How Princetonians Saved ‘The Great Gatsby’

Released 100 years ago, F. Scott Fitzgerald 1917’s defining work was all but forgotten until these alumni helped transform it into an American classic

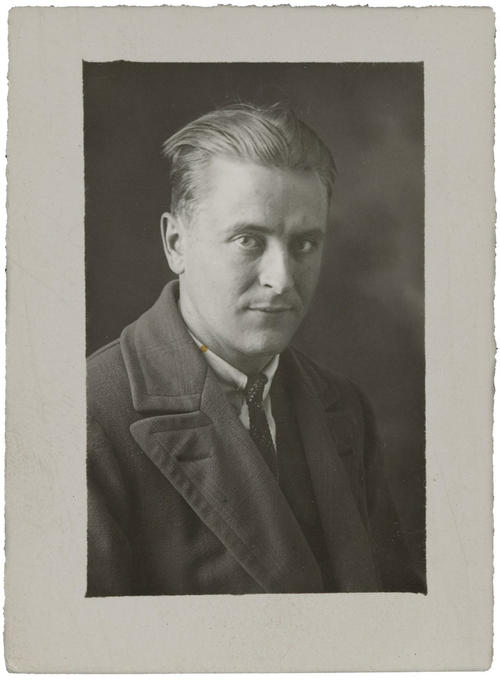

At the start of the 1940s, F. Scott Fitzgerald 1917 was, as the kids say, in his flop era. In the first year of that decade, the total sales for all of Fitzgerald’s books, from This Side of Paradise to The Great Gatsby, were a whopping 72 copies. The amount of scholarly ink spilled on him could fit into a thimble. When Fitzgerald died in December 1940 — of a heart attack, at the age of 44 — the world’s verdict on the author was that he was a tragic figure: a sort of literary sparkler who burned too bright, too young, then fizzled out when his decade did, enjoying great celebrity during the Jazz Age and losing it all in the 1930s when the public had too many worries to care about flappers and champagne.

His early death was all the crueler, critics said, because it came late enough for him to see the collapse of his youthful promise. On his 40th birthday, the New York Post published a profile that depicted him as a washed-up alcoholic who knew his best days were behind him, interesting only as a symbol of the failures of his generation:

Then the reporter asked him how he felt now about the jazz-mad, gin-mad generation whose feverish doings he chronicled in This Side of Paradise. How had they done? How did they stand up in the world?

“Why should I bother myself about them?” he asked. “Haven’t I enough worries of my own? You know as well as I do what has happened to them. Some became brokers and threw themselves out of windows. Others became bankers and shot themselves. Still others became newspaper reporters. And a few became successful authors.”

His face twitched.

“Successful authors!” he cried. “Oh, my God, successful authors!”

He stumbled over to the highboy and poured himself another drink.

If it were up to the world, perhaps that would still be his legacy: an obscure figure whose works scholars cite on rare occasions, but not someone whom readers or critics care about. Most books, as an eminent librarian once said, have rarely been read. But the pantheon of artistic greatness isn’t up to the world only. From time to time, Princeton intervenes to correct the world’s mistakes.

