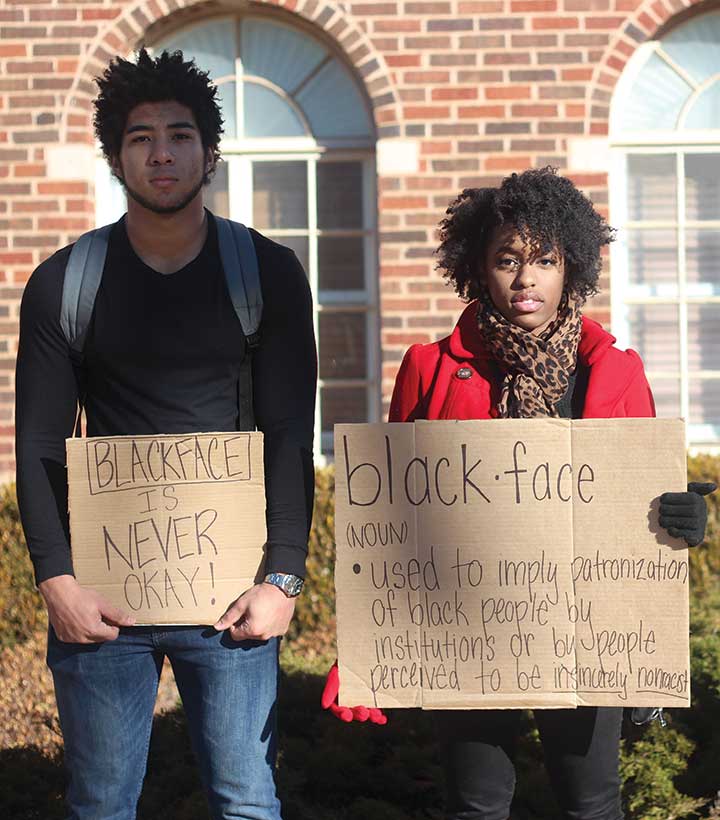

History: Rhae Lynn Barnes on an American Stain

A Princeton scholar explains the insidious and pervasive history of blackface

What are the origins of blackface minstrelsy?

Blackface is a makeup technique that’s been used for hundreds of years — think Shakespeare’s Othello. But in terms of blackface as we understand it today in the United States, you have to look to the Jacksonian era. Starting around 1828, a white celebrity named T.D. Rice began performing as the character Jim Crow. His song was called “Jumpin’ Jim Crow.” It globalized very quickly — he traveled to perform throughout the British Empire — and became very popular.

In the 1840s, we see the rise of the Virginia Minstrels, which is the group that created the three-act minstrel show. This show was an entire evening of blackface entertainment, as opposed to being a one-off character or dance performance. Throughout the show you’d have classic American music by the songwriter Stephen Foster — songs that we still know today like “Camptown Races” and “O! Susannah.” And it was tremendously popular. In the 19th century, blackface was seen as the No. 1 entertainment form and the U.S.’s major contribution to global popular culture.

How did it evolve after the Civil War?

There’s this idea that by 1900, blackface minstrelsy is subsumed into vaudeville and later radio, film, cartoons, television. But as technology advances in the 20th century, the omnipresence of blackface only increases. The difference is that it’s mainly amateur blackface, rather than professional theatrical blackface, which is a separate and distinct genre. For most of the 19th century, blackface was centralized in New York City — you’d have to go there to see a minstrel show. But a fraternal group called the Elks Club is founded in 1868, and they begin publishing their own scripts for these shows, which transforms the people who used to just watch blackface minstrel shows from passive consumers into active participants. They start putting on their own shows. And this pro-slavery, white ideology is then passed down through these scripts, which are sung and performed across the country in the 20th century.

What were some of the themes of these shows?

The thing all of these shows have in common is very romantic ideas about Southern life and slavery. The shows aren’t linear — they’re a series of sketches, like a variety show — but usually an African American character will try to do something like use a telegraph or a telephone or get on a train. Then they make a mistake that’s obvious and silly, and they end up getting maimed or killed. It entrenches these characters as Southern, dim-witted, not understanding technology, not being able to fend for themselves in the world at a moment when millions of African American people are getting educated and moving to urban areas and obtaining professional jobs. It undermines this tremendous progress that’s being made by African Americans.

Blackface minstrel shows were based in New York? Wasn’t this a Southern phenomenon?

I’m always surprised by how many people associate blackface with the South, because it is not a Southern phenomenon at all. It originated in New York. Southerners didn’t really bother with it because during slavery, white people had access to African Americans that they owned. It was completely a Northern creation, and it was also very popular in the American West.

Why did blackface performances remain so popular?

You have to remember that it was seen as the U.S.’s unique contribution to global culture, so it was always considered patriotic. That’s confusing for us today, but that’s how it was seen through Jim Crow and up until the civil-rights movement. In the 19th century, minstrels performed in front of the American flag wearing red, white, and blue. The songs are very patriotic. And the shows were seen as a clean form of fun — appropriate for all ages — in that there was nothing sexually scandalous going on.

What were some of the venues where white Americans in the 20th century might have seen blackface shows?

People were exposed to it at multiple points in their lives. School curricula would use Stephen Foster songs as representations of authentic African American music. Fraternal orders like the Elks put on their own minstrel shows. During World War II, the federal government was mobilizing it for the troops. There were productions at colleges, in fraternities. And many politicians were participating by viewing blackface minstrel shows as a way to galvanize and connect with communities.

How does this history connect with the scandal in Virginia?

Today, we’re talking about blackface costumes and not blackface minstrel shows. But we do see it re-emerging in the South in the 1970s as a backlash to the civil-rights movement. And I think we have to remember the history here, especially that blackface is not a product of the South.

That forces us to grapple with the fact that there was also a Jim Crow North and West that might be just as powerful as the Jim Crow South, but manifested in a different way — redlining, rather than segregation. The persistence of blackface minstrelsy is a reminder of how deeply these racist stereotypes were institutionalized in American life.

Interview conducted and condensed by Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux ’11

No responses yet