The Giving Plea

Princeton is raising more money than ever, yet participation rates are declining. What gives when it comes to Annual Giving?

For the past few years, over Fourth of July weekend, Peter Ryan ’07 and his father, Tom, have gotten together on Cape Cod for family bonding and some good-natured one-upsmanship. The annual giving campaigns at Princeton and Holy Cross, Tom’s alma mater, close on June 30 and that is a big deal in the Ryan family. Both men are longtime giving chairs for their respective classes; Tom, in fact, once served as the Crusaders’ development director. So, to make things a little more, you know, interesting before the final numbers come out, they place a friendly wager: Whoever’s class had the lower participation rate that year pays for breakfast.

Holy Cross alums are famous for their loyalty, but Peter wins the bet more often than not. The commitment of its alumni makes Princeton the envy of other colleges. But lately, both Ryans have been concerned. Whether they have cause to feel that way depends on how one looks at annual giving. Princeton set another record last year, raising a whopping $81.8 million, $13 million more than it raised in 2021. Except for occasional dips, such as during the 2008 recession, the total dollar amount raised by the University has been on a steady upward trajectory.

To see a glass half empty, though, look at the participation rate, which has been moving in a different direction. Consider a few examples:

- As recently as 2015, more than 60% of Princeton’s undergraduate alumni supported the Annual Giving campaign, but that number has fallen in seven out of the past eight years and has not cracked 50% since 2019.

- Over the past 15 years, Peter Ryan’s Class of 2007 has seen its participation rate drop from 75% to 62%, even though last year was a major reunion for the class.

- Fifty-two percent of the Class of 2018 gave when its members graduated, but only 30% gave in 2022.

- Taking a longer view, the five youngest classes gave at an average rate of 58% in 2000 but only 31% last year.

“We’re looking at a phenomenon that’s not a Princeton-specific phenomenon, and I think we have to keep that in mind as we try to understand it and respond to it,” President Christopher Eisgruber ’83 told PAW in March. “But we do want to understand and respond to it in a strong way.” (Up at Holy Cross, Tom Ryan’s Class of ’76 fell below 60% participation last year for the first time. “That killed me,” he says.)

Though the Annual Giving office, part of University Advancement, has a paid staff of 25 and provides critical support, Princeton’s AG campaigns are driven by more than 3,000 alumni volunteers, usually classmates contacting fellow classmates asking, can you at least give something. Though many make larger gifts, it is the smaller donations, sometimes known as “numeral gifts” (someone in the Class of 1992 giving $92, for example) that add up. AG donations are also unrestricted — unlike much of the endowment, which is earmarked for specific programs — and can be channeled wherever the trustees believe the need is greatest. In that sense, notes longtime volunteer Deb Yu ’98, “Annual Giving participation is a vote of confidence in the University, almost an approval rating.”

“If you look at Harvard’s undergraduate participation, it’s garbage! Yale’s is the same. I’ve always relished the fact that Princeton put up such high numbers. It’s like, yeah, we do love our school more than you do.”

— Peter Ryan ’07

Those alumni who give do so for many reasons. Many want to support programs such as financial aid, usually one of the biggest recipients of Annual Giving dollars. Others give out of a sense of gratitude or responsibility. “Everyone who has gone to Princeton has received a tremendous benefit, whether they were on scholarship or not,” insists Tina Ravitz ’76 . “If you’ve ever put ‘Princeton University’ on your résumé, you need to give something.”

Don’t underestimate pride as a motivator, too. “If you look at Harvard’s undergraduate participation, it’s garbage!” Peter Ryan scoffs. “Yale’s is the same. I’ve always relished the fact that Princeton put up such high numbers. It’s like, yeah, we do love our school more than you do.” Ryan has the numbers to back him up. In 2020, U.S. News & World Report published a list of “10 Colleges Where the Most Alumni Donate” and Princeton came out on top, with a two-year giving average of 55%. Dartmouth was the only other Ivy League school on the list, at 44%. (Relatively few universities publish their participation rates, usually preferring to emphasize the dollars raised.)

Whatever their reasons, fewer Princetonians seem committed to giving than a decade ago. The trend, if it continues, could signal some weakening of that rabid alumni spirit for which the University has long been famous. So, this year, entering the final, frenzied month of June, the Annual Giving leadership has set an overall participation goal of 50%, with an ambitious 55% average participation rate for the four youngest classes.

But, as Eisgruber notes, Princeton is battling headwinds, many of them national, societal, and generational. The recent decline in participation may prove to be a hangover from the disruptions of COVID and the unrest that has gripped the campus and the nation over the past decade. It could be a response to the massive growth of the endowment, which has nearly doubled in value in the past decade. Or it might just be cyclical, a passing phase.

But with so much at stake, that would seem like a risky bet to make.

