The kitchen can be the most intimidating room in the house after a long day of work, when another night of take-out or microwave food seems a much easier alternative than turning on the stove. But for some alumni, cooking is both a passion and a profession.

PAW senior writer Mark F. Bernstein ’83 spoke to five alumni chefs who took different routes to the kitchen: Some wanted to cook from an early age, while others fell into it more or less by accident. Here, they share their stories and advice.

Valerie Erwin ’79

The right culinary niche and the right location are two of the most important factors in starting a new restaurant. Valerie Erwin ’79 has found both as the owner and chef of the Geechee Girl Rice Café, located in the Mount Airy section of Philadelphia. Geechee Girl takes its name from the West African slaves, known as Geechee or Gullahs, who lived in the coastal areas of South Carolina, Georgia, and northern Florida. The Geechee are believed to have introduced techniques to simplify rice harvesting, and so Geechee Girl Rice Café specializes in what has come to be known as Low Country cuisine, featuring shrimp, chicken, gumbo, grits, and especially rice, which accompanies each dish.

Erwin says she learned to cook when she was 8 years old, taking over when her mother was in the hospital having a baby. At Princeton, where she was a politics major, Erwin worked in the dining halls and does not recall Commons food fondly. “You just went there and ate the food,” she says. “Everybody complained about it, but no one did anything about it.”

She worked for a foodservice company before applying for a job at The Commissary, an “upscale cafeteria” created by legendary chef Steven Poses, who is credited with starting Philadelphia’s restaurant renaissance in the 1970s. Although she did not expect the move to cooking to be permanent, Erwin remained at The Commissary and two other Phila-delphia restaurants for more than eight years, surviving a trial by fire in the quick, precise, high-pressure job of filling diners’ orders as they come in, a position known as cooking “on the line.” Line-cooking, writes chef Anthony Bourdain in his book Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly, requires “blind, near-fanatical loyalty, a strong back, and an automaton-like consistency of execution under near-battlefield conditions.”

In 2003, Erwin bought a restaurant called the Jamaican Jerk Hut, making her a business owner as well as a cook. Working along with her sister, Lisa, Erwin changed the restaurant’s name to Geechee Girl and in 2006 moved its location from the depressed Germantown section of the city to the trendier Mount Airy.

Geechee Girl food has a unique taste. Where is it from?

My mother was from Charleston and my father was from Savannah, so they knew that tradition. My father once said that when he married my mother he thought she knew how to cook, but the only thing she knew how to cook was chicken and rice. I grew up in Philadelphia, and some of the dishes I serve in my restaurant are things we used to have at home when I was growing up: shrimp and grits, for example, or smothered chicken. We used to have “Hoppin’ John,” a traditional rice dish, on New Year’s Day.

You spent several years cooking in big restaurants. What’s the secret to surviving on the line?

The No. 1 thing is to be prepared. You have to have your station prepped before the rush begins, because you won’t have time to prepare everything as it’s needed. ... You have to be fast when you’re cooking on the line, but it’s more about physical organization than about lightning speed. You also need a thick skin. There can be a lot of yelling.

What is your typical workday like?

On most days I get to work at about 10:30 a.m. In addition to doing my prep work, I do a lot of ordering of food and supplies that we will need. I have to pay bills. We close at 10 p.m. and serve our staff meals after the customers have left, so I’m here until about 11:30–12:30 on the weekends.

What is the secret to making perfect rice?

If you like your rice fluffy, you need to rinse it before you cook it and use more water — a ratio of two parts water to one part rice. Whole-grain rice takes more water. Short-grain rice, such as Japanese rice, takes less water and it tends to be less fluffy. You have to practice until you really get a feel for it. But buy a rice cooker instead. That’s the easiest thing to do. It’s not impossible to make perfect rice on the stove, but it is a lot trickier.