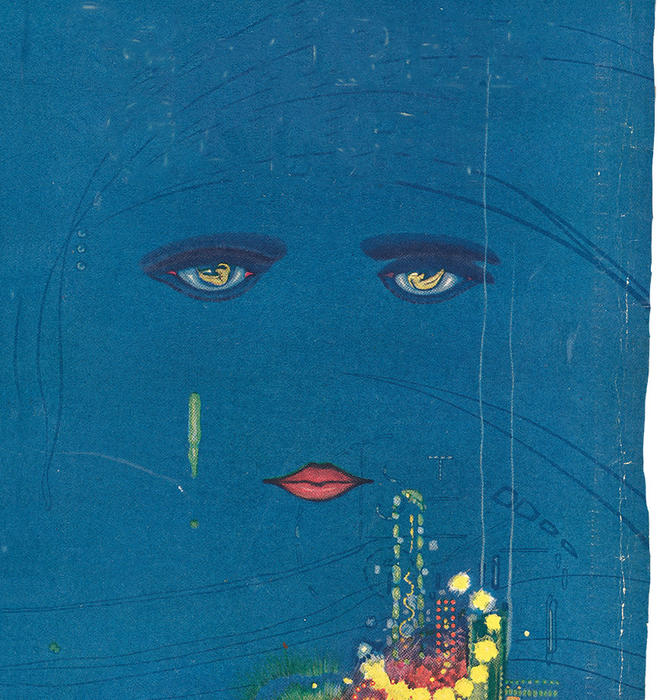

This year is the 100th anniversary of the publication of The Great Gatsby. Though today Fitzgerald’s novel is covered in honors — a perennial on lists of the greatest American novels, a staple in the classroom, the subject of movies and Broadway musicals — it owes its place in the canon to a valiant company of students, professors, and alumni from his alma mater. Though he was, for a time, forgotten, Princetonians recognized Fitzgerald as their poet laureate and kept his fire burning long enough for the world to recognize the lasting value of his work.

As artists even better than him have done — Mozart is an example — Fitzgerald died in penury. He was living in a girlfriend’s apartment in Los Angeles, drinking too much and scratching up a bare living by writing screenplays. At the time of his fatal heart attack, he was reading an issue of the Princeton Alumni Weekly.

Just 30 people came to his funeral. The newspapers covered his death, but the story they told was a tragedy of youthful talent squandered: “Roughly, his own career began and ended with the Nineteen Twenties,” said The New York Times. “The promise of his brilliant career was never fulfilled.” “Poor Scott,” Ernest Hemingway said of him, and the label stuck. Poor Scott, who died in the worst way an artist can die: too early, but late enough to see himself forgotten.

