Heath Pearson *19 Calls For Reimagining Confinement in America

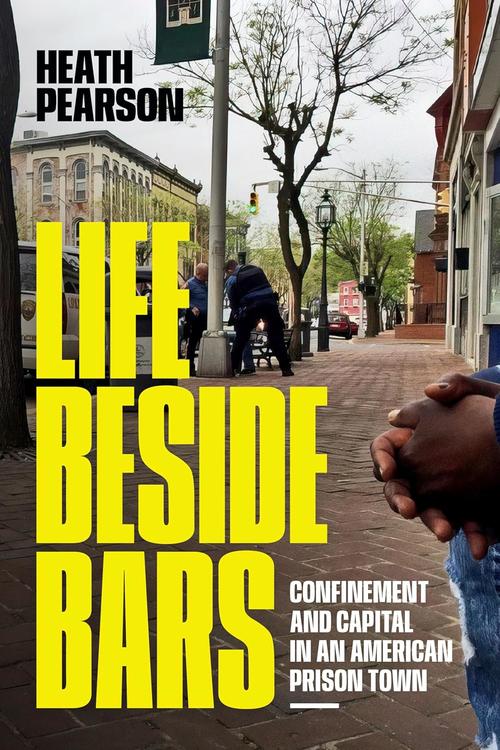

The book: Life Beside Bars (Duke University Press Books) takes readers to Cumberland County, New Jersey — a place defined by its high prevalence of incarceration — to investigate how a tight-knit community is combatting a legacy of confinement. He evaluates the cycle of incarceration from a broad, historical view — taking into account the impacts of native genocide, slavery, racial oppression, and carceral control. The stories contained within the book provide a deeper understanding of the long-term impacts of the modern prison system on American communities — and what these communities are doing to resist those impacts.

The author: Heath Pearson *19 earned his Ph.D. in anthropology from Princeton. He is an assistant professor of cultural anthropology, and justice and peace studies at Georgetown University. He is also the book and media review editor at Current Anthropology. Pearson is currently working on his second book, Streaming Man.

Excerpt:

Introduction - Social Life to the Side

Shakes was sick, so I was on my own for lunch. I jammed the phone into my pocket and drove a few short blocks from the Spot to the Mill, across the street from the county courthouse. The dining room was stuffed with chattering professionals, but the oblong bar had a few empty stools, so I plopped down.

“Are you in a hurry?” the bartender asked, wiping the bar’s surface with a grimy-gray rag.

“Nope,” I replied.

“Good.”

She made her way around the oval bar, snatching up empties, pouring coffee, delivering fresh bottles of beer and plates of food and joking with the white-haired lunch crowd. Ten minutes later, she was back in front of me.

“You’re new in town, huh?”

“Yes,” I replied. “I have been here for about nine months and will be here for another year or two.”

“Why would you move here?” Setting the coffeepot on the bar, a hand on her hip.

I laughed. “Because I am doing research.”

“Ohhhh, I know who you are! I’ve heard of you. You’re here to study the prisons or something, aren’t you?”

“Umm, yeah, I am here to study how the prisons have impacted the area. How did you know that?” I laughed. “Who told you?”

“I-I-I can’t remember,” she stumbled sheepishly, perhaps not expecting the question. “Do you want to hear what I think about how all the prisons have impacted this town?”

“I would love to hear your perspective.” I slid a small, gray notebook from my pocket. “That’s why I’m here.”

“Nada!” Raising a hand in my face in the shape of a zero. “I’m sure that’s not what you wanted to hear, but they haven’t had any impact on this town whatsoever. And I would know — my daughter and two of my sons-in-law work as corrections officers!”

***

The bartender speaks from the side, where regular old workdays, personal opinions, and multigenerational family interests gather in the accumulation of lived experiences that happen in a place called home. Like most residents I met, the bartender never once heard the phrase “mass incarceration” or spent any time scrolling through editorials about the failures of the criminal justice system. Her thoughts on the county’s five facilities were rooted in family relationships, in what they provided for her children and grandchildren, in how they sustained the region, even as the factories and farms fled. For the bartender, prisons were part of the place, like anything else.