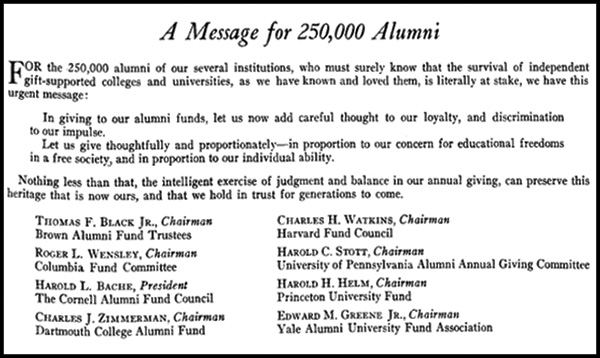

Princeton spotted Yale a 50-year head start in annual giving but moved up quickly. The Elis invented the collegiate annual giving campaign in 1890, followed by Cornell in 1908, Dartmouth in 1915, and Harvard in 1925. Princeton didn’t inaugurate its own effort until 1940.

At a time when the endowment was miniscule, the Princeton University Fund, as it was called, helped balance the budget, but from the outset, participation was emphasized as much as dollars. Annual Giving, President Harold Dodds *1914 declared in that first year, provided “an opportunity for all Princeton men, no matter what their financial position at the moment, to join in an expression of loyalty when it is needed most. Believe me ... it isn’t the size of the gift that is so important. It is the fact that a gift is made.”

Nevertheless, it took time to build a culture of giving. That inaugural campaign remains the weakest in Princeton history, with just 18% participation, the gifts ranging in size from 10 cents to $1,000, as well as two tickets to the Yale football game for resale. The participation rate had nearly tripled by the time individual class campaigns began shortly after World War II.

Though the campaigns were broadened to include parents (1948-49), corporate matching gifts (1954-55), and graduate alumni (1957-58), gifts by undergraduate alums have always been the largest component of Annual Giving. Undergraduate participation topped 70% for six straight years in the late 1950s and early ’60s, setting a record of 72% in 1958-59. Since its inception, Annual Giving has raised more than $1.6 billion from all sources, and nearly 90% of undergraduate alumni have given at least once. Edward Simsarian ’45, the current record holder, has contributed to Annual Giving for 76 years.

All this helps explain the envy that Tom Ryan and other development directors feel. Almost everywhere else, things are different. According to a 2018 report by Hanover Research, only about 18% of alumni of private colleges and universities donate to their alma maters, and only 5% of alumni of public universities do.

However, the report also found that, while the total dollar amount of private donations is going up, those dollars are coming from fewer donors. “Alumni fundraising participation and institutional donor acquisition rates are dropping,” Hanover says, “and institutions increasingly rely on mega-donors to hit fundraising goals.” A 2019 report by the American Council on Education detected a similar trend. “Beyond large gifts, philanthropy to higher education has benefitted from gifts of all sizes and from donors of all income levels,” it said. “However, beginning around the time of the Great Recession, participation rates have declined considerably in recent years.”

This trend can be seen elsewhere. To pick just a few examples, Bowdoin’s overall participation rate fell from 52% in 2019 to 43% in 2022. Holy Cross’ fell from 50% to 39%. And in a 2020 report, Yale’s five youngest classes all had less than 14% participation, and none of its youngest 25 classes was above 25%.

Before considering the reasons for the decline in participation, it is important to keep a few points in mind. First, the recent dip notwithstanding, Princeton still fares far better than nearly anyone else. Second, undergraduate enrollment is growing, which means that in the future it will require more donors to get 60% participation from, say, the 1,500-member Class of 2026 than it did from the much smaller classes of earlier generations.

That said, four factors seem to be driving the current downturn:

1. COVID. In March 2020, with minimal warning, the University sent students home and cancelled Reunions. The Annual Giving office also curtailed outreach efforts during the critical final months of the campaign and, not surprisingly, giving suffered. While the total dollar amount raised slipped by $2.3 million (but was still the fourth-highest total), alumni participation slumped by seven-and-a-half points to 48%, the largest single-year drop ever. Last year, even with the economy recovering and the campus reopened, participation was just 47%.

The youngest classes, which had seen their time on campus cut short, were the most affected. Only 21% of members of the Class of 2021 participated in their first Annual Giving campaign, and 26% of the Class of 2020. (Because of COVID, neither class made a four-year Annual Giving pledge during Senior Checkout, a practice that has now resumed.) “A lot of people didn’t want to give until we had a graduation ceremony,” explains class agent Taylor Jean-Jacques ’20, who thinks that her class will improve its numbers this year. But older classes were affected, too. “COVID really did a number on us,” says class agent Natalie Fahlberg ’18. Brittany Sanders Robb ’13 noted that her class saw a sharp decline in the number of “perfects” — members who had given every year.

2. Politics. This is a contentious time, and the University has been criticized from both ends of the political spectrum. Social media and the internet enable alumni to stay informed about campus issues and then to amplify their opinions in ways that previous generations could not. Disgruntled alums may decide to close their wallets, at least for a while.