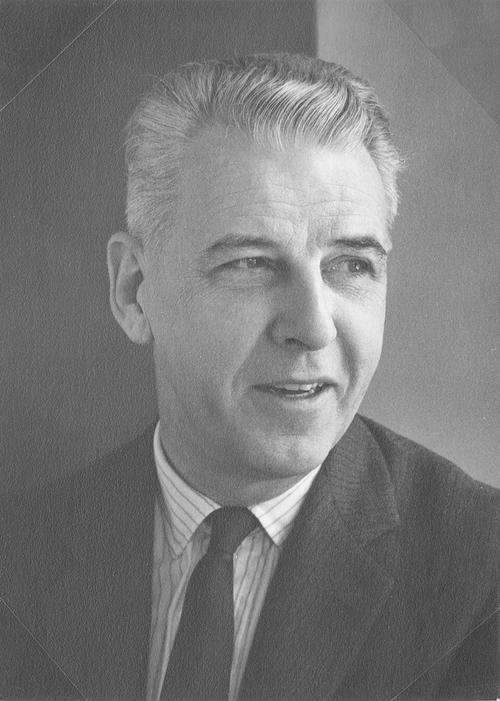

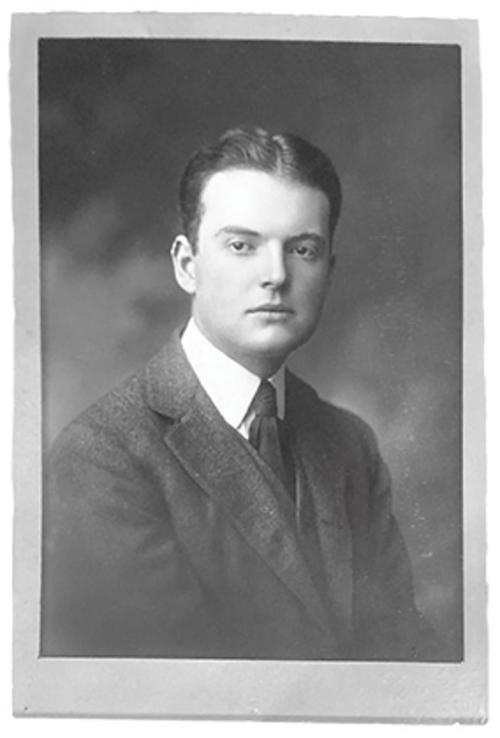

Three years after Fitzgerald’s death, a junior scholar named Arthur Mizener ’30 *34 — who had taken a Ph.D. in English literature at Princeton but hadn’t yet landed a permanent faculty job — was working as a dogsbody in Princeton’s library when it received Fitzgerald’s papers on loan from his estate. He took on the job of organizing them.

In the process, Mizener became so enamored with the author that he resolved to become his champion, as the literary historian William Anderson Jr. wrote in a 1974 study of Fitzgerald’s reception. Until then, Mizener had focused on early modern literature; his dissertation had been on 17th-century poetry. No more. He started publishing article after article about Fitzgerald, arguing that he deserved a place in the great American Romantic tradition.

“There is in Fitzgerald’s mature work,” he wrote, “a Proustian minuteness of recollection of the feelings and attitudes which made up the experience as it was lived; and there is, finally, cast over both the historically apprehended event and the personal recollection embedded in it, a glow of pathos, the pathos of the irretrievableness of a part of oneself.”

In 1951, Mizener published the first biography of the author, The Far Side of Paradise.

