Garry Sparks Is Changing the Way We Think About Religion in the Americas

We typically picture the Spanish invasion of Latin America as one of conquistadors forcing their rule and religion upon Indigenous populations. The moments of first contact in the 1500s, however, were much messier and more interesting, according to religion professor Garry Sparks. Christian missionaries sometimes collaborated alongside Maya elites to translate and interpret religious ideas in a way that has left an indelible impression on Mesoamerican culture.

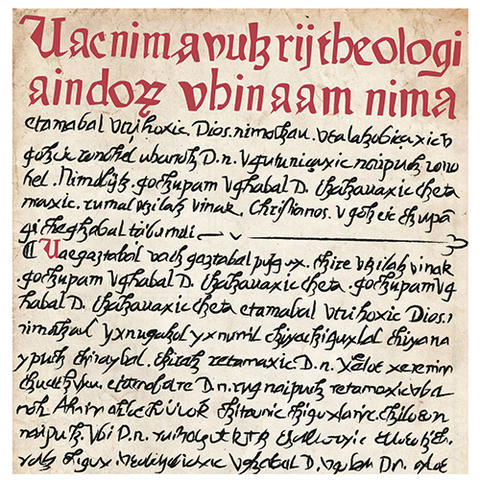

“We have this remarkable paper trail of documents in Native languages of the time,” says Sparks, who draws upon Princeton’s collection of some 300 such manuscripts — one of the largest collections in the world.

Sparks first became interested in Central American culture while volunteering with the influx of refugees from El Salvador and Guatemala when he was a student in Texas in the late 1980s and early 1990s, later spending three years among the Highland Maya in Guatemala. Since earning a doctorate at the University of Chicago, he has dedicated his research to exploring these connections, including co-teaching a two-week summer workshop to bring international, scholars together. “There is a profound ignorance and misunderstanding of Latin American religion today,” he says. “My hope is to get back to cycles of respect, mutuality, solidarity, and constructive engagement.”

Quick Facts

Title

Associate Professor of Religion

Time at Princeton

1 year

Recent Class

Special Topics in the Study of Religion: Inventing “Indians” and “Religion”

2 Responses

Linda Bonder ’85

10 Months AgoHistorical Documents and the Maya People

The March 2025 PAW article “Changing the Way We Think About Religion in the Americas,” about associate professor Garry Sparks, refers to Princeton’s collection of historical documents written in Maya languages. The article does not specify whether these documents are originals, copies, on loan, or owned by the University. Any such original documents are historical artifacts of the Maya people. Those pieces as well as any rare or difficult to reproduce copies should be in the hands of the people whose history they carry.

This situation begs some questions: 1. How did those documents come into Princeton’s possession? and 2. Why do they continue to be in Princeton’s possession when historians worldwide are calling for historical artifacts to be returned to their homelands? Princeton’s own Chika Okeke-Agulu, Nigerian art historian and African art professor, made exactly that case in a 2021 interview published by the CBC and reproduced on the University website. However, the PAW article doesn’t even mention the problem of cultural artifacts maintained by others. Instead, the article seems to brag that Princeton has “one of the largest collections in the world” of these Maya Native language documents, including “nine of the 20 known versions” of one particular tome from the 1550s.

It is admittedly a nontrivial challenge to figure out who exactly should take possession of documents from so long ago. Nevertheless, governments and museums around the world are making the effort to identify more rightful owners and repatriate artifacts. If Princeton’s collection contains anything which cannot be readily found in the Maya’s own repositories, the University needs to step up and return the documents to the Maya people.

Daniel J. Linke, Gabriel Swift

10 Months AgoClarifications from Princeton University Library

The Catholic theology referenced in the letter was written by Spanish Dominican priest Domingo de Vico, one of the first Christian missionaries to the Highland Maya. As there are no surviving copies as written by Vico, Professor Sparks’ research is based on the examination of second or third-generation copies from the late 1500s and beyond.

Princeton University Library (PUL) received these copies, along with most of its Mesoamerican collection, as a gift in 1946 from Robert S. Garrett, Class of 1897, who had purchased them in 1930 from early Mayanist William E. Gates.

PUL works closely with campus leadership to review, on an ongoing basis, issues of provenance and repatriation inherent to its stewardship of numerous significant historical artifacts. The Library also endeavors to empower scholars and students to work closely with these materials. One example of this includes the co-sponsorship of up to eight Mexican and Guatemalan scholars, led by Professor Sparks, for a weeklong on-campus workshop to study, understand, and promote the scholarship of this collection.

Editor’s note: Daniel J. Linke is acting associate university librarian for special collections, and Gabriel Swift is the librarian for Early American collections.