An indeterminate number of alumni are doing just that. In 2019, a group called Divest Princeton published an open letter to Eisgruber denouncing the University’s policy of investing endowment funds in fossil fuel companies and pledging to withhold their donations until it stopped. “Until then, we cannot in good conscience give to Princeton,” the letter stated. As of the end of April, the letter had been signed by 3,192 undergraduates, alumni, faculty, staff, and parents.

One of the signers is Amy Dru Stanley ’78, a law and history professor at the University of Chicago. Contacted by PAW, Stanley explained in an email, “It seems more worthwhile to direct giving to institutions that seek to ensure the survival of the planet and its peoples.” Stanley wrote that she has indeed stopped contributing to Annual Giving but she might reconsider since the University announced in the fall that it is divesting from all fossil-fuel companies and dissociating from 90 fossil-fuel companies that participate in the industry’s “most polluting segments.”

Some conservative alumni, disenchanted with current University policies, have redirected their giving from the annual fund to the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions, although the program does not encourage such protest donations. “[W]e are grateful for every gift to the Madison Program, especially those from alumni,” wrote executive director Bradford Wilson, “but we are also grateful to alumni and others for supporting the University as a whole. All units, including the Madison Program, benefit from that.”

To guess at what long-term effects such protests could have, it might be instructive to look to the late ’60s and early ’70s, when the campus was rocked by protests over the Vietnam War and the decision to admit women. Over a two-year period from ’68 to ’70, Annual Giving participation dropped by 10 percentage points, and many knew why. In the May 19, 1970, issue of PAW, featuring a cover story about protests over the U.S. invasion of Cambodia, Winthrop Short ’41, the campaign chair that year, attributed the decline in giving to “a lack of agreement among alumni ... of the changes, both substantial and rapid, occurring at the university.” Alumni attitudes, Short said, “ranged from questioning concern to actual withholding of financial support.” It took nearly 30 years for participation to cross the 60% threshold again, and it has never matched the 66% participation rate of 1967-68. But after a one-year dip, the total amount raised resumed its upward climb.

Whatever their politics, Chris Olofson ’92, who chairs the Annual Giving Committee, urges alumni not to be “one-issue voters” when it comes to Princeton. “I hope that no one issue, including a very important issue, eclipses our long-term relationship with the University,” he says. “I hope that Annual Giving support is not a political tool to endorse or seek a particular policy outcome at Princeton. It is still very important for all of us to stand together to support current students.”

“Naturally, we experience the ebbs and flows of philanthropy generally like everybody else, but we also have the support of our alumni like almost nobody else. I feel optimistic about the future for Annual Giving at Princeton.”

— Chris Olofson ’92, Annual Giving committee chair

3. The endowment. Another factor that may explain the declining alumni participation rate, ironically, is success. Seeing an endowment of nearly $36 billion, many alums, especially in the younger classes, have decided that their giving would better be directed elsewhere. Hanover Research recognized this as well, writing in its 2018 report, “Millennials currently prefer to donate to causes they see as more local and immediate than their alma mater.”

Professor Peter Singer, a bioethicist in the University Center for Human Values, supports this attitude — to a point. “If [alumni] want to do something because they feel that Princeton has been good to them, great, make a modest donation,” he advises. “But in terms of the most effective giving that will do the most good, giving to a university with an endowment that is already [huge], I don’t think that is the most effective thing you can do.”

Writer Malcolm Gladwell made a more provocative suggestion last fall, calling Princeton’s endowment “the world’s first perpetual motion machine” and arguing that the University has so much money it could dispense with tuition altogether and live off the returns. His proposal — perhaps tongue-in-cheek, perhaps not — nevertheless landed like the sound of fingernails on a blackboard in Nassau Hall. Gladwell “assumes a static university,” Eisgruber told PAW, “and a static university is not a living and thriving university.”

A number of alums, however, have decided that Princeton has enough money, though it is hard to identify them and harder to get them to speak on the record. One recent graduate, who has been actively involved in class and University affairs but asked to have his name withheld, says, “Even if I gave $100, what is that going to do?”

Millennials are not the only ones who feel this way. John Rogers ’83, a professor at UCLA, explained to PAW in an email that his reason for not participating “is simply that we focus our giving on groups and institutions who have less resources and who work on issues of economic, health, racial, or educational justice. Certainly, Princeton does work in these domains, and I admire and draw from many Princeton faculty who produce scholarship in these areas. But my view is that the marginal benefit of my modest donations is far greater in smaller organizations with a more targeted focus.”

Class agents say they combat the “Princeton doesn’t need my $100” argument by emphasizing how Annual Giving makes it possible for Princeton to attract a more diverse student body, enabling those from families of lesser means to attend tuition-free. But another important response, made by Eisgruber and others, is that giving is not an either/or proposition. Says Olofson, “All of our alumni have a range of interests and we do not ask them to support the University to the exclusion of other great causes, but to instead include Princeton in their giving interests each year.”