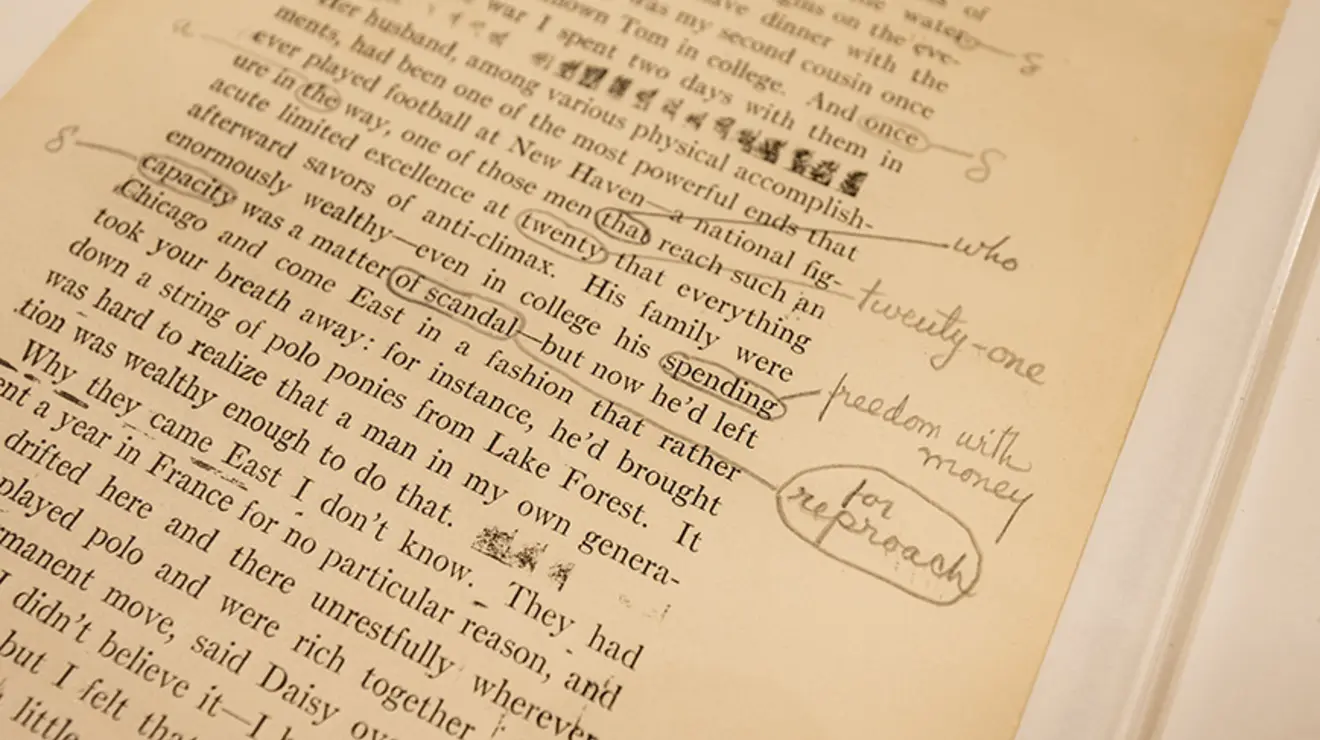

The papers were in the library in the first place due to the machinations of Willard Thorp *1926, a professor in Princeton’s English department. Thorp, who joined the faculty in 1926, thought the late author’s papers were an overlooked treasure. The only other person who believed they were worth anything might have been Fitzgerald himself, who, as one scholar commented drily, scrupulously preserved all his drafts, proofs, and correspondence “at a time when no one would have placed a wager on his chances for immortality.”

When Fitzgerald died, his estate was scarcely enough to merit the title: some insurance money, a little cash, and a set of literary copyrights that appraisers deemed valueless. The estate’s executor, John Biggs 1918, Fitzgerald’s roommate at Princeton, had liked Fitzgerald as a person, but he shared the world’s assessment of him as a writer. He thought selling Fitzgerald’s papers would bring in at least a little scratch for his heirs, but Fitzgerald’s daughter resisted, writing, “If that library were worth $.50 or $10,000, I couldn’t bear to part with it.” Thorp, who knew that wars are won inch by inch, offered to house the papers at Princeton temporarily. She agreed.

In his memoir, David Randall, a rare book dealer who worked for Fitzgerald’s publisher, Charles Scribner’s Sons, said he wanted to make an offer for the papers, but was prevented by his bosses because they thought he was just being charitable to the surviving family. Princeton offered $1,000. (Not everyone at the University was a fan of Fitzgerald’s work; when Randall told a Princeton history professor that $1,000 was a lowball number, “I was reminded tartly that Princeton was not a charitable institution, nor was its library established to support indigent widows of, and I quote, ‘second-rate, Midwest hacks.’”)

In 1950 — after almost a decade of negotiations that Thorp insisted Princeton see through — Princeton would pay $2,500 to make its temporary custodianship of the papers permanent.

In the meanwhile, World War II was raging, and the U.S. government launched a curious wartime initiative that played an unexpected role in Fitzgerald’s literary comeback.

