History: Trenton in the ’60s

A research and civic-engagement project delves into an uprising and its aftermath

After arriving at Princeton in 2010, Isenberg began to answer those questions. Having learned that The Times of Trenton archive was searchable through Princeton’s databases, she researched Joseph’s life. Though just 19 when he was killed, Joseph had led a full life in which Princeton University played an important role. Isenberg’s inquiry led her to launch the first in-depth study of the 1968 Trenton riots and uncover information that raised questions about long-held perceptions of what had happened that day. Her work also has provided uncommon research opportunities for undergraduates.

Joseph was shot on the evening of April 9, 1968, following King’s funeral, in front of a store that had been looted. Police described him as a looter because merchandise from the store was scattered near him, but Joseph was a sophomore at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and a member of the Trenton Mayor’s Youth Council. Through research conducted over the last four years — including interviews with dozens of Trenton residents — Isenberg found he had in fact been working to keep the peace. The officer, who was white, said the shooting was an accident, and he was cleared by a police investigation, according to The Times of Trenton.

Isenberg’s curiosity to learn more about Joseph has helped to establish The Trenton Project — a research, teaching, and “public humanities” collaboration with Purcell Carson, a documentary film specialist at the Woodrow Wilson School — that focuses on the intertwined Trenton-Princeton region in the 1960s. So far, more than 50 students have conducted research using primary sources as part of the project.

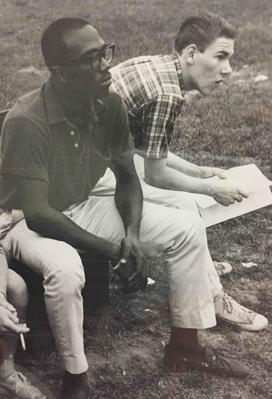

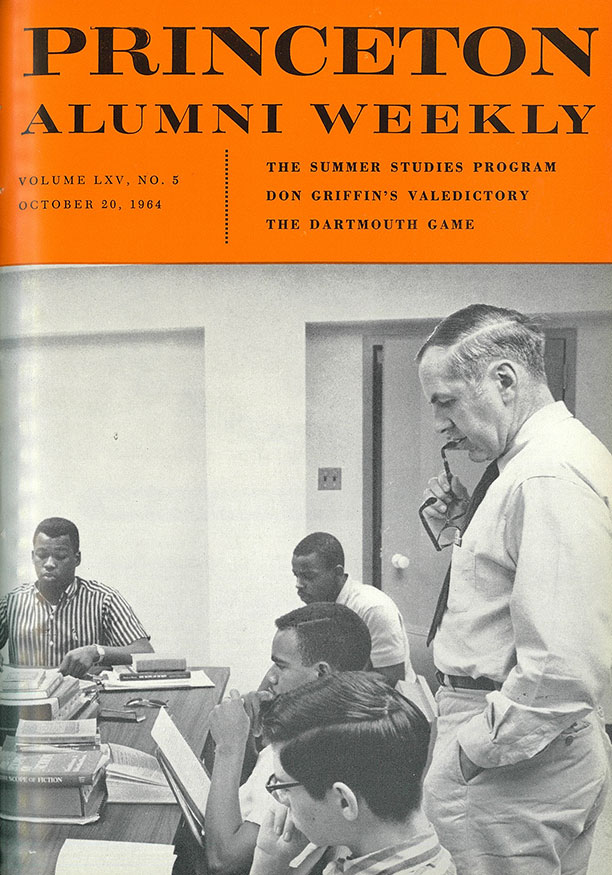

Isenberg learned that Joseph had spent the summer of 1964 as a participant in a little-known Princeton program that brought 40 New Jersey high school students from minority communities to campus for a summer course of study. It was an important turning point in his life, according to Joseph’s letters and accounts from his siblings, that helped improve his writing skills and awaken his interest in organizing against racial discrimination.

In 2018, Isenberg taught a seminar called “Performing the City: Race and Protest in 1960s Trenton and Princeton” with lecturer Aaron Landsman. Students in the class mined archival material on race and protest in the 1960s to examine how those issues intersected with Princeton. In “Documentary Film and the City,” co-taught with Carson, students made seven- to 10-minute movies that focused on Trenton, using the 1960s as a historical lens. History classes rarely include a filmmaking component, and undergraduates outside of film schools usually do not get the chance to produce their own short movies, Isenberg says.