Ravitz puts it more bluntly, saying, “Yes, your $50 might be more needed by a local food bank, but you can still participate and put $5 in the Princeton kitty.”

4. Overload. A final factor is simply overload. It seems that nearly everyone these days has a professional fundraising operation, from political candidates and private schools to arts groups and local businesses. Alums are bombarded with requests for money nearly every day, making it hard for Princeton to stand out. Peter Ryan describes a solicitation arms race over the 16 years since he graduated. “No one picks up their phone anymore, so we switched to blast emails, but no one reads those, so we switched to texts, and people opt out. The speed of technology has just eroded those channels. We have to keep reinventing the wheel every five years and it’s exhausting.”

Annual Giving officers say they are aware of the issue and are trying innovative ways to address it, paying particular attention to recent graduates. Last November, for the first time post-COVID, volunteers from the 10 youngest classes returned to campus for a day of AG training. Young alumni have been added to the national Annual Giving Committee, and a new mentoring program pairs members of recent classes with more experienced AG volunteers. In March, the monthlong Forward Together Challenge matched the first $50 given from donors in all classes, targeting those small donations that drive participation.

The most successful class agents try a variety of approaches to break through the background noise, soliciting classmates through an “all of the above” approach of mass mailings, personalized letters, blast emails, targeted follow-ups, phone-a-thons, individual phone calls, and texts. Some also send each donor a handwritten thank-you note.

“Different people prefer different methods,” says Vasanta Pundarika ’06. “You just don’t know.”

Yu, an AG volunteer since 2006 who now runs the mentoring program, boils her advice down to three points. First, make the request as personal as possible, knowing each potential donor’s interests and connection to Princeton. Second, don’t be pushy, but instead ask people to consider giving. And finally, listen to people’s concerns.

Persistence also pays off. The Class of ’73, which is celebrating its 50th reunion this year, has set a goal of 50% participation. Class agent Jan Hill ’73 has tried everything. In her outreach, she plays on shared memories, class pride, and even current events. On International Women’s Day, she emphasized that to classmates who were among the first class of women to graduate from Princeton. When Princeton’s basketball teams went to March Madness a few weeks later, Hill emphasized that.

“There’s no such thing as too many ‘asks,’” Hill believes. Keep trying. Sometimes she stops beating around the bush altogether, sending emails with a message line that reads simply: “Come on, donate. It’s your 50th.”

At the kickoff of the 1953-54 campaign, an unsigned essay in PAW made the case for why the University, even with a $63 million endowment, still needed alumni support. “To the anticipated [question], ‘Will Princeton’s need for money never cease?’ the directors of the Fund are prepared to answer boldly: No, not as long as Princeton has unfulfilled opportunities, not as long as Princeton can show economy and efficiency in operation, not as long as there is an alumnus who is failing to give what he can on a scale commensurate with his affection for Princeton.” That campaign garnered nearly 68% participation.

Seventy years later, the finances may have changed, but the message has not. “I do hope that people will think in particular about participation and the special benefits it has in terms of the intensity of feeling of our alumni community,” Eisgruber says. Olofson expresses confidence that AG participation will climb again. “Naturally, we experience the ebbs and flows of philanthropy generally like everybody else,” he says, “but we also have the support of our alumni like almost nobody else. I feel optimistic about the future for Annual Giving at Princeton.”

With four weeks to go, phones are ringing, texts are pinging, and emails are going out in pursuit of this year’s goal of $70 million and 50% participation. And up on Cape Cod, Peter and Tom Ryan will again await the outcome, with breakfast on the line. How will the family bet go this year?

“Peter will do all right,” Tom predicts, “but I’m gonna push him.”

***

In early July, the University announced that this year's annual giving campaign raised $73.8 million on the strength of 47.5% participation by undergraduate alumni, up one-tenth of a point from last year. Up in New England, though, the annual bet between Peter Ryan '07 and his father Tom, Holy Cross Class of 1976, went into overtime.

Contacted by PAW, Peter Ryan wrote in an email, "I was on the phone with my dad yesterday and started the conversation with, 'Does your number (%) start with a 6...?' and he said, "Well... yes.' Knowing that [the Class of 2007] finished at 60.1%, I was all but ready to concede defeat. Turns out [his class] is sitting at 60.0% BUT has a final gift that's had an issue processing, which will take them to 60.4%. So, sadly it looks like I'll be ponying up for breakfast on the Cape, but happily so. "

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

18%

1940-41

Princeton’s participation rate for its first Annual Giving campaign.

52%

1950-51

A decade later, the participation rate jumps with more than half of the alumni giving.

72%

1958-59

Participation reaches a new high, which has never been matched.

$3 million

1967-68

After starting at $80,000 in 1940-41, giving exceeds $3 million for the first time. Adjusted for inflation, this is the equivalent of $26 million in 2023.

