Say what you will about him, but Satan knows how to work a room.

On a warm evening in May, he makes his way through the green neon glow at Rooster’s Blues House in Oxford, Miss., and the crowd welcomes him like royalty. It’s a crowded, second-floor bar on the town square, the kind of place that still has a cigarette machine. Satan accepts compliments and pats on the back, shaking every hand with a respectful, “Thank you, sir.” Walking a step or two behind him is Adam, his longtime sideman, partner, and acolyte. Satan and Adam: the fallen angel and the first man. They will be signing autographs in the back.

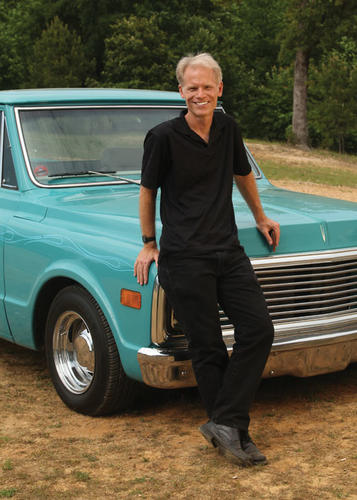

Satan — Mr. Satan to you and me — is Sterling Magee, a guitarist, backup player for musicians from James Brown to George Benson, and one-man band. And practically a force of nature — which you’d know if you spent any time around him in the old days. Adam is Adam Gussow ’79 *00, who leads something of a double life as an associate professor of English and Southern studies at the University of Mississippi by day and one of the best blues-harmonica players in the world — whenever time permits. The gathering at Rooster’s is a launch party for the duo’s new CD, Back in the Game, their first recorded collaboration in 13 years. It also happens to be Mr. Satan’s 75th birthday.

Magee crosses Rooster’s with a shuffle as Gussow hovers like an attentive son. In their brief time on stage, Magee shows he still can play a mean guitar, and his rasping voice retains much of its old force. As he used to do when the two were sidewalk regulars on 125th Street in Harlem back in the ’80s and early ’90s, Gussow is by Mr. Satan’s side, hands and harmonica cupped over his microphone, eyes closed, bobbing and jumping, feeling it as they jam on the blues song “Big Boss Man.”

Twelve hours later, Gussow and Magee meet up again in blinding sunlight at the opening of an event called Hill Country Harmonica. Gussow is the organizer and driving force behind what the psychedelic posters bill as “A North Mississippi Blues Harp Homecoming.” It is a festival/conference/seminar/jamboree held on a ranch about 20 miles north of Oxford. In this, its second year, Hill Country Harmonica has drawn more than 140 participants from 36 states and as far away as Russia, along with a documentary film crew and a blogger for The Huffington Post. Everyone sits at picnic benches in what is essentially a huge, open-walled shed, with a concession stand along one side and a stage at the end. For two days they will eat and play here, most of them sleeping in tents pitched out in the surrounding fields.

It’s a blues-harmonica Woodstock, although a lot more organized than the prototype. There are lectures each day as well as breakout sessions on everything from “tone and tongue blocking” to “soloing over 1st and 3rd positions,” plus evening concerts and almost unlimited jam time. On the first day, Satan and Adam are lecturing about being buskers — street musicians — and then playing a set that night. If you want to learn the finer points of the four-hole draw or simply listen to some of the best blues going, this is the place to be.

After 25 years together, the affection and respect that Satan and Adam have for one another is undimmed. “He’s a No. 1 guy in my book. That’s the best I can say about him,” says Magee, who is otherwise a man of few words. Then he adds slyly, “At least look who he’s playing with.” Gussow returns the compliments, addressing Magee as “gentleman and genius.”

For a tiny instrument, the harmonica has a lot of nicknames — harp, mouth organ, whistle, even Mississippi saxophone — all of which are used interchangeably. Because harmonicas are tuned to a particular key, most good players travel with harps in a range of keys, carrying them in a small attaché case. The more flamboyant stud their harps on bandoliers worn across the chest. It provides a rakish look.