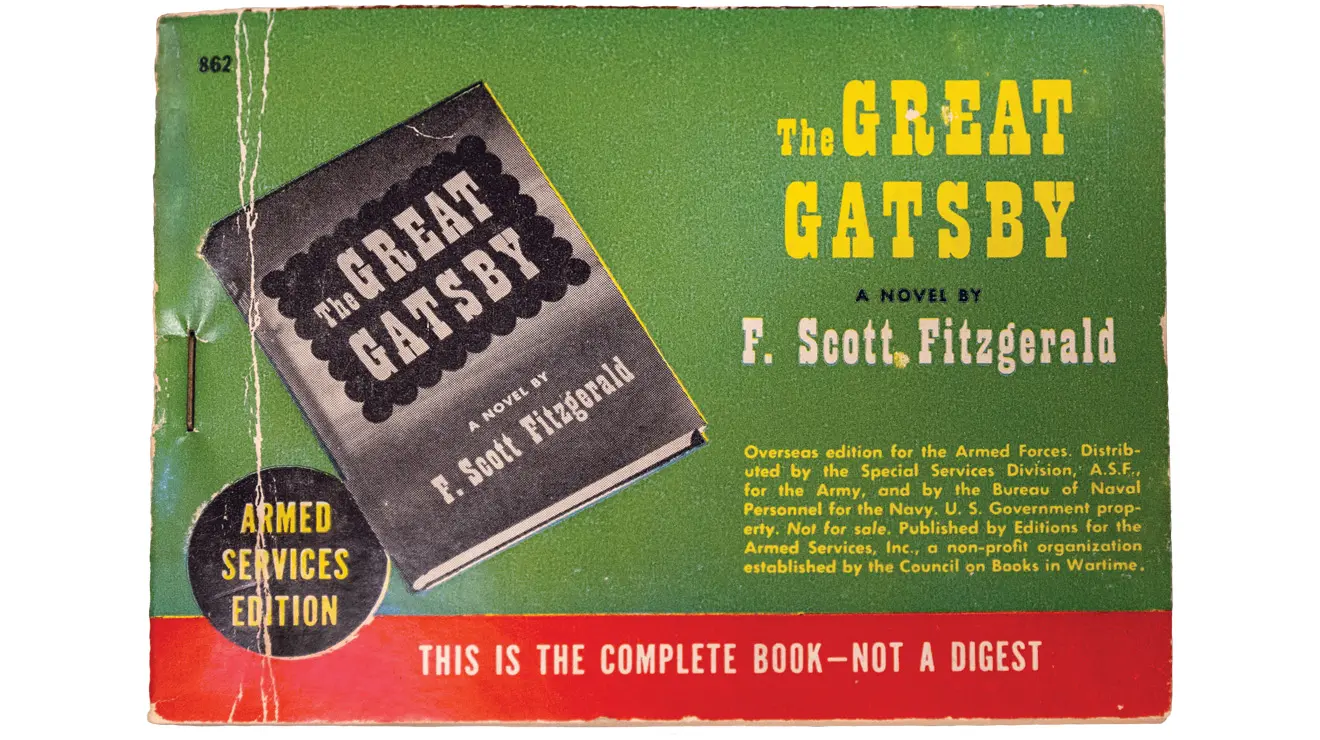

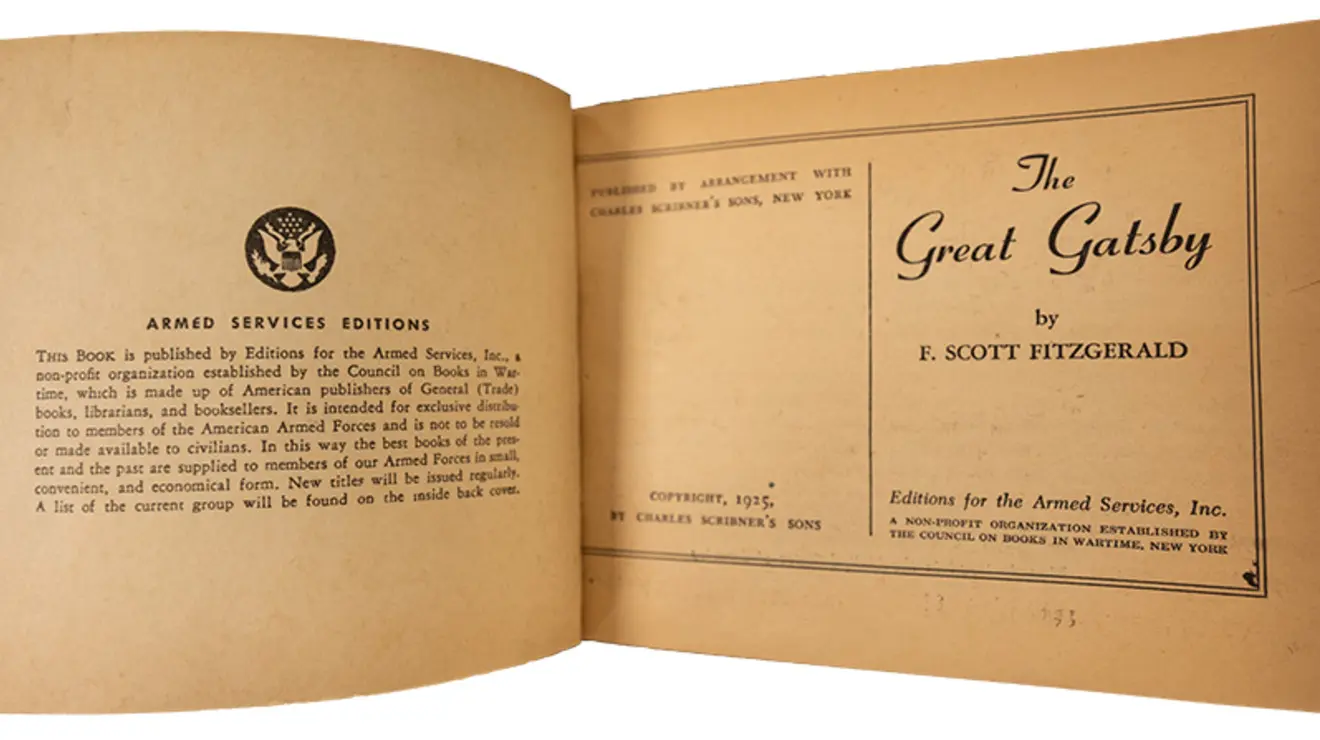

The military collaborated with the publishing industry to send free books to servicemen abroad, putting together a Council on Books in Wartime in 1942, with a board of directors assembled from top publishing executives, to choose the books that would be selected for this purpose. (The records of the Council on Books in Wartime are at the Princeton University Library.) Once chosen, the books were reprinted in a new format, the Armed Services Editions. Small enough to fit in a pocket, these books were printed on newsprint paper, which meant they were incredibly cheap to make.

The Council chose two of Fitzgerald’s books for this series: The Diamond as Big as the Ritz and Other Stories and The Great Gatsby. Why these books? Scholars have suggested different theories. Publishers were the ones who offered titles for the council to choose from, and perhaps Scribner’s offered up Fitzgerald’s works so it could do its wartime duty without giving up truly valuable titles. Perhaps the council was running out of bestselling fiction, or perhaps it thought the setting of Gatsby, a period of postwar prosperity to the point of excess, would hearten young men who were looking ahead to a new postwar period after the fighting.