56%

1969-70

Participation drops from 66% in 1967-68 amid the Vietnam War and the start of coeducation.

$17.5 million

1986-87

Giving hits a new high for the 12th year in a row. This total is equal to $46.5 million in 2023.

$44.6 million

2008-09

Giving declines by nearly $10 million from the previous year as the Great Recession hits.

47%

2021-22

Participation is at its lowest since 45% in 1949-50.

$81.8 million

2021-22

Giving is at its highest, surpassing the $74.9 million raised in 2016-17.

15 Responses

Chris Reeve ’72

2 Years AgoAthletics Giving and Annual Giving

Further to your June 2023 article “The Giving Plea,” whilst you mention competition as a cause for reduced participation, you should note that Princeton itself creates such competition and erodes the gift pool through its Tiger Athletics Give Day (TAGD). I was not aware my TAGD gift would not count towards Annual Giving until Reunions, almost too late. Why not include the TAGD gifts and donors in AG? Whilst TAGD can be targeted, it’s all going to support Princeton, and will reflect well on our giving records, and encourage giving to TAGD as well.

Dan Armstrong ’72

2 Years AgoImpact of Divest Princeton

Mark Bernstein’s piece in the June PAW, “The Giving Plea,” reports a record $81.8 million in giving last year (2021-22) despite the percentage of gift-givers, which has often surpassed 60%, falling below 50% for the third year in a row. Bernstein offers four reasons for this, one being politics. He mentions Divest Princeton. Its open letter asks signers to stop giving until Princeton divests completely from fossil fuels.

Of roughly 97,000 alumni, less than 800 graduating before 2017 have signed the letter. To no surprise, however, graduates since then are signing at a rate many times greater than their elders. They are more actively concerned about climate change because they are young and the consequences are their future. To them, climate change is real, is directly related to fossil fuels, and, as we can all see, has infuriated Mother Nature. Even if you don’t believe the fossil fuel part, be sure that Princeton University as an academic institution does — why else would it be investing billions of dollars in a net-zero carbon campus and so many hours of research into climate change?

If new graduates continue to sign the letter at their current rate, Princeton stands to gain more financially by divesting from fossil fuels than not because of the increased giving it would bring. Princeton’s net-zero carbon campus will be one of a kind, a shining light to the world. Wouldn’t it be silly if we’re still putting the Tiger in the proverbial tank when it’s completed?

Liz Hallock ’02

2 Years AgoHow Alumni View Their Degrees

I’m genuinely curious if alumni giving has studied how Princeton grads are doing when it comes to admission to prestigious grad schools. Gone are the days when all the prestigious law schools are recruiting from the Ivies. I just met up with a former employee of mine who earned his undergraduate degree online while working at Starbucks and now is studying at Yale Law School, a school I never would have dreamed of attending as I was not in the top 10% of my Princeton class.

As more American students attend college, having a college degree has become devalued. And where one goes to graduate school has become more important. I am wondering if newly minted Princeton students are finding that their undergraduate degree is not opening the graduate doors that they would like, as that same degree did for classes of the past?

Personally, I agree with Peter Singer’s utilitarian approach and I send my money to organizations with more need: my local school district’s school lunch program, the local animal shelter, and I send as much as I can afford to Eastern Washington Planned Parenthood.

William P. Wreden Jr. ’62

2 Years AgoCommitment to Giving

In President Eisgruber’s interview in PAW’s May issue he described being a Princeton graduate as a “lifetime bond” or commitment. When I matriculated at Princeton and, prior to that at my prep school, I didn’t register that I was making lifetime commitments, but I have honored them in gratitude for the education I received.

In PAW’s June issue I read with interest Mark Bernstein’s article, “The Giving Plea,” as one who has annually paid class dues and contributed to the class scholarship fund, to Annual Giving, albeit usually modestly, and to the Princeton University Rowing Association through the Princeton Varsity Club. I joined the 1746 Society with a provision in my will to donate a portion of my estate to Princeton if funds remain after health care and end of life expenses have been paid.

I appreciate that for political reasons some graduates may decline to contribute — I have read that even a Supreme Court justice has minimized his connection to Princeton — and a classmate at our 50th reunion said, given the size of Princeton’s endowment, that he declined to give.

Like many of us, I am overwhelmed almost daily with envelopes arriving in the mail requesting donations for worthy causes. We each have to decide what is important to us. I do what I can with Princeton and my prep school at the top of my list. Since Putin’s brutal and criminal invasion of Ukraine I have contributed extensively to organizations aiding Ukraine.

Massie Ritsch ’98

2 Years AgoPrinceton’s Resources and Alternatives to Alumni Giving

Responding to “The Giving Plea” (June 2023), I had a window into alumni fundraising this past year as an Annual Giving volunteer for 1998’s 25th reunion campaign. The University’s fundraising professionals helpfully armed us solicitors with fact sheets, messaging, outreach tips and memes to counter the forces that have deflated alumni participation in Annual Giving by 21 percent since our class graduated. Princeton’s campaign that just concluded failed again to inspire more than half of all alumni; only 47.5 percent of undergrad alums contributed.

