Gender gap at eating clubs; fewer jobs for grad students

If you were a visitor to campus a couple of weeks ago and glanced at a copy of The Daily Princetonian, you might have left with the impression that the eating clubs are still male-only.

The Prince that day contained a full-page call to action on binge-drinking, an ad signed by 10 newly elected eating club presidents and the president of the Undergraduate Student Government (USG).

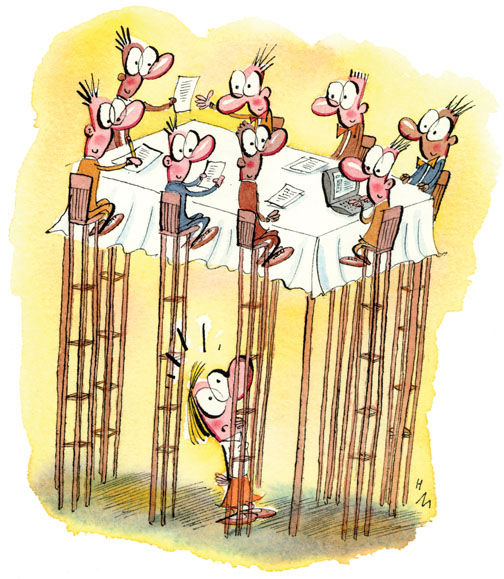

All 11 names were male. “Connor, Chris, Steve, Douglas, Alex ... ” the list read, a visual testament to a rarely discussed topic on campus. Why are there so few female students in positions of power in the clubs, especially when women fill so many of the University’s top administrative positions?

This year’s graduating seniors will have seen no more than five female eating-club presidents during their four years at Princeton — out of a total of 50 positions, more or less. Considering that Cottage, Tiger Inn, and Ivy became co-ed in our lifetimes, perhaps that isn’t so bad.

But consider that seniors will have seen no female presidents or vice presidents of the USG, either. Harvard’s student government has both a female president and vice president this year, as did Yale’s last year.

So, what gives?

Former Tower Club president Stephanie Burset ’09 said women have no extra difficulty once they attain these positions, but she wondered “if there is a sort of orange glass ceiling” when it comes to running for them.

Shortly before her election, she recalled, a club member told her that she thought she’d make a good vice president but wasn’t sure whether people would take her seriously as president because she was a woman.

One theory is that the responsibility of having to deal with intoxicated or belligerent students on weekends scares off women from running. But club members noted that the task actually falls on different officers each night, and there tend to be plenty of women in these cabinet positions.

Sarah Langberg ’09 broke a long trend by running for USG president in 2007, but when she campaigned partly on that very fact, she said, some students accused her of seeking an unfair advantage by “playing the gender card.” (Josh Weinstein ’09 was elected.)

On the other hand, she said she has never heard of a female student who wanted to run for president but was reluctant to do it because of her gender. “It’s not a problem unless women think it’s a problem,” Langberg said.

By Melinda Baldwin GS

This is not a great time to be looking for a job, even in the ivory tower. The New York Times reported in February that 48 percent of universities have imposed at least a partial hiring freeze. Even fields like economics, where Ph.D.s usually are in high demand, have been affected: The Wall Street Journal recently ran an article titled “Job Market for Economists Turns ... Dismal.”

Given the rough economic climate surrounding job hunters, Dean of the Graduate School William Russel said that “responses [about jobs] have been much more positive than I expected.” Even in a downturn, Russel said, the strength of Princeton’s graduate programs tends to put their students at the “high end of the applicant pool.”

Similarly, economics graduate student Ing-Haw Cheng thought that this “was a good year for Princeton in a tough year overall.” Cheng, who has accepted a job at the University of Michigan’s business school, said that many (though not all) of his friends in economics had found positions. But he added that the number of offers was more limited than in previous years; universities that might have hired two or three professors in better years now only wanted one.

Students in other fields also found the market challenging. Dan Bouk, who is finishing a Ph.D. in history, saw a lot of promising openings posted when he began his search, “but many good jobs disappeared as the fall progressed.” The search did end well for Bouk, who will be a professor at Colgate University this fall.

But the same has not been true for all Princeton graduates. One recent Ph.D. in the humanities, who asked not to be named, applied for 30 jobs, but nearly a third of those universities canceled their searches. The remaining applications yielded three interviews but no offers. She plans to start a new search in the fall, though she said she is “really curious to see if there’s going to be a decisive turn [in university hiring].”

No responses yet