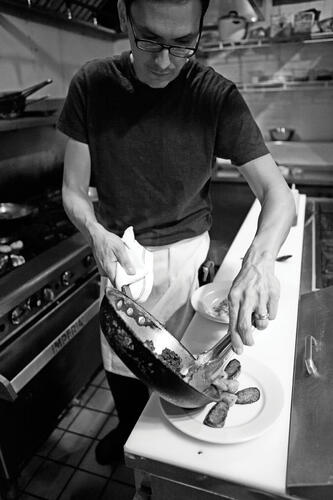

Guy Hernandez ’88

Ask Guy Hernandez ’88 the derivation of the name for his restaurant, Bar Lola, and you get several possible answers. It might come from the title of the Kinks’ song, “Lola.” It might come from the temptress in the musical, Damn Yankees (“whatever Lola wants, Lola gets”). It might come from the pet name given to his Filipina grandmother. But then, Hernandez confesses that he and his wife, Stella Poulis Hernandez ’88, gave it the name because “it just felt right.”

There is something to be said for operating by feel, but in fact just about everything else connected with the restaurant has been carefully thought out, which might be expected of a former civil engineer and architect. Hernandez and his wife opened Bar Lola two years ago in the Munjoy Hill section of Portland, Maine. They wanted to open a restaurant, he says, “where you could get a great cocktail and great food.” Their philosophy was straightforward: great ingredients, treated simply. The restaurant features small dishes — tapas-style, though not necessarily Spanish food — so that patrons can sample four or five items without stuffing themselves and without breaking their budgets.

Guy and Stella met at Princeton. After attending graduate school in St. Louis, they worked for a while in their fields — Guy as an architect, Stella as a management consultant. Then, sitting in a friend’s bakery one day, the couple began plotting career changes, jotting down all the careers they could think of on the back of index cards. To their surprise, cooking kept coming up. Hernandez tested the idea of this new career by working in the bakery. Three years ago, when they got word of an available location for a restaurant, they “jumped off the cliff.” Bar Lola looks exactly the way Hernandez had first sketched it.

Do you accommodate patrons who want dishes made to their specifications?

We do, but it’s not always easy for me, which I think is why I’m in the kitchen and Stella works in the front of the restaurant. I wish some of our customers understood that we have thought through the elements of each dish very carefully. This dish comes with couscous and that dish comes with potatoes for a reason. But we do try to accommodate special requests to a certain extent. In truth, I think both sides, the restaurant and the customer, should lighten up a little. ... Dining out is more about what you experience than any one ingredient in a particular dish.

Can you recommend any of the cooking magazines?

Saveur – that’s the one I wait for.

What basic equipment should every chef have in the kitchen?

Let’s see — a good, sharp knife. A good pan. And a spoon, because you have to taste everything. You should taste your dish, say, before you add salt and then after. That’s how you begin to understand how flavors interact. But take a dish like paella. The only equipment you need to make it is fire and a pan. Everything else is secondary.

How do you experiment with new recipes?

A lot of that kind of development occurs in the kitchen at the restaurant as we prepare each day for service. You focus on, say, a confit or a sauté. You set up your prep stations in the kitchen with different types of ingredients — different tastes, different textures; hot things, cold things. Then you start putting things together and seeing how they taste. A lot of it is seeing what feels right. I try not to overly intellectualize the process. If a recipe calls for apples, you might try it with a pear instead. Maybe you find that a pear doesn’t have exactly the right texture, so you try the next thing.

Kate Zuckerman ’93

Kate Zuckerman ’93, who has been the pastry chef at New York’s Chanterelle since 1999, is gaining a wider audience. In 2006 she published a cookbook, The Sweet Life: Desserts from Chanterelle, to positive reviews, and two national magazines have named her one of the top pastry chefs in the country.

The old kitchen classic, The Joy of Cooking, provided some of her first childhood cooking lessons, Zuckerman says, along with two older brothers (“a real audience,” she calls them) for whom she used to bake. At Princeton she joined Terrace Club but became an independent in her senior year, preparing simple dinners such as soba noodles with scallion vinaigrette for herself and her roommates. Even as an undergraduate, Zuckerman says, she liked to visit nearby farms to pick the freshest locally grown fruits and vegetables, something that has made her receptive to calls for more environmentally friendly cooking practices.

Zuckerman graduated with a degree in anthropology and toyed with the idea of going on to graduate school, but she took a year off before making a final decision about her career. Cooking professionally seemed a natural thing to try. She began her professional training at Boston’s upscale Biba restaurant, and then had her first pastry experience at the Bentonwood Bakery; she also worked as a pastry chef at such noted restaurants as Picholine in New York and Firefly in San Francisco before moving to Chanterelle in 1999. The New York Times has raved about her “courageously bitter chocolate tart” and described her peanut brittle as “a life-changing experience.”