Post-campaign, the fundraisers’ talking point that echoes with me acknowledges that a university with a $36 billion endowment can succeed without its graduates’ money: “Princeton is not needy,” we volunteers were encouraged to tell our reluctant classmates, “but it is worthy.”

“Worthy” implies two things here: 1) The University will use donors’ money to advance noble interests, and 2) while doing so, it will spend money efficiently. On Princeton’s first assertion, I have no doubt. The University’s impact is clear as a world-class research institution that is expanding college access and turning out graduates who serve humanity. The second assertion, however, merits interrogation.

If Princeton’s endowment at its last public tally were carved up among every undergrad and graduate student, each would be individually backed by more than $4 million. The University commits to spending 5% of the endowment’s value every year. That’s equivalent to $200,000 for each student on campus — without even one dollar from tuition, fundraising, or research grants.

Shouldn’t $200,000 annually cover a Princeton education?

Pooled together, $200,000 per student, per year, should be enough to pay professors $400,000 in salary and benefits and give each a teaching load of only four students — and a 300 square foot office to meet with them. There would still be ample funds for uniquely generous benefits for every student as well, including year-round rent on a one-bedroom apartment in the Princeton area, with utilities paid, a generous per diem for meals, books, technology, a $100 daily “resort fee” to cover campus activities and facilities, flights to and from home, health insurance, and a $500 per week summer stipend. And there would still be $11,000 a year, per student, to fund research labs, administration, and other costs. You can see this breakdown for yourself at bit.ly/AnnualGivingForward — along with my idea for an alternative to alumni giving that would “spread the wealth” to needy and worthy causes aligned with Princeton’s mission.

With all its wealth, could Princeton be the first top-tier university to go tuition-free? Seems like it could. Should it? That’s debatable. However, what is clear is that the University can continue to thrive without asking its alumni for money.

Steve Alfred ’56

2 Years AgoMacro Factors in Giving and Participation

I read with great interest "The Giving Plea" article by Mark Bernstein ’83 in the June issue. As a long-time class agent for Annual Giving, I have been curious as to the phenomenon of rising dollar contributions and declining percentages of participants. The article does a fine job of discussing the history of Annual Giving and potential factors that might be contributing to that decline in participation at Princeton.

But as President Eisgruber is quoted as saying in the article, this is not a Princeton-specific phenomenon. That is both a positive and negative factor. It suggests that Princeton is not doing anything inappropriate, but it also indicates that it could be a significant challenge to fix it.

What are the factors external to Princeton that might be contributing to this result? Well, one of them to my mind is the growing disparity in income and wealth, as so eloquently expressed by Thomas Piketty in his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century. He noted the trend for fewer members of society to earn considerably greater income and garner much greater wealth, while much of the rest of the population falls behind. In the charitable sector, this can easily lead to larger gifts by fewer donors along with a decline in donors who feel they are not “keeping up” economically.

Like so many things, there are usually multiple causes, not just a single one.

Allison M. McKenney ’75

2 Years AgoQuestioning the Maximization of Wealth

I read with interest the article “The Giving Plea.” I am one of those alumni who do not donate to Princeton. It is partly due to reason number 3: the endowment. Princeton has a $36 billion endowment, and they’re still begging for more? Like nearly all major institutions (profit or nonprofit), the word “enough” does not seem to be in their vocabulary.

However, there’s another reason: I’m reminded of Thoreau’s writing of those who “serve the state chiefly with their heads; and, as they rarely make any moral distinctions, they are as likely to serve the devil, without intending it, as God.” This pretty much describes what Princeton is about, both in how it educates and in the behavior of its administration and many of its graduates. Princeton and the economic and political systems it serves are ultimately about the maximization of wealth and power in the hands of individuals and institutions, and this amorality is one big reason why our society is unable to effectively deal with the enormous problems that threaten our civilization and even our survival.

Laurence Clark Day ’55

2 Years AgoSupporting Princeton With Dues of One’s Choice

Princeton’s approach to annual giving misses the mark. Why? It stresses one’s intellectual attitude when it should focus on our emotional response. Low key the chants “going back” and “giving back.” We never left!

Princeton is not a society, an organization, an association, a nonprofit, or a business in any general sense. Decades earlier male only, applicants who applied for admission were well aware Princeton in name and reputation was more than a highly selective academy with academics as its core role. Princeton’s aura encompassed global leaders in past centuries and the present in every field of endeavor, whose names a few we could recite.

We alumni in earlier decades subliminally felt we were invited to be eventual equal members of a highly exclusive set of individuals of great esteem who were now aligned in a bond for life.

