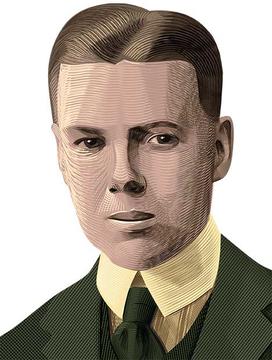

Harvey Smith 1917 Invented a Legendary Princetonian

Princeton Portrait: Harvey Smith 1917 (1895–1969)

One fateful day in January 1936, Harvey Smith 1917, the secretary for his class, found himself with nothing to write for this magazine’s Class Notes. “It is an irreparable blot on the class’s escutcheon to have the Weekly appear without any class news. Some classes haven’t missed an issue in over half a century,” he later said. By evening, Smith’s deadline, his classmates had given him a big fat goose egg: “During the day I had called every classmate I could get on the phone and it was always the same answer, ‘Sorry, old man, I wish I could help you, but I can’t think of a thing.’ Neither could I. My wife had long been in bed, and I had sat in front of my typewriter staring at a blank sheet of paper for hours. I had scratched my head endlessly, but nothing came out of it. Then, suddenly, whoever it is who watches over class secretaries tapped me on the shoulder.”

Smith invented a new member of the class: Adelbert L’Hommedieu X. Hormone 1917, Bert to his old classmates, a rogue, adventurer, and infinitely loyal son of Nassau. An executive at Anderson, Davis & Platte, an advertising agency on Sixth Avenue, Smith drew on his knowledge as an ad man to make Hormone the ultimate fantasy of self-gratification. “My class was already middle-aged by then,” he recalled. “Why not have this classmate do what so many middle-aged men would like to do if they weren’t tied down by a family, business, lack of money, and inhibitions?”

Hormone lived in Bali, where he ran a bar (he taught the house band to play “Old Nassau”). His biography included some mundane details for plausibility: He had red hair, had roomed in Edwards Hall, and had been in constant trouble with the deans for undergraduate rowdiness. His letter, which Smith wrote, appeared in the Jan. 17 issue of the Alumni Weekly: “I won’t bore you with my wanderings since leaving Princeton. I’ll just mention a few highlights. In the fall of ’16, following a night with a crowd of Limey sailors in a Marseilles bordello, I woke up to discover that I was a private in the Foreign Legion.” After adventures in Africa, Australia, and Malaysia, he lost two digits in a sailing accident, reaping an insurance payout that he used to open his Balinese bar.

Only slowly — grudgingly — did readers accept that this most storied of Princetonians was only a story.

Readers wanted to believe the fantasy so badly that they ignored the hints that Hormone was fiction. “The entire Princeton family swallowed Bert hook, line, and sinker,” Smith said. “Many of these thousands of contemporaries have stated publicly at one time or another that they remember Bert well in college.”

Smith obliged by building up the story of Bert Hormone over decades of issues of PAW. Hormone lived among the Tuareg peoples of North Africa, got stranded at sea on a rudderless ship, and hunted for rare orchids in the Amazon. He lost a wallet “containing my Legion discharge, Croix de Guerre, a flock of addresses, my second wife’s picture (there was a gal!), my third mate’s certificate, and my life pass to 32 Rue Blondel,” a famous Parisian brothel. He married four times, favoring a marriage robe of orange and black.

Classmate F. Scott Fitzgerald, who recognized the fiction early, kept the hoax going by writing to Class Notes in 1939 that he had attended a football game with Hormone, who had “the same bland innocence of twenty years ago.” Only slowly — grudgingly — did readers accept that this most storied of Princetonians was only a story.

As for Smith, he rose in the advertising business, becoming the head of his firm’s creative department. In 1941, he published a book with Princeton University Press, The Gang’s All Here, that parodies a 25th-reunion book. Hormone appears among the biographies of the class members, who are fictional but recognizable Princeton types. One point of the book was that Hormone lived the life everyone else wished they lived. They played by the rules, and he did not.

Hormone died in 1967, just before he would have been expected to attend the class’s 50th reunion. His wives kept the flowers on his grave fresh with their tears.

1 Response

Pamela Browne

1 Month AgoGrandfather’s Princeton Creation

My grandfather wrote the article about Bert Hormone. I’m impressed.