For a man who began a career in the Foreign Service almost by chance, and never rose much higher than a midlevel position, George Frost Kennan ’25 had a profound effect on U.S. foreign policy. Best known as the author of the “Containment” doctrine that became the foundation of U.S. policy toward the Soviet Union during the Cold War, Kennan said later that the policy was misunderstood and misapplied. He felt he had “loosened a large boulder from the top of a cliff,” Kennan wrote in his Memoirs (1967), and helplessly witnessed “its path of destruction in the valley below.”

As Kennan approaches his 100th birthday on February 16, 2004, Princeton is exploring the Cold War period and his role in it, in an exhibition at Firestone Library, “the Life and Times of George F. Kennan,” which runs through April 18. U.S. Secretary of State Colin L. Powell will give the keynote address at a conference celebrating Kennan’s life on February 20, 2004.

“While Kennan is not widely known by the general public, his contribution to U.S. history is legend within the diplomatic community,” says University archivist Daniel Linke, a co-organizer of the exhibition.

In his Memoirs, Kennan, who grew up in Wisconsin, says he decided to enter the Foreign Service because he had the “feeling that I did not know what else to do.” After passing the exams, he was sent to various posts in Europe, and in 1928 undertook special training in Russian affairs in Berlin.

He was 29 when he first went to Moscow in 1933; over the next 20 years, serving in various foreign-service positions there and in other cities, he would come to know the Soviets well.

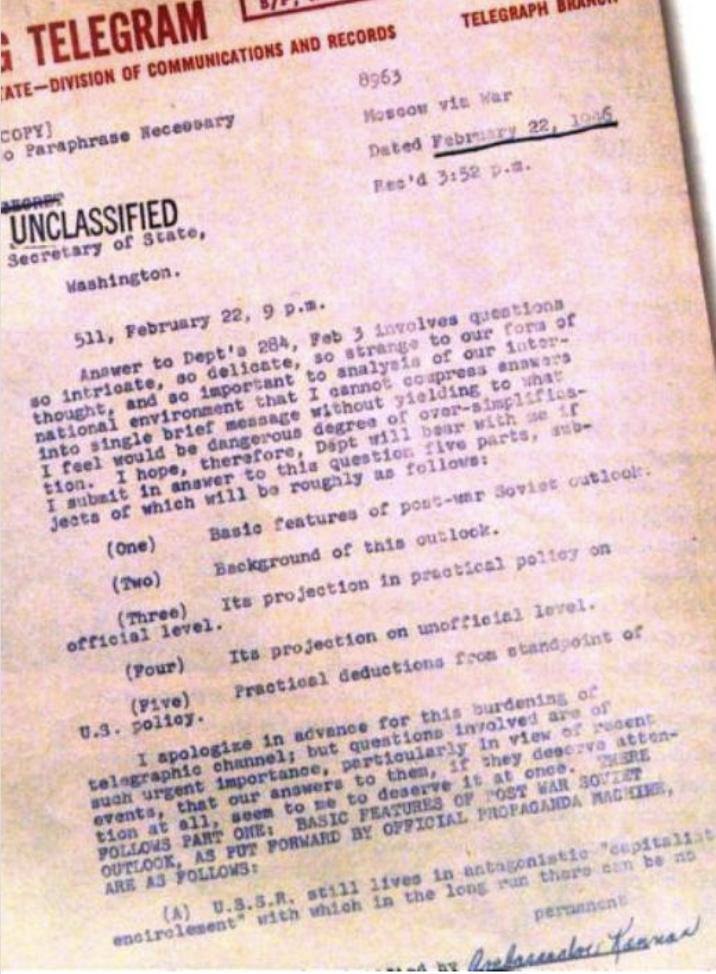

In 1946, at age 42, Kennan sent what has come to be known as the “Long Telegram” to the State Department. In the 8,000-word, 18-page telegram, on display in Firestone’s main gallery, Kennan wrote that Joseph Stalin’s regime was a “political force committed fanatically to the belief that with the U.S. there can be no permanent modus vivendi, that it is desirable and necessary that the internal harmony of our society be disrupted, our traditional way of life be destroyed, the international authority of our state be broken.”