Life beside Bars showcases social life in a region with five correctional facilities. The stories take place in Cumberland County, located way down along the southeastern border of New Jersey, where three state prisons — two of which share a working dairy farm — one federal prison, and a regional jail have been squeezed into a 20-mile radius. On any given day, 6,400 people are confined across the five facilities, plus many thousands more on probation or parole. Another 147,000 people live in the area surrounding the facilities. The county has the second-highest concentration of correctional jobs in the country. And this does not include the thousands of people who are employed in the court system, legal offices, social services, prison-adjacent nonprofits, and police and sheriff departments, and the friends and family of those who are confined. As Carl, a local pastry baker in part 1, said to me: “There is a lot of corrections going on.”

This book is about slowing down to spend time with many different kinds of people who have carved out meaningful and sometimes radical social life adjacent to large-scale human confinement. It is easy to think of correctional facilities as institutions that are set apart, tucked away, impermeable, and functioning far outside the activities and concerns of daily life. And for many people across the United States, this may be true — prisons exist somewhere else. But for the millions upon millions upon millions of people who live in close proximity to prisons, who rely on them for employment, who regularly visit, write to, think about, and care for people trapped in them, prisons are a regular feature of social life. My aim in this book is to emphasize close contact with folks who have spent the better part of their lives navigating the spaces that surround Cumberland County’s five facilities. And my hope is that in meeting all kinds of people who occupy the same to-the-side spaces as the bartender, readers will learn something about prisons and their function within one locale, catching a glimmer of the alternative rhythms, a spark of the resilience and resistance, an appreciation for the beauty of social life happening in a place that was developed through the mechanism of confinement.

***

I began fieldwork on the wave of national protesting that marked the early and mid-2010s, supercharged to challenge the owner class and to continue organizing with others toward the abolition of the system of prisons and policing. I also became entangled with prisons and policing on a personal level and learned quickly how confusing, overwhelming, exhausting, and impossible it was to try to support a loved one who was confined or in process. Fighting in the courts, like fighting in the streets, exhausts one to the bones. And my family was ill prepared to face off with the so-called criminal justice system. We were working class with no money, zero extra time, and scant political connections, stretched between multiple low-wage jobs. It was enough simply trying to keep up with the normal demands and expenses of everyday life. Never mind piling on the weight and cost of a loved one’s (potential) imprisonment. So, I wanted to use ethnographic research to connect with others who also had firsthand experiences — people who, from my perspective, had been largely ignored in the wider conversation happening despite their lifelong efforts in developing skills and forging relationships in a landscape dominated by militarized policing and multiple prisons.

I thus set out to write a prison “history from below.” Or, more correctly, to write a prison history from the spaces beside a whole bunch of prisons. I was committed to following the tradition of radical historians, theorists, and anthropologists who took seriously the ideas, the actions, the relationships, and the politics of people who were finding ways to build robust social life within the nooks and crannies of capitalist systems of domination — people who were daily targets of police, who had spent time confined in a prison, or who, perhaps, had friends and family in prison. But, at the very same time, I also wanted to speak with people who benefited — directly or indirectly, intentionally or unintentionally — from the sprawling social, political, and economic possibilities produced by prisons. Because, as with the bartender, if a person was a resident of Cumberland County, then they most certainly had some kind of tangled relationship to the prisons and the policing that helped fill them.

The range of relationships to the prisons encountered in the vignettes that follow, then, are something like the diversity of experiences highlighted by Tania Murray Li among the highlanders of Sulawesi, who, in the 1990s, were introduced to the savage process of capitalism ordering the privatization of their ancestral lands. Many highlanders quickly lost family parcels and thus their present and future livelihoods. Like a plague of locusts, the gobble of privatization chewed across the land, hungry and teeming, laying boundaries over what had been eternally shared and fraying social relationships beyond repair. And, exactly as most people experienced devastating loss and debilitating debt, a few highlanders, some lucky and some shrewd, turned around to find themselves at the top of the hierarchy — more land, better crops, bigger savings accounts, and even able to profit from extending credit to people they once lived and worked with in common.