More than any other form of American music, the blues is steeped in romance. Perhaps the most romantic blues legend of all is of the time Mississippi blues great Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil at a crossroads at midnight in exchange for a demonic ability to play guitar. Adam Gussow never sold his soul to the devil, and considering that he is a half-Jewish white academic from suburban New York who bears a striking resemblance to the actor Ed Begley Jr., one could be forgiven for saying that any overlaps with Johnson are rough at best. But given that he partnered for so long with a man who calls himself Satan, it is not surprising that he has made an academic career of exploring, explaining, and to a certain extent exploding that old romantic trope. Gussow himself now stands at the contemporary blues crossroads where race, history, and the future of the genre meet.

Satan and Adam met in New York in October 1986. Satan — Magee — was playing solo in front of the telephone company office on 125th Street, and Gussow, who was passing by in a car, rolled down the window to listen. Magee’s electric guitar, Gussow later wrote, produced “withering flurries of bittersweet chords,” supplemented by a unique percussion contraption Magee had cobbled together from a hi-hat cymbal, a maraca, and a tambourine, which he controlled with his foot. Gussow pulled over and asked who was making that amazing sound.

“Who, him?” a friend replied. “That’s Satan.”

Gussow was transfixed. “He was Robert Johnson reborn as Parliament Funkadelic, a Mississippi flood roaring down Broadway,” he recalled. The next day, Gussow returned with his harps and a small amplifier, and asked if he could sit in. Magee flashed “a gold-toothed grin,” Gussow says, “and roared, ‘Come on up!’” Over a period of several weeks, they began playing together regularly — sometimes with others, sometimes alone. Before long, Magee told Gussow with amusement, people on the street were asking, “Hey, Satan, where’s that white boy at?” Magee’s friends told Gussow that his presence pushed Magee to play harder.

Gussow had taught himself harmonica in high school, working his way through everything from Homesick James to the J. Geils Band, and he continued to play at Princeton in a band called Spiral. He stopped in the years after graduation, when he moved briefly to California and later worked at a New York literary agency. It took a romantic breakup in 1983 to drive him back to his harps. “I had the blues,” he admits. “It sounds clichéd, but it’s true.” He dropped out of a Ph.D. program at Columbia and went to Paris, where he began performing in the subways to make money. After his return to New York a few months later, Gussow worked at temp jobs, played in clubs and occasionally on the streets, and studied with blues-harmonica master Nat Riddles before meeting Magee.

During their first several years together in the mid-1980s, Gussow and Magee would play several days a week when the weather was good. Their repertoire included everything from classics such as “C.C. Rider” and “Sweet Home Chicago” to Magee’s original compositions. They were playing one of those compositions, “Freedom for My People,” in the summer of 1987 when Bono and the other members of U2 walked by. The U2 musicians were in Harlem filming their concert documentary, Rattle and Hum, and liked what they heard. A 39-second clip of the duo made it into the film.

Gussow and Magee never practiced, and they played whatever they were in the mood to play — never exactly the same way twice. “He played,” Gussow wrote later in his 1998 memoir, Mr. Satan’s Apprentice: A Blues Memoir (Pantheon), “I kept up, provoking his genius. Since he was liable to take off in any direction, I was forced to go for broke as a matter of principle, shrugging off train wrecks as an occupational hazard. The groove was our one constant, the foundation of all musical sympathy: From the very first, we’d attacked the beat the same way.”

As in any band, there were occasional squabbles about money, and Gussow learned to accept some of Magee’s rather original ideas about dates on which the world was going to end, referring to it as “Mr. Satan’s Annual Countdown to Apocalypse.” Over time, he also learned about Magee’s past.

The man known as Mr. Satan was raised in rural Mississippi and Florida in a very religious family. After a stint as an Army paratrooper in Germany, he became a well-respected guitarist known as “Five Fingers Magee” and recorded a few albums on Ray Charles’ record label. He also became a session musician for many of the big names who came through Harlem.

