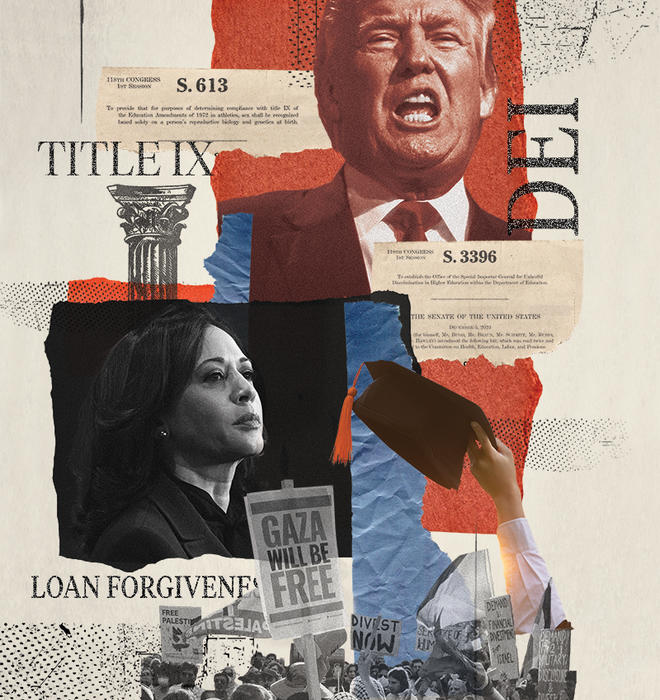

Higher Education on the Ballot

Why this year’s election may be the ‘most consequential’ in a generation for colleges and universities

Mun Choi *92 saw what was going on around his university.

Across the country, the walls were closing in on diversity, equity, and inclusion programs at state schools. In Missouri, members of the general assembly had filed 13 bills to curtail DEI initiatives in the previous two years and had debated adding a ban in the state budget. A Republican candidate for governor even vowed to fire state employees who promote DEI.

Choi, chancellor of the University of Missouri, saw an opening when the vice chancellor who led the Division of Inclusion, Diversity and Equity accepted a job at another school. In August, he announced he would disband the office.

“I think each university has its own set of challenges and opportunities,” Choi, who is also president of the University of Missouri system, tells PAW. “Our decision made sense for us. We were able to play a big role in preventing those bills from passing because we acted proactively.” The office’s employees, he says, were reassigned to other departments and are “continuing to do the work of student success and faculty success.”

The political pressure is likely to escalate for Choi and his colleagues.

Though issues such as inflation and immigration have taken top billing in the presidential campaign, the results in November could leave an even sharper imprint on colleges and universities.

“I think the 2024 election will probably be the most consequential for American higher education in 60 years,” says W. Taylor Reveley IV ’96, president of Longwood University, a public institution in Virginia, and a historian of the U.S. presidency. Reveley was among nine college presidents and experts, most of them Princeton alumni, interviewed by PAW about what’s at stake for higher education in November.

The potential impact could touch areas from Pell Grants and loan-forgiveness policies to DEI initiatives and LGBTQ+ protections. The underlying ideologies pivot on competing notions of justice, responsibility, equality, and compassion.

If Vice President Kamala Harris is elected president, “my guess is that she would follow through on Biden’s policies,” says S. Georgia Nugent ’73, who recently retired after leading three private institutions — Kenyon College and the College of Wooster, both in Ohio, and Illinois Wesleyan University.

“If [former President] Donald Trump has a second term,” Nugent says, “there will be many more attempts to control colleges and universities, as we’re seeing in Florida.”

Attacks from ‘across the board’

Federal involvement in the workings of colleges has grown in the past two decades, says Doug Lederman ’84, editor and co-founder of Inside Higher Ed, a national higher education news publication. He attributes the trend to declining public and political confidence in universities, along with the increasing use of federal mandates. One example: President Joe Biden’s multiple executive orders to cancel student debt.

The Republican attacks tend to be more scathing. But the heightened scrutiny is coming from both sides of the aisle, Reveley and Lederman say.

“There’s different worrying in different ways that’s coming from across the board,” Reveley says. “It’s a wariness that means the years ahead will be years with a lot of change, not just minor ordinary updates.”

Republicans, Lederman says, are targeting what they see as institutions’ liberal tilt, lackluster reaction to antisemitism, and failure to adequately prepare students for jobs. “The Democrats are worried about access and affordability. They think higher education is out of reach for a lot of Americans and is still disproportionally available to people of wealthier backgrounds,” he says.

Both parties are zeroing in on elite universities. “I am finding the highly selective, wealthy institutions to be on the defensive in a way that’s not like anything I’ve seen in 35 or 40 years of covering this stuff,” Lederman says.