As Princeton reached far out to bring to the fold females and others who saw our university in the narrow focus as an academic institution only, the leading University lights should address new incoming students in a presidential speech that “Princeton” is for you now to be a co-equal and integrated member of a selective exclusive group that encompasses a wider ideal beyond the purely four years of specific academic coursework.

All alumni are exclusive lifelong bonded members of a name that is viewed and reflected upon as a “club.”

We are members of a club. We visit our club headquarters at any time for any reason to meet with other members for meals and conversation.

As lifetime members of our club called Princeton, we are encouraged to deposit annual dues, a sum of one’s choice.

Dues delivered periodically are the emotional expression outward to reaffirm being one in a unique, highly exclusive body of which we are all proud beyond description.

We do not “go back” to our club. We have never left!

Christopher Greene ’81

2 Years AgoA Simple Way to Honor Loyal Giving

“The Giving Plea” (June issue) raises an interesting question. Princeton says that it values a high participation rate in its annual fundraising, but does it practice what it preaches? If Princeton truly valued participation, wouldn’t there be a prominent program that recognizes it?

One of my other alma maters, Stanford, has such a program but unfortunately it is weak. Still, the idea is in the right spirit and it has a great name — Stanford Loyal. Regardless of gift size, anyone who makes a gift to the Stanford Fund for three or more consecutive years is deemed Stanford Loyal. What makes this weak is that there is no distinction between someone who has given three years and someone who has given 10, 20, 30, or more years. Also, if a year is skipped that person is no longer Stanford Loyal even if they have given every year but one since graduation. With this program design, one either is or is not Stanford Loyal, a status easily attained but also easily lost. Maybe Stanford’s IT heritage causes it to prefer binary systems.

But Stanford is on to a good idea, one Princeton could take to a much more effective level. Princeton has excellent alumni giving records so it could implement such a program quickly for all existing alumni classes as well as moving forward. Lapel pins for achieving consecutive 5-year Annual Giving participation milestones are something that many alumni would choose to add to their beer jacket or class blazer, not only showing pride but promoting the concept of that everyone should give every year. This also could be introduced to current students who want to get a jump on matters. Someone could be sporting a 5-year pin at their first reunion!

Large donations are important and recognizing gifts by size is appropriate. But if Princeton truly also values participation rates, a second program to recognize that loyalty would encourage and reward true “annual giving.” This also is a more democratic form of recognition that helps build community, something Princeton classes are rightly proud of having but that needs nurturing.

A program recognizing the number of Annual Giving campaigns by 5-year milestones would acknowledge loyalty regardless of a person’s financial means. Then Princeton would practice what it preaches when it comes to participation rates.

Terry Vance ’77

2 Years AgoA Reason Not To Give

I was surprised to read in the article on the endowment that alumni were reluctant to go on record as to why they have ceased to give. I am very happy to go on record.

I chaired the Class of 1977’s 25th reunion major gifts campaign. I was proudest of Princeton years ago when it challenged alumni to grow the endowment to enable loans-free admissions. The nadir came during COVID, when Princeton effectively charged full tuition despite closing the campus. I had thought one use of the endowment would be for emergencies exactly like this one. But no, I am informed the endowment must always grow, not only from the investment returns on its huge base, but also through additional alumni donations. Is it reasonable to believe that if President Eisgruber ’83 finds something new that he would like to build, that the largest endowment per student in the country (by far) may not be sufficient to fund it?

I don’t think Malcolm Gladwell had his tongue in his cheek when he wrote about the Princeton endowment — I think it was pointed straight at Nassau Hall.

I believe that future appeals for alumni support will need to be factually and rationally based, rather than tugging on emotional bonds and creating a false competition with past results.

Richard M. Waugaman ’70

2 Years AgoRobert Putnam Has an Answer

Good article, with several cogent explanations for the decline of alumni participating in annual giving since those six straight years of highest participation in the late ’50s and early ’60s.

In Robert Putnam’s terrific 2020 book The Upswing: How America Came Together and How We Can Do It Again, he describes those very years as when the U.S. was the most cohesive during the past century, on multiple measures. Even the use of “we” compared with “I” peaked then, according to Google Ngram. Americans were much less divided by political ideology. In Putnam’s vivid image, we’ve become solitary cowboys rather than a wagon train of interdependent pioneers (yes, their exploitation of Native Americans spoils that image).

Americans have also become less active in religious communities. Those who attend religious services regularly give more than do others to non-religious charities such as their alma maters; are more than twice as likely to volunteer for non-religious organizations and to be active in civic life.

Studies have shown that wealth is inversely correlated with empathy, which helps explain why the entitled wealthy often rationalize wanting to lower (or evade) their taxes at the expense of those in dire need. Research even shows that drivers of luxury cars are far less likely to stop for pedestrians in crosswalks than are drivers of the cheapest cars.

I’m more and more grateful to Princeton as I age. Most of my wife’s and my charitable giving is to organizations that serve the poor. One of the many reasons I donate to annual giving is to support what Princeton has increasingly done for students from families of limited means. Such programs are vital to live up to our national ideal of equal opportunity for all.