Students have delved into records that have been tucked away for decades. “There is so much historical material nobody has looked at, and we are finding it in basements and attics,” says Isenberg, who took students to examine 80 boxes of records that had been forgotten in the basement of Mercer Street Friends, a Trenton nonprofit where Joseph had worked organizing youth programs. One student discovered a letter written to The Times of Trenton by the organization’s president asking the newspaper to stop referring to Joseph as a looter.

Students also have worked with the Trenton community extensively for their films, interviewing shop owners for a look at how downtown has changed in the last 50 years and talking to longtime residents to examine urban renewal in the Coalport neighborhood. The films have been screened at ArtWorks in Trenton, often drawing audiences of more than 100 residents who offer feedback and reflections on what they have seen.

“We’ve done deep dives into very specific corners, communities, and issues in Trenton,” Carson says. “When we’re at our best, I think The Trenton Project has been successful. I sense that most strongly when people are gratified by participating, moved by the results, inspired to talk about and share the films — and, more broadly, when they see how their neighbors’ stories connect to their own lives.” Carson and Isenberg are in the final stages of completing a 30-minute documentary centered on the untold story of Joseph’s life and the Trenton uprising, and Isenberg also is writing a book. Their film disputes the notion that the subsequent economic decline of the city largely hinged on the damage done that night by angry citizens.

Watch student films about Trenton history at thetrentonproject.com

Using police and fire records, interviews, and newspaper accounts, the researchers found that fire and property damage was actually “a fraction of what was originally reported. As in many U.S. cities, Trenton’s ‘riots’ became a simplified explanation for that city’s economic struggles since the 1960s,” Isenberg says. “Many of Trenton’s deepest problems — deindustrialization, the relocation of retail business to the suburbs, structural racial inequities, and the massive destruction achieved by Trenton’s urban-renewal projects — date to the 1950s and earlier.”

Isenberg says her investigation into what happened on the night Joseph was killed — and the way she has connected her work to the Trenton community — demonstrates how historical research can contribute to current conversations about the city’s future. “I would like this work to address some misconceptions about the city in 1968 and create just enough space for new stories about the past to take hold,” she says. “We can’t know where those stories are going to take people. But Harlan Joseph’s life, on its own terms, is an inspiring and empowering example.”

A Walk Through 1960s History

A class project assigned by history professor Alison Isenberg on student life in the 1960s offered the family of Javier Johnson White ’67 — who died at age 42 after a lifelong illness — a chance to meet and reminisce with his friends from his college days for the first time.

Maria Jerez ’19 researched White’s life — his experience as an undergraduate and as a counselor in a little-known University summer program for minority students — for the class “Performing the City: Race and Class in 1960s Trenton and Princeton,” co-taught with lecturer Aaron Landsman. Jerez, who chose White because she was interested in understanding the experience of a Hispanic student at Princeton, created a historical walk through campus that offered details of his life in the spots that were significant for him.

White, along with many of Princeton’s small number of black undergraduates, worked for the summer program’s first session, in 1964, and spent six weeks mentoring high school sophomores to help prepare them for college. One incident from the summer remains etched in Dawson’s mind. When he and a few other African American summer program students visited a barbershop on Witherspoon Street, the barber told them he didn’t have the right kind of clippers to cut black hair and suggested they go to a different shop. That experience awakened his understanding of racial injustice, Dawson says. He remembers the counselors, especially White, urging the students to organize and protest being refused service.

“We didn’t think we should challenge authority,” Dawson says. “But Javier told us, ‘That’s what students do. It’s up to you to change things.’ We were really inspired by him.” The students wrote a letter to the Town Topics newspaper, and the mayor of Princeton and University President Robert Goheen got involved in the controversy on the high school students’ behalf.

The group paused at McCosh Health Center, where Jerez read from medical records that referred to White missing exams after a stay in the infirmary, part of his lifelong struggles with complications from rheumatic fever.

