Glenn Dryfoos ’83 Just Released Jazz Great Benny Carter’s Princeton Recordings

‘Benny … is the Joyce Carol Oates, the Arthur Lewis, the John Nash of jazz,’ Dryfoos says

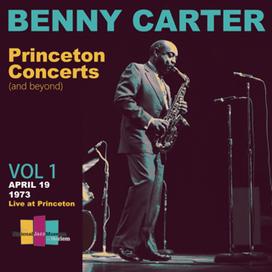

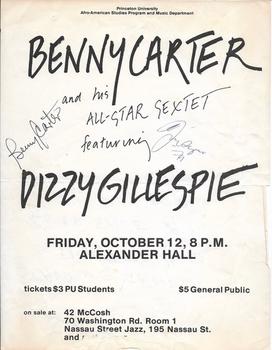

In the fall of his freshman year, Glenn Dryfoos ’83 paid $3, filed into Alexander Hall, and watched one of the greatest alto saxophonists of all time perform: Benny Carter, then 72.

“I was kind of expecting him to sound like an old guy,” says Dryfoos, a jazz enthusiast who in high school had seen Benny Goodman, Lionel Hampton, and some of Carter’s other contemporaries perform live. Those musicians, while great, had sounded like “time capsules” to his ears; Carter was a different story. “It was just a damn good jazz concert. It was vibrant. It was alive. It was modern.”

Between 1973 and 1997, Carter performed eight times in Alexander Hall, usually accompanied by other renowned jazz artists, including Dizzy Gillespie, Clark Terry, and Hank Jones. At the invitation of Professor Morrow Berger, Carter also taught classes in the sociology and American studies departments. Berger’s sons — Ken, Larry, and Ed — recorded the Princeton concerts with Carter’s blessing, but for decades, the records collected dust.

“As far as anybody knows, these are the last unreleased recordings of Benny Carter,” says Dryfoos. “They will also be perhaps the last unreleased recordings of Dizzy Gillespie, Clark Terry, Hank Jones, Barry Harris, and many, many other legendary jazz musicians who joined Benny for these Princeton concerts.”

Aside from being one of the two great alto saxophonists of pre-bop jazz, Carter was also an accomplished composer and arranger. Tony Bennett, Frank Sinatra, and Ray Charles all performed music he wrote, and he scouted Ella Fitzgerald and gave an early break to a young Miles Davis. In a genre known for its fast-living, fast-dying artists, Carter stood out for his longevity.

“Jazz musicians just didn’t live to 70, never mind be fantastic at that age,” says Dryfoos. “Never mind live to 90 and be fantastic.” In a tribute to Carter after his death, Dryfoos wrote:

“He was renowned on two continents at a time that Ruth and Gehrig were playing for the Yankees, and still … at the top of his craft when New York was winning championships with Derek Jeter and Bernie Williams.”

Carter was also a civil rights leader, playing a key role in integrating the Black and white musicians’ union in Los Angeles in the ’50s. He successfully challenged restrictive housing covenants to buy a home in a white neighborhood, and he was the first Black composer and arranger in Hollywood, writing for TV and movies. According to Quincy Jones, Carter showed producers and studios that they “could go to Blacks for other things outside of blues and barbecue … He was the pioneer, he was the foundation.”

“We do a great job of extolling our Nobel winners and scholars, and we should do that,” says Dryfoos. “But Benny — he is the Joyce Carol Oates, the Arthur Lewis, the John Nash of jazz. And his time at Princeton was incredibly meaningful to him.”

No responses yet