Grappling With History: Symposium on Princeton’s Ties to Slavery Explores Lessons, Context, What’s Next

The Friday before Thanksgiving, Princeton dignitaries cut a symbolic orange ribbon and officially rededicated 181-year-old West College as Morrison Hall.

That same day, a speech by the building’s namesake — retired Princeton humanities professor Toni Morrison, the Nobel Prize-winning author of novels chronicling slavery’s impact on American life — inaugurated the weekend’s other big event: a symposium unveiling the results of more than four years of research into the University’s extensive but little acknowledged pre-Civil War ties to slavery.

The juxtaposition of the two events — a scholarly look at Princeton’s troubled racial history, and the renaming of an administration building after an African American writer — underlined one of the central themes of the research effort, known as the Princeton & Slavery Project: the inextricable entanglement of freedom and bondage, progress and oppression.

“Princeton’s early history exemplifies the central paradox of American history, writ small,” history professor Martha A. Sandweiss, the project’s founder and director, told the audience at the Nov. 17–18 symposium. “From the start, liberty and slavery were intimately entwined.”

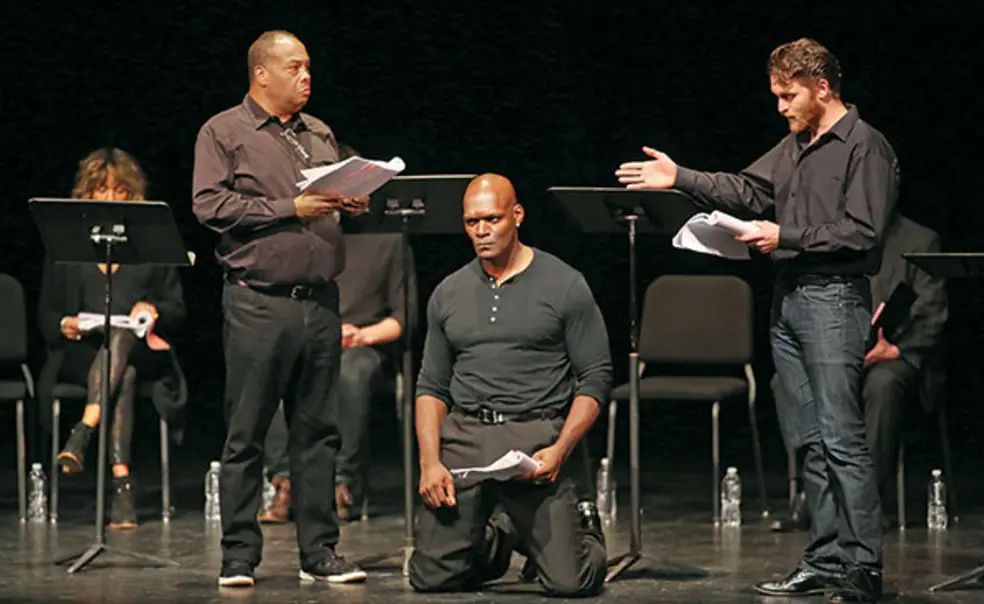

The Princeton & Slavery symposium anchored a weekend that included McCarter Theatre readings of seven short plays based on documents uncovered by project researchers; the premiere of a documentary film by Melvin McCray ’74 about contemporary Princetonians’ family ties to slaves and slaveholders; and an outdoor installation by contemporary artist Titus Kaphar commemorating a slave auction advertised at Maclean House in 1766.

LISTEN ‘It’s Not Just History’: An Atelier Course Explores Princeton’s Slavery Ties in Song

Attended by an audience of several hundred, the symposium featured panel discussions among a dozen researchers, scholars, and academic administrators who presented highlights of the research, placed Princeton’s story in larger historical and contemporary contexts, and began a conversation about how the University should respond to the findings.

Since its Nov. 6 launch, the project’s website, https://slavery.princeton.edu, had been accessed from 95 countries, Sandweiss told the symposium audience. The site includes nearly 90 essays comprising some 800 printed pages, plus more than 370 primary-source documents, videos, maps, and graphs — the result of a collaboration among 40 researchers, from undergraduates to established scholars.

In symposium presentations, five of those researchers summarized their findings on such topics as the life of John Witherspoon, one of nine slaveholding Princeton presidents; the tense, sometimes violent relationship between the University’s Southern students and the town’s vibrant community of free blacks; and the close familial and ideological ties linking University alumni across the South. (For more information on the research, see the Nov. 8 issue of PAW.)

Although the University itself apparently never owned slaves, “slavery and racism became part of the DNA of Princeton,” said Joseph Yannielli, a postdoctoral associate at Yale’s Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition, who worked on the Princeton & Slavery Project as a postdoctoral fellow at Princeton in 2015–17. “The result was a catastrophic failure of moral leadership.”

But Princeton’s entanglement with slavery was not unusual, symposium speakers noted. From China to Rome, “few cultures or nations can be said to have begun or can be said to have survived without slavery,” Morrison said in her keynote address. “Enslaved populations built civilizations.”

In the United States, “slavery was an institution that underpinned capitalism, that made the wealth of the New World possible, that fueled the Industrial Revolution,” said symposium speaker Leslie M. Harris, professor of history at Northwestern University. “The Princeton example reminds us that support for slavery existed dangerously late in the life of our nation as a whole, not simply in the South, but in the North.”