Do you still prepare all the desserts yourself at Chanterelle?

In the last year or so I’ve become more of an executive pastry chef than a hands-on pastry chef producing the desserts on a daily basis. Most of my time is spent tasting things, giving feedback, and planning menus. At Chanterelle, where we usually change the menu every four weeks, staying on top of what is available in the market is key. Each workday, pastry chefs spend the morning baking desserts that will be served that evening. The second part of the day is spent preparing batters, custard bases, doughs, and candies that will be finished in the coming days. So a lot of the work is simple planning and preparation.

How do you go about creating a new dessert?

Well, for example, I was at my parents’ house for Rosh Hashana and had these delicious dates stuffed with coconut. I hadn’t had dates for a really long time, and I was surprised that coconut went so well with them. I have a fig tree in my backyard that I love to use, so I decided to try to make the recipe with fig leaves, which have a subtle roasted-coconut flavor when infused with cream. So I made a warm date-and-coconut steamed pudding with fig-leaf ice cream.

Has environmentalism influenced your cooking?

Being a chef has definitely made me more environmentally conscious. You see how food is packaged, how growers treat their produce to stop the ripening process if it is going to be shipped halfway around the world. I am totally into localism, which also makes a lot of economic sense. You can get apples flown in from South Africa, but why use them if you can get apples that are grown locally? Sometimes, though, it is difficult to obtain local products. I’ve been trying to get fresh honey from New York State, for example. Local, fresh honey that hasn’t been boiled for hours in order to prolong shelf life has a round, fruity, floral flavor. I can go to a farmers’ market, but it’s a struggle for me to get it from a purveyor in the quantities I need for the restaurant.

Can anyone learn to cook?

Anyone who loves to eat can learn to cook. It’s not about having particular skills, but you do have to like good food, you have to like the way things taste and how they interact with each other. Not everyone likes good food. Some people just like junk food. So I guess I’d say that anyone who loves good food can be a cook.

Joyce Lin-Conrad ’02

Feeding a family of five every evening can be a taxing job for anyone, but even more so when the five are not members of your own family. Joyce Lin-Conrad ’02 works as a private chef for a wealthy family north of Palo Alto, Calif. Her cooking mentor, she says, was her grandmother, who immigrated to the United States from Taiwan in the 1970s. By the time she was a teenager, Lin-Conrad was cooking for the rest of her family, and at Princeton she prepared the dinners when she and her fellow Katzenjammers went on the road.

Lin-Conrad had intended to pursue a doctorate in English, but took a year off and enrolled in the Cambridge School of Culinary Arts in Massachusetts. That led to a job at The Dining Room at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in Boston, where she labored 70 to 80 hours a week in culinary boot camp in a classical French kitchen — “the most difficult thing I have ever done in my life.” Looking for a slower pace after she got married, Lin-Conrad became a private chef and has worked for three families, in Massachusetts, Seattle, and now California.

Being a chef is not the career many people had anticipated for her. “My grandmother still asks if I’m working on my Ph.D.,” she says. Eventually, Lin-Conrad says, she hopes to open a cooking school for children and promote better childhood nutrition.

What does a private chef do?

In a way, it’s a part-time job. I work from noon until about 6 or 7 p.m., five days a week. I cook dinner for the five members of the family each night, and I’m also responsible for the management of their kitchen. I do all of the grocery shopping, and I’ll make salads for the next day. And I do a lot of baking — things like cookies or granola bars. Two members of the family have celiac disease and need foods that are gluten-free, so there are some special dietary needs that must be considered. I also cook for the parents’ high-end dinner parties when they entertain their colleagues and friends.

What’s a typical menu?

Let’s take what I prepared for the family last night. They started with roasted pumpkin soup, then had chicken with a Thai rice noodle salad and roasted broccolini.

After cooking a full meal for someone else’s family, what do you eat when you get home?

I try to do a pretty good job for my husband [Mark Conrad ’01] and me, but it is definitely on a dialed-down basis. I tend to prepare much faster stuff, like pan-seared fish and roasted vegetables.