The same is true of the prisons and the militarized police departments that patrol the streets. The early days of drug war policing hit many by surprise, squarely in the mouth. Officers raided homes, blew up corners, seized vehicles, patrolled school hallways, and targeted young people — especially Black, brown, and poor people — with a supreme viciousness that left so many dead, broken, incarcerated, and sometimes, with the aid of lengthy sentences handed down by the courts, permanently confined and separated from friends and family. As the war clawed along, the prison population grew and grew. But those who were lucky enough to stay out found all kinds of ways to prosper and even build social and political power. Corrections officers in this part of New Jersey, for example, make considerably more in annual salaries than teachers, and they exercise vice-clamped control over certain public spheres, like one of the school boards, where they have held nearly all the elected seats (including president) for almost two decades. Other corrections officers have amassed statewide political power, bending the ears of governors and congress people and media personalities alike. Police officers, who also make far more in annual salaries than teachers, have gained local power, as well as fast cars, access to weapons of death, and, perhaps most importantly, a kind of personal and familial immunity from the attention and surveilling of drug policing itself. Still others, like retired high school teacher Mickey Kite, saw opportunities in snatching up the increasingly available foreclosed or devalued housing while paroled people with few alternatives were suddenly in need of qualified housing. Even the prison-adjacent nonprofits have created wealth and social power for a handful of (mostly white) people. Prisons, like private property, have created cascading economic and political opportunities for a few as they dominate life for the many.

For those who are trapped on the underside of the prisons’ domination, though, it is never the only dimension to their existence. Far from it. Robin D. G. Kelley makes this point in Race Rebels. Beginning in the late-1970s kitchen of a Pasadena McDonald’s, employees who were ridden by the constant surveillance of swing managers and treated as stupid and lower class by the customers developed “inventive ways to compensate” for their exploitative working conditions, like liberating boxes of cookies, making too many burgers and fries near closing time, or offering to clean the parking lot so they could linger outside with friends. Kelley defines these acts as both rebellious and political, and he centers them as endeavors to retain personal dignity while transforming the routinized work of fast food into pleasurable play. Kelley builds on the insights of James Scott and Lila Abu-Lughod, bringing them into a California fast-food kitchen, to argue that these everyday acts of rebellion are, on the one hand, illuminative of how structures of domination reproduce across time and place and, on the other, are instructive in expanding our imagination of what another world might look, feel, and sound like.

This, too, is similar to what I found scattered across Cumberland County. Tucked into the everyday grind of the region’s relentlessly hostile landscape were sparks of resistance and bursts of joy, spaces that were momentarily broken open for sharing, supporting, laughing, and communing and collective acts that at times conjured momentary alternative worlds swaying to rhythms all their own. Like old-school 35- millimeter slides, these tiny moments were difficult to glimpse on their own, from a detached distance with untrained perception, but up close, when sitting in the company of others who knew how to see, hear, touch, and feel them, light passed through to cast into relief a radically different social world not in some grainy, yellow-tinted future but in the very present, nestled right beside systems or moments of domination: a public defense attorney who reconciled with the recently paroled person who murdered her brother, a group of formerly incarcerated men sharing a small business storefront, a young girl riding her bicycle in squealing joy as the family picks up the fractured pieces of life after a devastating police raid. The carceral system of domination in the region remains powerful and merciless but is also incapable of silencing social life, of crushing people into acquiescence, of confining them out of existence.

Instead, folks who were targeted and subjugated in the region, especially those who belonged to families that had lived locally for multiple generations, inherited an understanding of how (their local) domination worked, as well as a cluster of practices for resisting it that had accumulated through decades if not centuries of collective life. Cedric Robinson refers to this accumulation of knowledge, imagination, and practice across privatized space and capitalist time as “the socialist impulse,” which names the persistence of the human spirit to carry on and reinvigorate “visions of an alternative order” irrespective to the political or economic systems working to dominate life and land. For many people I met, their families had been targeted, policed, corralled, confined, and exploited as controllable, exploitable labor across hundreds of years. They had learned tactics of resistance and calculated cunning of the ways the present system of confinement functions, of how police officers actually behave in the streets, of who could be trusted and who could not, from their parents and grandparents, friends and siblings, and of course through their own experiences. Keeping someone free of confinement was a gargantuan collective effort, a local fact as relevant to the present as it had been to the past. This is why I frame the study through the ongoing reproduction of confinement rather than the specific entrance of the prison facilities.

Excerpted from Life Beside Bars. Copyright © 2024 by Heath Person, Duke University Press Books. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Reviews:

“Heath Pearson’s ethnographic voice is tightly attuned to the politics of living, as he deliberately rejects and excises styles and conventions of liberal humanism as a force in tight collusion with capitalism. This is a major accomplishment in and of itself, while his theorization of prisons is powerful. The wild array of stories from characters of all kinds in this carefully crafted book makes a significant point; I learned something of how people live. The effect of this book is visceral.” — Kathleen Stewart, coauthor of The Hundreds

No responses yet