Two presidents of Ivy League universities — Liz Magill at Penn and Claudine Gay at Harvard — resigned last winter after facing fierce questioning in U.S. House hearings on their handling of pro-Palestinian protests and their response to Jewish students’ concerns. And a third — Columbia’s Minouche Shafik — stepped down in August after months of turmoil on campus connected to the war in Israel and Gaza.

Princeton avoided congressional scrutiny but remains vulnerable because of its status as an elite institution. Several bills, nearly all proposed by Republicans, including Ohio Sen. JD Vance, the vice-presidential candidate, would increase the tax on university endowments. Princeton’s was valued at $34.1 billion at the start of the fiscal year in July 2023. Income from the endowment accounts for more than half of the University’s annual operating budget.

“At a time when global competitors like China are trying to overtake our lead by increasing their investments in research and higher education, taxing the charitable gifts that help make U.S. colleges more affordable and support breakthrough scientific and technological innovation does not make sense,” says Tobin Smith, senior vice president for government relations and public policy at the Association of American Universities. Princeton President Christopher Eisgruber ’83 is the association’s vice chair.

It’s not just the presidential election that matters.

All 435 House seats and 34 of 100 Senate positions are in contention. If one party takes control of the White House and both branches of Congress, that eases the way for the president to push through education goals, such as Trump’s plan to tax school endowments to finance the American Academy, which would offer free online education, with “no wokeness allowed.”

Likewise, a Republican sweep could propel such bills as the University Accountability Act, introduced in July by 13 House Republicans. It would fine universities at least $100,000 if they were found to have violated students’ civil rights, with an eye toward tamping down antisemitism. If Democrats were in full control, they’d be more likely to push their plans for free community college.

Even more influential to public institutions are the down-ballot state races in which voters select governors and members of legislatures, who in turn appoint trustees of state university boards, says Peter McDonough, vice president and general counsel of the American Council on Education, a major lobbying group for higher education. McDonough previously served as general counsel and staff lawyer at Princeton.

In Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis and the Republican-led legislature have put an “anti-woke” stamp on the state’s public universities, eliminating DEI offices, banning instruction that instills “discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress,” and requiring schools to find new accrediting organizations.

North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper is a Democrat, but the Republican-led general assembly appoints members to the University of North Carolina board of trustees. In May, against Cooper’s wishes, the board repealed the system’s DEI policy, which required schools to hire diversity officers, and replaced it with a mandate to uphold “institutional neutrality.”

Lt. Gov. Mark Robinson, a Republican running to succeed Cooper, has vowed to ensure that “students paying for an education aren’t being force-fed extreme and divisive ideas like DEI or critical race theory, instead of preparing for the workforce.”

Loan forgiveness and Pell Grants

“The federal government actually doesn’t have a huge role in higher education,” says Ann Marcus, director of the Steinhardt Institute for Higher Education Policy at New York University.

The U.S. Department of Education primarily focuses on K-12 schools, but it plays a crucial role for college students in administering financial aid. The College Board estimates that undergraduate and graduate students annually receive more than $240 billion in grants, loans, work-study stipends, and other forms of assistance.

President Biden’s chief strategy to relieve financial burden has been to cancel debt. The Supreme Court and other federal judges have blocked some of his programs, declaring them presidential overreach. But Biden has succeeded in erasing roughly $170 billion of student debt and has proposed further extensions. The Democratic platform vows to provide up to $10,000 in debt relief for borrowers.

The Republican platform does not address loan forgiveness but says: “To reduce the cost of higher education, Republicans will support the creation of additional, drastically more affordable alternatives to a traditional four-year college degree.” Project 2025, the blueprint to overhaul the federal government written to support Trump’s agenda, would eliminate all loan forgiveness programs, including one erasing the debt of people in public-service jobs such as teachers.

More than 49% of families reported borrowing for college in 2023-24, up from 41% in the previous year, according to a recent study from Sallie Mae, one of the nation’s largest private lenders, and Ipsos, a market research firm. The consequences can stretch for decades. The Urban Institute, a Washington think tank, estimated that 6% of older adults are still paying off loans, with some having their Social Security benefits garnished.

Loan forgiveness is “incredibly important,” says Anne Holton ’80, a professor of higher education policy and a former interim president at George Mason University, a public institution in Virginia. “The bubble of debt we’ve gotten ourselves into is absolutely gumming up people’s ability to buy a house, get married, and raise a family. Even small amounts of debt are interfering with their credit rating and ability to participate in the economy.”

Others — and not just Republicans — are less convinced.

Nugent, the former president of three institutions, says the debt crisis has been exaggerated. She notes that more than 40% of graduates have no debt and that the levels of car and college debt are similar. The average car debt for Americans is roughly $24,000. By comparison, the College Board estimates that the average debt for bachelor’s degree recipients is $29,400.