Many families have trouble finding the time to cook. Can you offer any advice?

I would encourage families to set aside just two hours on the weekend and do it together. Making your own granola bars, for example, is easy, and it’s healthier than buying them in the store because people tend to use much healthier ingredients in their own cooking. No one puts preservatives in their own baking, right? Little things like that can make a big difference.

How is being a private chef different from working in a restaurant?

I think you learn a lot of different skills, working in a family’s kitchen. You learn how to work with your employer, for one thing. It’s very interesting being, in essence, a domestic servant; you get an almost anthropological understanding of how people interact with each other. On my best days, though, I feel like I am getting paid to do something that I love.

Peter Nowakoski ’90

When Peter Nowakoski ’90 was a second-grade student growing up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, his teacher assigned an art project. All of his classmates drew pictures or constructed models. Nowakoski made a lemon soufflé. He tried to take the soufflé to school on the cross-town bus. “It never made it,” he recalls sadly.

That might have been the end of his budding culinary career. Although he held several food-related jobs while at Princeton, from working in the kitchen at Chuck’s Spring Street Café to delivering pizzas, Nowakoski quit his eating club after a year to take his meals “here and there” as an independent. (He confesses to having kept an illegal hot pot in his dorm room.) After earning a graduate degree in linguistics at the University of Montana, Nowakoski was finishing his doctorate at Emory University in Atlanta when he confided to his adviser that he was unhappy with the prospect of teaching. “Take a year off and find yourself,” the adviser suggested. Nowakoski flew to London and enrolled in the famous cooking school, Le Cordon Bleu.

With a firm training in the highest French cuisine, Nowakoski returned to the United States in 1999 and found his way back to the Princeton area, to Rat’s Restaurant, located in Hamilton, where he is now the executive chef. Rat’s, which is named for the character in the children’s book, The Wind in the Willows, is located at the Grounds for Sculpture arts center and features five dining rooms, a piano lounge, and a casual café, as well as a thriving catering service.

What is the secret to being a good chef?

The word “chef” in French simply means “boss.” So you can be the chef of a kitchen, the chef of an office, you name it. I don’t think it’s possible to be a good chef without being a good cook, but if you want to succeed in a restaurant, you also need to be able to understand the business side of things. You need to be able to read profit-and-loss sheets, you have to have at least a basic understanding of accounting, and you need to understand how to structure a menu.

How do you structure a menu?

Our cuisine at Rat’s is what I would call well-traveled French, so everything is done by hand. We do a lot of our own butchering, for example. I still seem to have a lot of academic influences, so when I’m thinking up new ideas for the menu, I like to brainstorm. For fall dishes, to take a recent example, I’ll sit down with a piece of paper and try to write down everything that pops into my mind when I think of autumn. Apples. Venison. Wild rice. Cranberries. And so on. Then I’ll try to think of combinations for some of those ingredients.

How do the seasons affect your menu?

We try to change our menus quarterly. Being in New Jersey, everyone likes tomatoes, but some restaurants offer “fresh” tomatoes on their menu in June when they’re not really good until August. I won’t put them on my menu that early; it would be irresponsible. So I’ll look for other fresh, seasonal dishes I can add instead, like baby greens.

You own two or three thousand cookbooks. Which are your favorites?

One would be Julia Child’s The French Chef Cookbook (1968). I grew up with that one. My own copy is all dog-eared and sticky. Julia Child’s The Way to Cook(1989) is another terrific basic cookbook, because it illustrates everything. My favorite cookbook that has come out in the last several years would be Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall’s The River Cottage Cookbook (2001).

Mark. F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

1 Response

Owen Mathieu ’66

10 Years AgoFood and ethics

Thank you for your interesting articles on Princetonians and food in PAW’s Food Issue Nov. 19. Eric Schlosser ’81 spoke at Reunions in May 2006. I told him that until I read his book Fast Food Nation, the scariest book I had encountered was Deliverance. Also, though he is not an alumnus, no discussion of food and Princeton is complete without at least a mention of Professor Peter Singer’s remarkable book, The Ethics of What We Eat (with Jim Mason, Rodale Inc. 2006). This thought-provoking work should be on the reading list of anyone who is concerned about the safety, nutritional value, and/or the ethics of our food choices.