A Hero’s Welcome: Stan Lee at Princeton

The 1966 visit of your friendly neighborhood comics legend

Long before Stan Lee’s standing-room-only talks at comic-book conventions and cameos in the blockbuster movies featuring his characters, the legendary Marvel Comics editor connected with fans in a more intimate forum: the James Madison Room of Princeton’s Whig Hall.

Like many undergrads in the mid-’60s, the Tulenkos grew up reading the formulaic hero comics of the ’50s. Marvel titles were known for “gently mocking the formula” set in place by Superman and his D.C. counterparts, Tim Tulenko said. Lee, the face of the Marvel franchise and creator of Spider-Man and scores of other beloved characters, was an admired figure on campus. A handful of Princetonians formed their own “chapter” of the Marvel fan club, the Merry Marvel Marching Society, and Tim, emboldened by this quasi-official status, stopped by Lee’s office in New York to ask about Blair Hall’s Fantastic Four cameo.

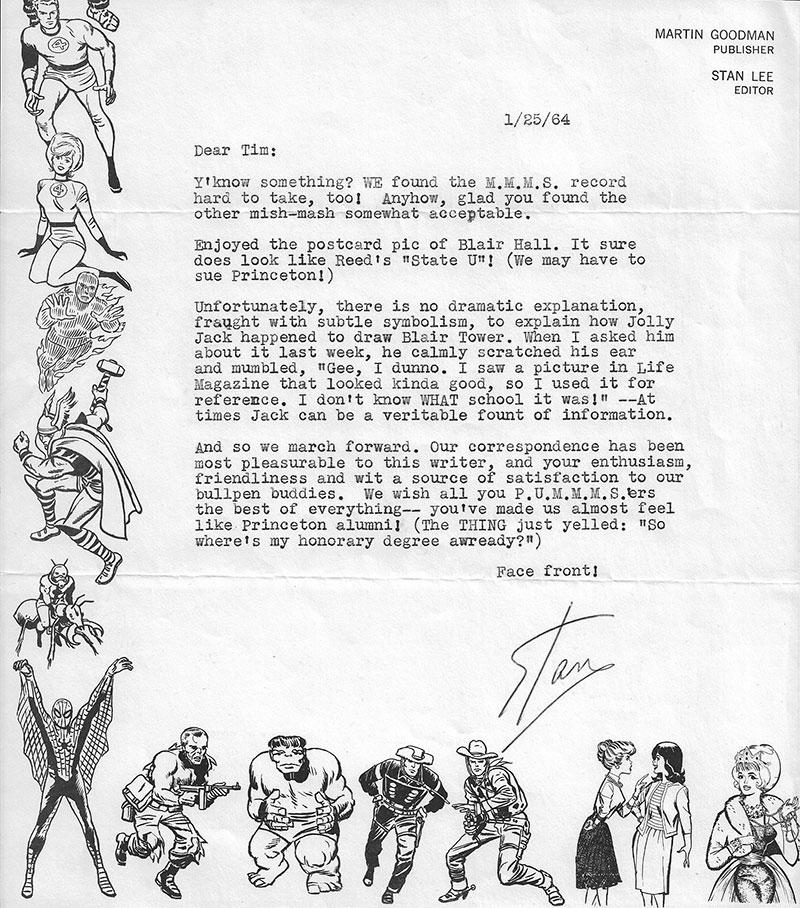

“He was amusedly confused,” Tim Tulenko recalled. Lee wasn’t quite sure what to make of the query; Marvel was publishing a dozen titles at the time, so it was hard to remember the story behind a single page. But soon after the visit, he wrote a letter in reply, explaining that the backdrop was selected by artist Jack Kirby, another Marvel legend, from the pages of Life magazine (see below).

Later that year, the Tulenkos and two friends, Bob Keener ’68 and Clayton Lewis ’66, returned to New York for an afternoon visit and a mock-serious discussion of mythological structures in Marvel books. The visit went so well that the students invited Lee to speak, on behalf of Whig-Clio, and Lee accepted.

A partial recording of the Whig-Clio event is available online, courtesy of author Sean Howe. Lee, who was new to the speaking circuit, gave initial remarks that lasted a mere two minutes and then opened the floor to questions. Soon after, when a student asked him to explain how Norse and Greek gods could coexist in the same universe, Lee deadpanned, “Sometimes these question-and-answer periods go on too long.”

“That’s actually the charm of it,” Tom Tulenko said. “He’s new to the speaking game, and they’re asking him things that he’s never had to think about, but he’s glad to hear the kind of questions that they’re asking — and he’s handling it well.”

Responding to another question, Lee credited his wife, Joan, with encouraging him to improve on the standard superhero tropes. As a result, he’d come to the realization that heroes would be more interesting if they were regular people with extraordinary powers.

“Let’s write stories where the whole idea would be, ‘What would you do if you had super powers?’” Lee said. “And I think this is the reason that the books caught on. I think everybody kind of felt, ‘Gee whiz, we haven’t read this before.’ When the novelty wears off, we might have to start getting cliché-ridden to keep our readers, because after a while, this realism kick may become dull. But until it does, it seems to be doing pretty well.”

A handful of newspapers covered Lee’s visit and quoted reactions from students in the audience. One junior told The Trentonian that he thought of Marvel books as “20th century mythology,” while a sophomore told the Star-Ledger that comics are “as much of an art form as pop art.”

The experience would become part of Lee’s lore (he was known to brag, tongue firmly in cheek, about his honorary membership in “the Cliosophic Society”). But more importantly, it laid the foundation for a career on the speaking circuit. As authors Jordan Raphael and Tom Spurgeon wrote in their 2004 book, Stan Lee and the Rise and Fall of the American Comic Book, speaking at Princeton “led to a flurry of media interest and invaluable word-of-mouth among college-speaker committees.” Lee hired an agent and upped his speaking fee. “By 1975,” Raphael and Spurgeon wrote, “Lee could produce a list of colleges he’d spoken at that read like a bright child’s wish list of prominent universities.”

No responses yet