“That’s not nothing for sure,” Nugent says, “but it’s nothing to get hysterical about.”

Lederman, from Inside Higher Ed, describes loan forgiveness as “a Band-Aid that fixes things in the rearview mirror but doesn’t actually do anything to make higher education more affordable. It doesn’t change the underlying economics for anybody going forward.”

To avoid debt, “we need to further educate prospective students and their parents about the options available for a high-quality, affordable education,” says Choi, the University of Missouri chancellor. “I believe strongly in personal accountability.”

At Princeton, the problem is far less profound. The University most recently announced expansions to its financial aid program in 2022, covering tuition, room, and board for students from families that earn up to $100,000 annually. As part of its 2023-24 budget, Princeton estimated that the cost of attendance for the average scholarship recipient would be about $13,000.

But at many other schools, students rely on other forms of aid, most notably Pell Grants. Eisgruber and other presidents have called for significant increases to the federal program, which was created in 1972 to help low-income families.

During Biden’s term, the maximum annual Pell Grant has risen about $1,000 to $7,395. The Democratic platform advocates doubling that amount and eliminating tuition at public colleges for families with incomes below $125,000.

Neither Trump nor any of the Republican position papers mention Pell Grants. But Reveley, the presidential historian, warned not to assume that Trump or a Republican Congress would ignore the program.

“Silence can be overread,” says Reveley, whose father, W. Taylor Reveley III ’65, is a former president of the College of William and Mary in Virginia. “There’s pretty genuine bipartisan support” for Pell increases.

What’s next for DEI?

The candidates’ words showcase their sharply contrasting opinions on diversity.

Harris: “Our unity is our strength, and our diversity is our power. We reject the myth of ‘us’ versus ‘them.’ We’re in this together.”

Trump: “We will eliminate all diversity, equity, and inclusion programs across the entire federal government.”

Project 2025 calls for stripping DEI requirements and references to sexual orientation and gender identity from “every federal rule, agency regulation, contract, grant, regulation, and piece of legislation that exists.”

If Republicans gain control in Washington, Lederman says, “there will be unbelievably strong anti-DEI rhetoric and there will probably be attempts to nip and tuck here and there, but I think that’s as far as it can go.”

Other higher-ed analysts also discount the possibility of widescale anti-DEI federal mandates, but they say the pressure could prompt universities to follow Missouri’s lead and curtail DEI initiatives to keep the politicians away.

The Chronicle of Higher Education has tracked DEI pullbacks at 196 campuses in 29 states as of early September. They range from the widespread closing of DEI offices and abandonment of diversity hiring statements to the cancellation of new diversity-themed classes at two Virginia universities — George Mason and Virginia Commonwealth — because of board concerns.

At Princeton, Eisgruber has repeatedly stressed his commitment to diversity.

“A noxious and surprisingly commonplace myth has taken hold in recent years, alleging that elite universities have pursued diversity at the expense of scholarly excellence,” he wrote in The Atlantic this year. “Much the reverse is true: Efforts to grow and embrace diversity at America’s great research universities have made them better than ever.”

DEI “isn’t just about race,” says Holton, who also served as Virginia’s secretary of education. “It’s about low-income students, first-generation students, or students from any cohort not traditionally well-represented in higher education. Having a posse of students who come from similar backgrounds to support each other contributes to their chances of success.”

She warns against mandates to remove curricula: “There are so many topics one cannot properly address without talking about race. That’s true in anything connected to American history and civics.”

Nugent says, “Obviously, trying to achieve some kind of equity and parity across individuals and groups has a positive impetus, but the devil is in the details. There have been tremendous advances in the composition of the student body, but it’s very hard to modulate people’s behavior in regulatory ways.”

Two sociologists — Frank Dobbin from Harvard and Alexandra Kalev from Tel Aviv University — concluded, “Hundreds of studies dating back to the 1930s suggest that antibias training does not reduce bias, alter behavior, or change the workplace.”

Khalil Gibran Muhammad, Ford Foundation Professor of History, Race, and Public Policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, says, however, that research points to a positive track record for DEI in higher education.

“Improving accountability, equity, and overall campus climate strengthens a university’s mission of academic success,” he said last year. “Those schools that don’t or can’t because of political interference are simply going to lose out on recruiting the best and brightest young faculty.”

Betsy Levy Paluck, the Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology and Public Affairs at Princeton, says more intensive study is required. In a 2021 article in the Annual Review of Psychology, she wrote: “We conclude that much research effort is theoretically and empirically ill-suited to provide actionable, evidence-based recommendations for reducing prejudice.”