“I’m honored to be here to find out more about a man I didn’t really know,” says Javier White, his son, who was 9 when his father died. Bernstein presented White’s family with a photo of their father at the drums during a concert. The two friends played together for four years as members of the Quorum, a jazz band. “There’s always been a gap in our understanding of what his life was like here,” says his daughter, Naomi White Randolph. “But we are filling it now.”

1 Response

Rev. George A. Bates ’76

6 Years AgoDiscovering the Truth

In reflection of the “Trenton in the ’60s” article about Professor Alison Isenberg and her students, the gauntlet is being sounded to one inescapable fact — we as a nation cannot move forward until we examine and discover the truth behind America’s ugliest explosions of violence during the 1950s, 1960s and 1970’s. Once we get that, then we need to put forth honest solutions to change America from the inside out. The Kerner Commission report of 1968 began the discussion that the following factors contributed to these macro-bursts of anger, hatred and violence: 1) As blacks fled the racial killings and hostilities of the South from 1920 to 1970 and flooded into the Northern cities, the “town fathers” had no plan for their acceptance and inclusion. 2) The ghettos of American cities grew rife with no education, poor education and mis-education, drugs, illegal weapons, prostitution, illegal gambling, unregulated housing, speakeasies and dance halls and social activity that was an “unwanted” appendage to white America. 3) White America was vehemently opposed to learning anything about the new arrivals who were fleeing violence and abject poverty in the Southern states. (This is the same plight that the Latino Americans are experiencing that has prompted them to make the risky trip north to the United States.)

Consequently, the decrease in the distance of rural Southern black America from hundreds of miles to a few blocks has made our Northern and West Coast urban cities “uneasy” powder kegs that would explode at the least bit of agitation. The inner cities of the 1960s were “perfect bombs” — uneducated and poorly skilled people compressed into communities with no upward opportunities sandwiched between wealthier white neighborhoods. Both camps “equally estranged” and forbidden to learn of each other by the social constraints of a centuries-old racial history with no vehicle to “release” the simmering tension. City Hall, social services, juvenile halls, the police departments, white and black churches and civic groups were all total strangers to each other. Our educational system absolutely refused to teach whites about blacks, and whites and blacks saw no benefit of any effort to learn about the “other America” down the block, across the bridge and beyond your bus stop.

Fast forward to 2019: Only 26 school districts out of 36,000 in the United States teach African-American history and culture as a non-elective course. (This writer used to work for the Core Knowledge Foundation of Charlottesville, Va., experts in multicultural education founded by Professor E. Don Hirsch Sr., formerly of the University of Virginia’s (UVA) Curry School of Education where this writer was an associate dean of the Office of Afro-American Affairs (0AAA) in 1987). Unfortunately, the landscape has not changed much since the riots following the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., as the same conditions that prompted those riots in the 1960s still exist today in every Northern and Southern urban area in this country. In every indicia of life in America, blacks, Native Americans and Latino Americans are still concentrated at the bottom According to The Wall Street Journal(July 2019), the wealth gap between blacks and whites is still growing despite 12 years of unprecedented economic growth that started in President Obama’s second term in office. White America is still fighting “integration” at the curriculum level by opposing any changes, additions or modifications of the basic Euro-centric teaching model of our educational system. This intransigent and antiquated teaching model which began in the early 1800s deprives “all people of color” of human dignity and equal cultural consideration.

The riots will continue until we learn from and acknowledge the mistakes of our past and confront our national prejudices based upon skin color, race, sex, religion and sexual persuasion. There is no other way to accommodate racism, as President Trump has in his refusal to condemn white nationalism and white supremacy, and then speak of a “united America!” This country shall never be united unless the evils of racism, sexism, homo-phobism, xeno-phobism and all other “-isms” be eradicated from the American landscape. In other words, no vestige of that “ugly America” can remain in this country, whether it is statutes, flags, civic and social groups, books, parades, festivals, hate films and music or any other form of prejudicial and discriminatory expression.

Professor Isenberg, I applaud your efforts to “clarify” one riot after another. I pray that others join your campaign, as that day that the black lambs can lay down with the white lions in harmony is still a distant hope of our future!