Geosciences: Feeling the Heat

Study finds climate change will only exacerbate inequality in the United States

By now, the scientific community overwhelmingly agrees that Earth is warming — climate models predict a national rise in temperature in the U.S. of between 2 and 7 degrees Celsius over the next 100 years. What’s harder to gauge is how that rise will affect citizens in their own backyards. “No one lives at the national level — people live at the local level,” says Bob Kopp, a climate scientist at Rutgers University-New Brunswick who is a former Princeton postdoc. “If you look at the impacts at too aggregated a scale, you miss a lot of the story.”

Kopp is part of a research team — including Princeton geosciences and public policy professor Michael Oppenheimer, Woodrow Wilson School doctoral student DJ Rasmussen, and University of California, Berkeley professor and former Princeton postdoc Solomon Hsiang — that has developed a prognosis of how climate change is likely to affect the country on a local level. In a paper published in Science in June, they and their eight additional collaborators found a huge discrepancy in the effects of climate change on economic activity depending on where people live.

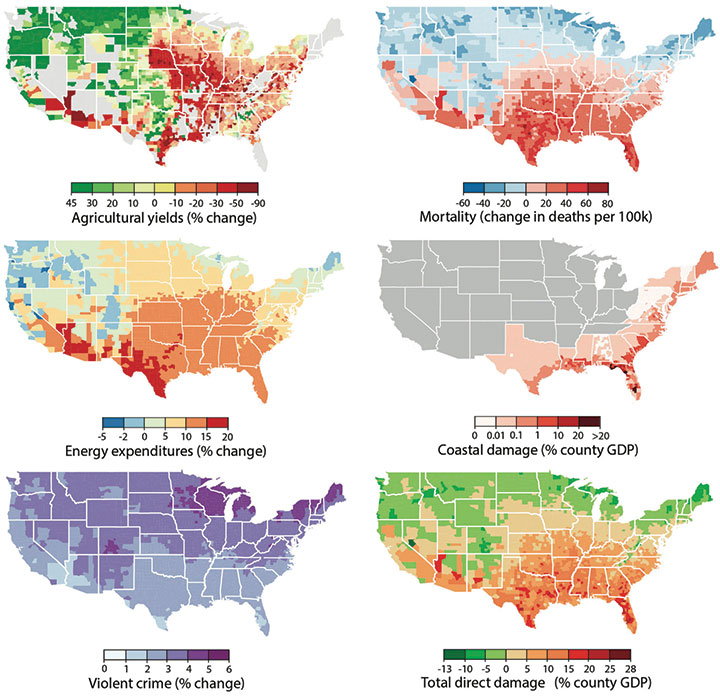

They examined impacts such as heat- and cold-related deaths, the ability of people to work in the heat, crop yields, energy demand, coastal storms, and crime. While some areas, including the far North and parts of the Rockies, might not experience much net harm — or may even benefit from modestly higher temperatures — areas in the South are especially at risk.

As a result, economic inequality between regions will worsen. “Places that are already warm will be harmed much more than places that are cooler,” Kopp says. “Those warmer places also coincidentally tend to be places that are already poorer, so the net effect will be a transfer of wealth from South to North and from the poorer to the wealthier.”

The paper takes advantage of econometric research that has emerged in the last decade to create detailed information on the effects of weather patterns on economic activity. “In the past decade, there has been an explosion of research that has allowed us to leverage new sources of information,” says Rasmussen, who analyzed much of the climate data. By using cloud computing capable of handling vast quantities of data, the researchers crunched the numbers on a county-by-county basis across the country to drill down to localized effects.

Some areas, such as northern Michigan and Maine, could experience the equivalent of more than a 10 percent increase in gross domestic product (GDP), due to fewer deaths from cold weather, lower energy costs, and longer growing seasons. Areas in the southeastern states, meanwhile, could see equivalent losses of 25 percent of GDP or more. Those losses are almost entirely driven by increases in temperature, the researchers found. Despite fallout from high-profile weather events such as Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, those hardships pale in comparison to the effects of excess heat at a national scale. “The silent killer is the increase in temperature,” Rasmussen says, explaining that hotter temperatures will cause crops to wither, violent crime to increase, and people to die from heat exposure.

One thing the study doesn’t measure, however, is how people will respond to such changes in the climate — whether they’ll move from region to region, for example, or find other new ways to adapt. While ultimately the best way to mitigate these economic effects is to reduce greenhouse gases that cause climate change, the authors hope that the county-by-county data in the report will help local policymakers take preventative measures to adapt.

Decision-makers in coastal communities such as Miami, for example, could enact building codes that adapt to storm surges by providing incentives to build in different places, or elevating buildings, or adding protective structures. In other cases, communities could change the crop mix or add irrigation to combat decreases in crop yields, or install community cooling centers to stave off health effects of heat waves. “It’s no longer enough to just look at the past to decide on changes for the future,” says Rasmussen. “Our hope is that this information will give people what they need to think about what is coming down the road, and make changes now that will lower the economic cost of climate change.”

For a county-by-county projection of how local economies will be affected, go to http://bit.ly/climatedamage

3 Responses

F. Paul Brady *60

8 Years AgoNumbers Don’t Point to a Climate Crisis

Published online Jan. 4, 2018

Global warming is no hoax, but neither does it portend a climate crisis! PAW’s article (“Feeling the Heat,” Life of the Mind, Nov. 8) asserts that “climate models predict a national rise in temperature of between 2 and 7 degrees Celsius over the next 100 years.” However, climate models have been shown to exaggerate global warming by factors between 2 and 3! Real-world measurements show that since about 1950, when carbon emissions began to increase rapidly — averaging at least 2 percent per year — the global surface temperatures have increased on average about 0.12 C per decade or 1.2 C in 100 years. Why do scientists and the media continue to use the above alarmist model predictions?

Please see the climate establishment’s UN IPCC’s Climate Change 2014 Summary, etc., page 3, Figure SPM.1, panels (a) and (d ), showing the increases in global-temperature rise and CO2 emissions.

There are also several analyses of satellite data showing similar moderate rates of temperature increase — data available since 1979. Professor John Christy summarized these in a presentation to the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, and compared them to climate models, showing the large over-warming they predicted! The link to his House report is:

https://science.house.gov/sites/republicans.science.house.gov/files/documents/HHRG-114-SY-WState-JChristy-20160202.pdf

The UN’s IPCC reports never compare their model predictions to the real-world measurements of global temperature change, but always merely quote the alarmist (and wrong) model predictions.

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoWhy are those who doubt...

Why are those who doubt global warming so ferocious in presenting their views? All I can think of is that they fear that capitalism will suffer. If capitalism destroys our lives and welfare, perhaps it should be destroyed. I think perhaps fear of losing dividends is the motive here.

Rick Mott ’73

7 Years AgoFeynman Had the Right Attitude

"Ferocious" is hardly the right word. I was trained as an engineer. We use models all the time, but only in well-characterized problem domains where careful experimental evidence validates them. Climate doesn't meet either condition.

The Feynman quote which applies here is "no matter how pretty it is, no matter who said it, if doesn't agree with experiment, it's wrong." The models are not able to replicate the results from two significant experimental datasets: satellite global temperatures and radiosonde weather balloons. Their history is not long, but long enough to be convincing to me. So yes, the more extreme upper end of the climate model outputs is just silly at this point.