Title IX twists and turns

The 1972 law banning gender discrimination in education empowered victims of sexual assault and harassment and strengthened women’s athletics on campuses. But in the past decade, the higher education community has been frustrated by the changes in Title IX regulations between Republican and Democratic presidents.

President Barack Obama added protections for LGBTQ students, which were supported by colleges and universities. They were rescinded by Trump and recently restored by Biden, but federal judges have blocked the latest version in 26 states, leaving universities in limbo. (The Biden version does not address the status of transgender athletes competing in collegiate sports.) If Trump wins, he’ll likely strip those provisions.

Those wouldn’t be the only changes. There’s also been back-and-forth on the logistics for investigating and adjudicating sexual assault cases on campus, with shifting balance between the victims and the accused. Trump added requirements for live hearings with cross-examination and narrowed the scope to on-site incidents. Biden whisked those away, also lowering the standard to determine guilt.

Ted Mitchell, president of the American Council on Education, which represents more than 1,600 schools and associations, has been a proponent for removing the mandates for hearings and cross-examination, which he said often “turned those proceedings into adversarial, court-like tribunals, raising concerns about potential retraumatization for survivors and creating an undeniable chilling effect on their willingness to come forward.”

But Samantha Harris ’99, a lawyer in Philadelphia who specializes in campus free-speech and Title IX issues, says it’s a turn for the worse. “I don’t think the right to a fair process is something that is anti-victim,” she says. “Whether my client is an accused student or a claimant, having a more robust process benefits the truth.”

Even supporters of the latest revisions grumble about what the American Council on Education’s McDonough calls “the whiplash effect.”

The constant changes “require much more time for planning and detract from facilitating the fundamental purpose of Title IX, which is to make sure people’s pathway through education is free of discrimination,” says Reveley, Longwood’s president. “The regularity of the process arguably might exceed the importance of any particular provision in it.”

International students

Universities fear Trump’s anti-immigration rhetoric could depress international enrollment. As president, he executed a series of travel bans targeting countries with large Muslim populations.

In a surprising softening of tone, Trump said in a podcast in June that foreign graduates of U.S. colleges should receive green cards, allowing them to stay in the country. However, campaign spokeswoman Karoline Leavitt subsequently clarified that Trump would exclude “communists, radical Islamists, Hamas supporters, and America-haters.” Project 2025 vows “to eliminate or significantly reduce the number of visas issued to foreign students from enemy nations.”

The Democratic platform, in contrast, promises “to restore trust and certainty for international students and the higher education sector.”

Foreign enrollment in the United States held steady during the beginning of the Trump administration but declined 15% in 2020-21, coinciding with the onset of the COVID pandemic, according to federal data. Enrollment has since risen, but the total — 1,060,000 — is still below the previous peak of nearly 1.1 million. At Princeton, after a big decline from 2020 to ’21, international enrollment jumped back to its previous level of about 2,050. Roughly two-thirds are graduate students.

McDonough hopes the numbers keep going up. “We’ve had so much innovation, so much experimentation that has been triggered by or helped by foreign-born individuals who have come here to be educated,” he says. “We need to continue to be a place that is seen as a destination, and that strikes me as a big deal.”

Philip Walzer ’81 covered higher education for 20 years for The Virginian-Pilot. He retired this year as the alumni magazine editor at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia.

1 Response

Hannah Reynolds Martinez ’22, Lynne Archibald ’87, and John Huyler ’67

1 Year AgoAnother Preemptive Action?

Two recent pieces, “Higher Education on the Ballot” (October issue) and “Princeton to Accept Certain Fossil Fuel Funds” (November issue), might be connected. The first discusses challenges facing elite universities: “‘We acted proactively’: Mun Choi *92 eliminated the DEI office at the University of Missouri, he says, to head off political pressure.” Choi lays out how public universities quietly dismantled their DEI departments ahead of a possible Trump win.

In the November issue, there is the report on Princeton thumbing its nose at its own process by suddenly gutting its fossil fuel dissociation policy. This was an unexpected reversal of the University’s tentative yet encouraging move away from fossil-fuel-funded research. At a Council of the Princeton University Community meeting, President Eisgruber ’83 noted that Princeton was the only American university with such a policy. It was also stated that there aren’t any projects needing fossil fuel funding from dissociated companies now. Did President Eisgruber wish to preemptively take the “dissociation target” off Princeton’s back?

As On Tyranny author Timothy Snyder wrote, most of the power of authoritarianism is freely given because people think about what a more repressive government will want and then just do it. It is disheartening that Princeton will not stand by its own principles with respect to the climate crisis. If the worst is true, it is deeply disturbing that Princeton, a private university with the largest per capita endowment in the world, is willing to jettison its students’ futures in order to prostrate itself before the new administration.