Still, acknowledging the University’s involvement in America’s original sin may change how Princetonians feel about their institution, speakers said. Lesa Redmond ’17 said her research on Witherspoon had helped her, as an African American student, to “redefine my relationship with Princeton.”

History graduate student R. Isabela Morales, project manager of the Princeton & Slavery website, said she walks the campus with a new awareness of the human suffering caused by the men whose names adorn University buildings. “That history’s always been there,” Morales said, “but now it’s visible to us.”

“This is a project that could hurt,” noted researcher Trip Henningson ’16. “We might be shattering some of these mythologies about Princeton that are very important to people, so you have to be gentle, you have to be empathetic. But at the same time, there’s a profound search for truth that I’m really, really proud to be a part of. In order to love a place, you really have to know what it is.”

More than 30 universities have undertaken similar research into their historical ties to slavery, in some cases sparking controversy. Brown University, which launched one of the earliest such efforts in 2003, received negative press coverage and enough hate mail that then-President Ruth J. Simmons stepped up her security detail, Simmons told the symposium audience.

But Princetonians seem proud of the work, President Eisgruber ’83 said. On the day The New York Times covered the project’s findings, Eisgruber was meeting with New York alumni, and “they were jubilant about it,” he told the symposium audience, “because they thought it was a manifestation of the kind of truth-seeking that a university should do.”

Symposium attendees echoed that sentiment. “I think it’s inspiring,” said English professor Esther Schor, acting chair of the Humanities Council. “I’ve been here 30 years, and I feel like I’m completely renegotiating with the institution. I didn’t know any of this.”

Crucially, the project’s website makes emerging scholarship about the place of slavery in American life broadly accessible to people who may never set foot on campus, speakers said — an important way of preserving historical memory.

“We have had this incredible scholarship pouring out for decades, and yet we haven’t quite managed to penetrate our amnesia,” Harvard political theorist Danielle Allen ’93 told the symposium audience. “We haven’t quite answered the question of how we get the summation to stick, so that it’s not the case that one generation after the next has to relearn all of this history.”

Forthrightly accepting uncomfortable historical truths is a precondition for present-day reconciliation, in whatever form it may take, symposium speakers argued. Although some universities have responded to their own slavery studies with concrete gestures of atonement — Georgetown is offering preferential admission status to the descendants of slaves the university sold in 1838, and Brown invested in the local public school system — no specific commitments emerged from Princeton’s symposium. Speakers suggested integrating project findings into campus tours, addressing elements of the history during freshman orientation, and installing 19th-century photographs of Princeton’s African American employees on the walls of University buildings.

“The most important thing for us to do is to continue conversations and events that engage in a serious and truth-seeking and broadly disseminated fashion with difficult questions,” Eisgruber said in a brief interview after the symposium. “Those include questions about history and questions about the past.”

Ultimately, uncovering past injustices must motivate a commitment to eliminating present ones, symposium speakers argued.

“We are making history today, and we forget that,” said Simmons, the former Brown president. “We worry so much about what transpired in the past. We worry little about our complicity in the things that are going on today, and what people will have to uncover about our acts tomorrow.”

For the record

This story has been updated to correct a quotation from R. Isabela Morales.

5 Responses

Ron Naymark ’67

8 Years AgoTime for a New Social Movement

“Grappling With History” (On the Campus, Jan. 10) makes us Princetonians proud that our university has presented us with a challenge to be ever more just and relevant to our time. The article ends with two specific challenges to us: to orient our lives to justice (“Ultimately, uncovering past injustices must motivate a commitment to eliminating present ones ...”) and to actively engage in justice (“We are making history today …”). Recalling slavery reawakens us to a serious injustice in our time. America’s women (over half of our population, as our mothers, wives, daughters, and other important people in our lives) have experienced, or fear, injustices and attacks because of being a woman.

I challenge myself and fellow male Princetonians to be co-agents with our newly vocal “sisters.” We see from history that slaves acting alone could not un-enslave themselves; they required a dedicated abolitionist movement of the enslavers, namely whites. Women now require a dedicated abolitionist-like movement of men who are dedicated to standing shoulder-to-shoulder with activist women, awakening our country to the imperative of no-longer-delayed respectful treatment of women.

Let’s call our effort “Men for Women.” Contact me at ronnaymark@gmail.com, and we can get it started. I have no preconceived agenda or tactics. Let’s figure it out and be a vocal, proud, and important part of a long-overdue, and now rapidly growing, social movement.

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoFocus on a Current Problem

Why are y’all spending so much time on worrying about Princeton and slavery? Everyone was at that time involved with slavery, North and South. Here is a current problem the Princeton community could more profitably spend its time on. Statistics show that the state which incarcerates the largest percentage of its black population is – hold your hats – New Jersey! Wonder why?

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoI truly fail to see what...

I truly fail to see what discussion of slavery and Princeton has to do with anything today. It seems rather an exercise in liberal masochism.

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoAntisemitism has been much...

Antisemitism has been much more destructive, physically, emotionally, morally and historically, than slavery.

stevewolock

8 Years AgoFor the Record

An article on the Princeton & Slavery symposium in the Jan. 10 issue incorrectly quoted history graduate student R. Isabela Morales, project manager of the Princeton & Slavery website. Describing a new awareness of the suffering caused by those whose names adorn University buildings, Morales said: “That history’s always been there, but now it’s visible to us.”