In the late 1970s, after his wife died of cancer, a deeply embittered Magee — rather than sell his soul to the devil — seems to have spat in God’s eye. The story as he has told it over the years is somewhat fragmentary. In one account, he was playing in Florida when a woman complimented him by saying that he played so well he needed to be born again. “I went off on the woman,” Magee told an interviewer. “I said, ‘I’m already born again. I’m Satan.’” That is how he insisted on being called when they met, Gussow recalls. Magee always referred to Gussow as “Mr. Adam,” and so came to adopt the honorific, “Mr. Satan,” for himself.

It was not always easy for a white harpist to be accepted as a bluesman on the streets of Harlem. Gussow acknowledges that although audiences sometimes viewed him skeptically, he usually won them over on the strength of his playing. But there were tensions, particularly during the fragile months after three African-American teenagers were attacked by several white men at Howard Beach in late 1986. On the few occasions then and later when anyone would question whether a white musician had any business playing blues in a black neighborhood, Magee angrily leapt to his defense.

At the end of each performing day, the pair would divide the money in their tip bucket. But busking, Gussow admits, was a poor way of paying the bills. Late in 1987, he received a professional and financial boost when he was asked to join the road company of Big River, a musical adaptation of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Magee went back to playing alone.

When Gussow returned to New York several months later, Satan and Adam, as they now billed themselves, began to add occasional club engagements and tour dates. In 1991, they opened for Bo Diddley on a tour of Great Britain and soon afterward released two albums, Harlem Blues and Mother Mojo, both critical successes. “I don’t know where you found these guys,” blues promoter Quint Davis told their agent, “but I’m gonna make them stars.”

Joint stardom never quite materialized. Gussow began to pursue his Ph.D. in English at Princeton, and Magee moved to Virginia, both of them commuting to New York on weekends to play together. In the spring of 1998, however, Magee suffered a nervous breakdown. Gussow learned that he had been committed to a psychiatric hospital, temporarily renouncing the name Satan and demanding to be called Sterling again. After his release, the two limped along for several more months before Magee disappeared altogether. Gussow eventually learned that Magee had suffered another breakdown and lost touch with him until a documentary filmmaker located Magee several years later, living in a Florida nursing home. Mr. Satan no longer could play a note on the guitar, though he and his guitar skills since have been nursed back to health (his guitar skills are not what they once were). Gussow, meanwhile, accepted the dissolution of the duo. “We were,” he says, “dead and gone, in showbiz terms.”

For the next several years, Gussow turned his attention entirely toward academics. After earning his doctorate in 2000, he joined the Ole Miss faculty in 2002, where he teaches about American and African-American literature, Southern autobiography, and the role of race in American culture. It is, he says, “the perfect job for me.” He has written three books, including his memoir and Seems Like Murder: Southern Violence and the Blues Tradition (University of Chicago Press, 2002), which won the Holman Award from the Society for the Study of Southern Literature.

As a member of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at Ole Miss, Gussow organized the Blues Today Symposium, which he describes as a dialogue among academics, performers, record producers, DJs, and journalists. He himself moves among several camps. “To play before an almost entirely black audience on the street in a place like Harlem is an experience that almost nobody [white] has had,” he says. But he also has gone back and forth between practice and theory, between making music and thinking, writing, and talking about it: “That really is how I live my life. I don’t want to do one or the other.”

He has continued to do both. Gussow and Magee reunited in 2005 and have played together several times in the years since then, culminating in their new album. Gussow resumed his own performing career and released his first solo album, Kick and Stomp, in 2010. He also runs the website Modern Blues Harmonica (www.modernbluesharmonica.com), which contains — among other things — links to Gussow’s upcoming performances, information about the harmonica and the music it makes, and links for those who wish to purchase video lessons.

Gussow embraces a view of the blues harp that honors the old styles but strives to prevent the blues from falling into a nostalgia-driven stasis. He conceived of Hill Country Harmonica to make “a space for a dialogue between the traditional and the more modern stuff,” he explains.

It was not possible to avoid noticing that, while about half the performers at Hill Country Harmonica were black, the registrants were almost entirely white (and predominantly male). There were lots of porkpie hats and baseball caps, salt-and-pepper goatees and soul patches. The vibe didn’t say: “Delta juke joint.” It said: “Cialis commercial.”