Larry Leighton ’56

2 Years AgoReinforcing Reasons to Give

As one of Princeton’s major strengths has been its sense of family and cohesion, the steady decline in participation rates is a very negative symbol of what may be happening with our undergraduate demographic (admissions, please note).

As a freshman way back in 1952 I recall, as a part of freshman orientation, being told that we were all benefitting from gifts from alumni who preceded us. Accordingly, we were expected to contribute to benefit the Princetonians who would follow us.

It is likely that current and recent graduates are endowed with two unhelpful traits.

First, they may have the sense of entitlement. Princeton should be blessed to have me and not expect me to contribute.

Second, there seems to be very little knowledge of the importance of philanthropy generally. For whatever reason, neither family nor any institution has educated these people about the importance and gratification of giving to a very important institution.

It is clearly too late after students graduate to start preaching Annual Giving.

My strong suggestion is that as a compulsory part of freshman orientation the University have a seminar that teaches the overall importance of philanthropy in one’s life. It should then emphasize that these students are benefitting from gifts from those who preceded them and that they should help those who will follow them.

Princeton’s large endowment didn’t fall from the sky but from alumni giving, so those who are benefiting from it should learn who it came from.

In my own case, I have given to Princeton every year since I graduated in 1956. It just seemed to be the right thing to do. It is also a pleasure to contribute to a “winning team.”

Jethro Miller ’92 s’93 p’27

2 Years AgoRoom for Improvement in Fundraising Practices

As a longtime Annual Giving volunteer, I am very concerned by the downward trend in participation rates. As a professional fundraiser who deals with concerns similar to those highlighted in the article (“The Giving Plea”) on a daily basis, I would encourage the University to lean in to the proven practices that are being employed by other nonprofit organizations and to question some of the traditions that have been central to the Annual Giving program over the years.

By encouraging alums to create set-it-and-forget-it monthly giving rather than focusing on one-time gifts, the University could forego annual solicitation for a portion of each class. Many organizations make monthly giving the initial request for all donors.

While the focus on peer solicitation is the hallmark of the Princeton approach, has the investment in staff and technology kept up with the growth of the alumni base and the total dollars raised? A ratio of 25 staff to $81 million for a program focused on participation is very low. And other organizations are actively using AI-informed technologies to identify who, how, and when to solicit.

One of the tenets of the Annual Giving program has been to minimize its focus during Reunions. But why? By not actively soliciting when huge numbers of alums are gathered in one place, the major classes miss out on a great opportunity.

I’d also ask if, in determining participation rates, the differentiation between Annual Giving and restricted giving (e.g., for capital or sports teams) still serves a valid purpose given the size of the institution’s overall budget, or if it just discourages alumni engagement and giving.

It’s time to ask serious questions about Annual Giving if the University hopes to return to the participation rates of the past.

Lindianne Sarno Sappington ’76

2 Years AgoWhy I Ceased Giving to Princeton

I ceased giving to Princeton University because of what the University administration did to Professor Joshua Katz in an egregious violation of his right to free speech. My decision was constitutional, not political, and in keeping with the teachings of the late Professor Walter F. Murphy. I now send a monthly donation to Hillsdale College because Hillsdale teaches and abides by the Constitution. I urge the University to apologize to and reinstate Professor Katz.

James Andersen ’84

2 Years AgoReasons for the Rapid Decline in Participation

I have a similar but slightly different take on the reasons for a rapid decline in participation. There is no doubt the size and incredible growth rate of the endowment is a major factor. There is no logical way for Princeton to say it needs anyone’s donation. The average gain on the endowment has been 10% per year for 20 years so expected annual earnings of $3.6 billion are more than the entire annual budget of about $2.9 billion. By any standard I am wealthy but if I gave my entire net worth to the University it would have absolutely no impact on the school or anyone’s outcomes.

I wouldn’t use the word “politics” to describe the disillusionment of alumni but rather the fact that Princeton has strayed far from its mission of truth-seeking and its once strongly held beliefs in free speech, civil discourse, and the exchange of ideas, even unpopular ones. Many students and faculty members self-censor and there is an overwhelming leftward tilt at the school that interferes with the pursuit of knowledge (wherever that pursuit might lead). Why should alumni support a school that no longer lives the mission we experienced as undergrads?

Finally, only a fool would contribute to an organization as inefficient as Princeton. While the University doesn’t publish per student expenditure data, adjusting for sponsored research and the PPPL, total expenditures suggest the University spends more than $250,000 per enrolled student annually. Where does all the money go? It’s an absurd waste of resources.

I’m grateful for all I received at Princeton but I don’t feel the need to continue to support financially a school that no longer believes in the values I do and that wastes so much money (which it doesn’t need) when I can make multiple contributions to other organizations that will have 100 times the positive impact any dollar I send to Princeton will.