting the film in Vegas.

What I didn’t know at the time was that the movie Scott was working on was The Hangover.

. . .

That’s how my father, Frank Biondi, tells the story of how The Hangover came to be made at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. It’s a very Frank story: Dad understates his importance to this story and downplays the significance of his role.

Scott Budnick himself sets the record straight. “I told Frank that we were going to shoot The Hangover in Vegas, but we had been denied by The Wynn. We had been denied by Sheldon Adelson [former CEO of The Sands, which also owned The Venetian]. And I think we had just been denied by the MGM group,” says Scott. “Literally, it was all hopes for Caesars Palace. And I didn’t go in there with an agenda. I didn’t know Frank was on the Caesars Board.”

It’s possible that The Hangover doesn’t end up as the movie it became without the green light from Caesars, and clearly the hotel was crucial to its success. “I mean, it was a character in the film,” says Scott. “It was as important as our actors. It was the film. And that’s why you see it now as one of the hottest hotels in all of Vegas.”

Thanks to the hook-up from my father, says Scott, Caesars gave them unfettered access, which allowed them to pursue their zaniest of comedic stunts. “No matter what we wanted to do, they would always find a way to get to a yes,” Scott says, even if it’s “crazier shit after crazier shit” like “Mike Tyson knocking them out in a suite.”

The MGMs of the world said no. Thanks to my father paying it forward, Caesars said yes. And as you’ll see throughout this book, his minor but crucial involvement had an outsized impact on millions of people who would never know his name.

The Investment Banker Who Became a Hollywood Mogul

I suppose that every little girl grows up admiring her father and learning from his lessons. I know I did. I was his youngest daughter and he called me Janie, or Jane-O. He taught me things that all dads teach their daughters—basic fairness, right and wrong, how to catch a fly ball. (Dad played baseball in college, and still holds a spot in Princeton’s record books for stolen bases in a season and a game.)

As a child, I didn’t know what, exactly, he did when he went to work, but I could understand that he worked with Big Bird and Snuffleupagus at the Children’s Television Workshop, he brought home green slime from Nickelodeon, and we went to the MTV Video Music Awards twenty-five years ago, before it was a phenomenon. I knew he did something with numbers (later learning he started out as an investment banker). For most of my upbringing, I thought the things my father did at work—and the lessons he taught me—were commonplace. Every kid learns this stuff. Every dad’s job is special in some way.

I would eventually realize that my father’s job was highly unusual, and the lessons he taught me were not commonplace in corporate America. Not everyone’s dad had been the CEO of HBO, Universal Studios, and Viacom—which also put him in charge of Paramount, MTV, Nickelodeon, Blockbuster, and Simon & Schuster. Not everyone’s dad served on twenty corporate boards, from The Bank of New York and Vail Resorts to Hasbro, StubHub, Cablevision, and Madison Square Garden.

And as I grew older, I began to sense the enormous impact my father had on the media industry. In the ’80s, at HBO, he had a belief that certain customers would be willing to pay for quality entertainment content. At the time that was hard to believe, almost heretical, but now it’s a foundation of the economic model for television, movies, and even social media and digital platforms. I like to joke that my dad was like the Forrest Gump of media—but with smarts and agency—in that he seemed to be a part of every major media development in the early ’80s into the ’90s—from the consolidation of media conglomerates, to the supremacy of content and the rise and fall of Blockbuster, even serving at the helm of the company that released, well, Forrest Gump and many other memorable and important movies.

I had a unique vantage point to witness how my father helped shape the modern entertainment industry. He was modest and never went out of his way to drop names, but he rubbed shoulders with many famous people during his career both inside and outside the entertainment industry. Over the years, he would tell us stories such as how he played tennis against Donald Trump . . . and how his shot literally knocked Trump down to win the match (more on this in chapter 9). He worked directly with people like billionaire media mogul Sumner Redstone, Carl Icahn, Barry Diller, Don King, Alan Horn, Rob Reiner, daytime television icon Merv Griffin, and Lord of the Rings director Peter Jackson.

Telling the Untold Stories

Dad had many stories about his experiences from his career, and I was surprised throughout my life that very few of them were in the press. The reason was simple—my father was all substance, no flair, and he stayed out of the spotlight. Yet the insiders knew that he launched careers, brokered deals behind the scenes, and quietly made things happen.

When Dad told these stories, people always told him, “You should write a book!” His response was always the same. “When Sumner [Redstone] dies.” As you’ll see in later chapters, Dad had conflicting feelings about Redstone, who both hired and fired him. Dad was grateful for the life-changing opportunity Redstone gave him, but angry and resentful (though secretly relieved!) about how he was let go. The stories about Redstone in this book are some of the few that reflect poorly on the people mentioned, because of my father’s low opinion of Redstone’s character.

Dad’s vow to wait changed in 2018. He had fought many battles in his life, and won most of them, but then he faced an adversary stronger than he had ever faced before: cancer. And as he faced his mortality, he opened up in a way he hadn’t before. And he began writing a book to share his stories and the principles that led to his success. He was committed to making this book happen, so throughout his treatments he would sit down and let me record him telling the stories he wanted to include.

“My first encounter with serendipity was my senior year in high school,” he began one day, sharing a story about how he ended up attending Princeton. We first started recording ten days after a major surgery he underwent. He wore a bathrobe, with tubes coming out of multiple places in his body. His kidneys weren’t working. I knew he was physically uncomfortable and at times in pain, but there were moments when he lit up, a gleam in his eye, telling me about the time he met Merv Griffin, or how in the middle of intense and high-stakes negotiations, Alan Schwartz mistook the photo of my sister as his own daughter. (You’ll read more about all these stories later in the book.)

Listening to him tell these stories gave me a peek inside his life before I was born, or when I was too young to have understood his life outside of our home. He would only record the stories if I was there with him, pressing record on the iPad app. I kept trying to show him how to do it, that it was easy. He wasn’t interested. This was something we were doing together and he wanted me there. There were times I traveled to be with him to spend time and record more stories, but he didn’t have the energy or the interest. Most of the time he pushed himself to do it anyway. We had stories to get through, and nobody knew how much time we had left.

Reprinted with permission from Let’s Be Frank by Frank Biondi and Jane Biondi Munna, published by River Grove Books. © 2022 by River Grove Books. All rights reserved.

Reviews:

“A lovely and deserved portrait of Frank Biondi… He became one of my go-to executives as I strove to understand the fast-changing media business. I greatly valued our relationship and his knowledge. Like many in business, he had talent. But he also had something all too rare: decency.” —Ken Auletta, author of Googled

No responses yet