When asked why more young African-Americans don’t seem to listen to the blues, Gussow begins defensively by turning the question on its head. “Why don’t young white people go for Frank Sinatra music?” he asks. “If a whole lot of worried black people sat around asking that question, it would sound ridiculous. [It’s] because they’re kids, and they like different stuff than their parents.”

But there is, he acknowledges, more to it than that, some of which he is exploring in a book he is writing about the origins of satanic imagery in the blues. He traces those origins to some of the earliest blues recordings, made just after World War I. The great agricultural depression of the 1920s perfectly coincided with Prohibition, the advent of long-playing records and jukeboxes, and the beginnings of the African-American migration to the industrial North, all of which dramatically altered traditional black communities in the rural South. Black preachers railed against the wild, rootless, disrespectful younger generation, and it was there, in the pulpit, Gussow argues, that the blues first became known as the devil’s music. Robert Johnson and other young blues performers, Gussow says, embraced this imagery as a way of thumbing their noses at their elders.

“If you wanted to tweak the sensibilities of black religious folk, as blues players often did,” Gussow believes, nothing would be more effective than wrapping your arm around the devil. “You’re saying basically, ‘I’m bad, baby; I don’t care who knows it.’”

What one generation finds daring, though, its children often find boring. By the 1960s, many younger African-Americans had moved away from the blues to other forms of music. It was, however, a short aesthetic trip for young whites to move from folk music to the blues as another “authentic” roots sound. Listening to the blues also helped them ally themselves, during the civil-rights movement, with the downtrodden. By the late ’60s, Muddy Waters observed in his memoirs, he had been embraced by white audiences while his younger black fans mostly had disappeared.

As Gussow sees it, this perceived need to stay true to the music’s roots has led many blues performers to stagnate. He singles out contemporary white blues harpists such as Kim Wilson, Rod Piazza, and Rick Estrin, saying that, by trying too hard to emulate the old blues masters, they have perpetuated an unduly conservative approach to what ought to be a more vital and evolving kind of music. “It has been costumed [and] profoundly confected onto that old-time stuff like it’s the only way to go,” he says. “They resist modernization.”

If many modern blues musicians are content to emulate Little Walter, Muddy Waters, and their other artistic fathers, Gussow believes that his own black mentor saved him from following the same well-trodden path. Magee, he says, “played stuff that was so new that I couldn’t get away with playing the old stuff. And he constantly gave me that lesson: Be you. Sterling’s example freed me to try to do my own thing.” Gussow is particularly proud that the song on his new solo album that has been getting the most airplay is a cover of “Sunshine of Your Love,” co-written by Eric Clapton and performed by the 1960s rock group Cream. The piece is “real blues,” says Gussow. Playing it is “a way in which I’m honoring Sterling’s gift to me — that gift to be original. I’m doing the blues of my time, and I’m responding creatively to it.”

The professionals who performed at Hill Country Harmonica covered a broad spectrum of modern blues harmonica styles and sounds. They included Hill Country legend Bill “Howl-N-Madd” Perry; 20-year-old Brandon Bailey; Sonny Boy Terry and his zydeco sound from Houston; Deak Harp, a protégé of the legendary James Cotton; and Jason Ricci, a young Keith Richards look-alike who played an otherworldly synthesized improvisation in which his harmonica produced sounds like a steel drum. And, of course, there were Satan and Adam on stage again.

The culmination of both nights at Hill Country Harmonica was an open jam session. Saturday’s headliner was the Grammy-winning Sugar Blue and his band. After their set, band members remained on stage, and audience members were invited to come up and play for a minute or two with one of the best blues groups in the world. Amateur harpists quickly lined up 30 and 40 deep, hunched over their instruments as they waited their turn, practicing their licks.

After a while, a bottle or two of corn whiskey appeared from somewhere and were passed surreptitiously around the picnic tables. Eleven turned into midnight, which turned into 1 a.m. Even Satan had gone off to bed.

Into the small hours of the morning, Sugar Blue jammed on, as Gussow smiled at his handiwork and a long line of aspiring bluesmen stretched out into the Mississippi night.

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

No responses yet