He continued his analysis, arguing that the Soviet challenge was “within our power to solve – and without recourse to any general military conflict.” The telegram ended with an exhortation: “…the greatest danger that can befall us in coping with this problem of Soviet communism, is that we shall allow ourselves to become like those with whom we are coping.”

In July 1947, with the Cold War a reality, Kennan wrote an anonymous article for Foreign Affairs magazine, “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” by “X,” which was based on the Long Telegram and outlined a strategy for dealing with the Soviet Union. The word “containment” appeared in the article three times, and a political doctrine was born. While Kennan had argued for a nuanced policy of a “long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies,” his argument was interpreted in far blunter ways, which caused Kennan much regret. He later wrote that he had intended the article to be a plea that war was not inevitable, and that there was “a middle ground of political resistance on which we could stand with reasonable prospect of success.”

Princeton history professor Stephen Kotkin, director of the University’s Russian studies program, calls Kennan “a rare statesman-scholar. He understood very early on, and ably explained to policymakers and the public, the imperative to stand up to Communism. He also warned, in battling the Communists, not to become like them, not to adopt their methods, not to compromise our institutions and our freedoms in the necessary Cold War struggle.”

In addition to the Long Telegram and the Foreign Affairs article, the exhibit at Firestone includes poems Kennan wrote as a teenager, an early Princeton report card, and photographs, letters, diary entries, and memos prepared during Kennan’s time at Princeton and throughout his career. The material was drawn from 20 collections at the University, said Linke, including Kennan’s own papers and those of former Secretary of Defense James Forrestal ’15, and former Secretaries of State Robert Lansing and John Foster Dulles ’08. Kennan gave his papers to the University in 1968; while many are already available to researchers, some will be opened only after his death.

“As a diplomat, Kennan is most remembered for the Long Telegram,” says Jack F. Matlock, former U.S. ambassador to the U.S.S.R. and a lecturer at the Woodrow Wilson School but “no less important was his contribution to the Marshall Plan, which he helped draft as head of the State Department’s policy-planning staff.” Matlock also cites Kennan’s written work, including his memoirs, as major contributions to understanding 20th-century diplomacy.

Matlock is a participant in the conference, which will bring together scholars, journalists, and diplomats who served during the Cold War or at its end, or are working in diplomacy today. Other expected speakers include Robert Tucker, professor emeritus of politics and a specialist in Soviet affairs; Joseph Nye ’58, dean of the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard; Kennan’s biographer, John Lewis Gaddis; and journalist Don Oberdorfer ’52. Like Matlock, Oberdorfer lauds Kennan as a critic and writer. “His extensive writings in memoirs, other books and articles, and periodic public testimony were seriously regarded for decades by both sides in foreign policy debates, especially those of the Cold War. An important part of the story was his great skill as a writer of the English language,” he says.

Kennan, who still lives in Princeton, continues to keep abreast of world events. In a New Yorker magazine interview October 14, 2002, he told writer Jane Mayer that he saw grave peril and little justification for the Bush administration’s proposed pre-emptive strike on Iraq. And in a letter to the editor of the Washington Post on March 25, 2003, Kennan wrote, “I am extremely concerned about the shameful, almost totally passivity of Congress during the period of preparations for our military attack on Iraq. Congress’s inaction is a dangerous precedent in executive-legislative relations. In light of this precedent, future presidents will be tempted to seize virtually dictatorial powers under the title of commander-in-chief, and nothing in our history rules out the possibility of their yielding to that temptation. This seems to be the meaning of the recent crisis.”

This was originally published in the Dec. 17, 2003, issue of PAW.

No responses yet