Whatever the case, the Armed Services Edition of The Great Gatsby — a handsome little green affair, 222 pages long and weighing just 2.3 ounces — put the novel into the hands of some 155,000 readers. A capsule biography of Fitzgerald that follows the novel’s text calls Gatsby “his greatest novel” while rehearsing the story of his ruined promise: “F. Scott Fitzgerald gave a name to an age in American life, lived through the age, saw it burn itself to a grim cinder — and wrote finis to it. Few authors have such an achievement to their credit.”

After the war, authors whose books came out in the Armed Services Editions reported a bump in sales. (The humorist H. Allen Smith said he received more than 1,000 letters from readers who discovered his books in the trenches.) But more importantly, the Armed Services Editions proved to publishers that the paperback format worked. The postwar publishing industry saw a rush of new paperback imprints, and Scribner’s, still unsure of Gatsby’s value, leased the reprint rights to the novel to seemingly as many imprints as it could. By the end of 1946, Anderson notes, Gatsby was out in three commercial paperback editions.

A book can’t be rediscovered without readers. Without paperbacks, there is no Gatsby. The fate of literature is inextricable from the fate of books.

Yet plenty of books have come out in paperback without rising to the top of the canon. That kind of breakthrough relies on the labors of critics — and Princeton critics were on it.

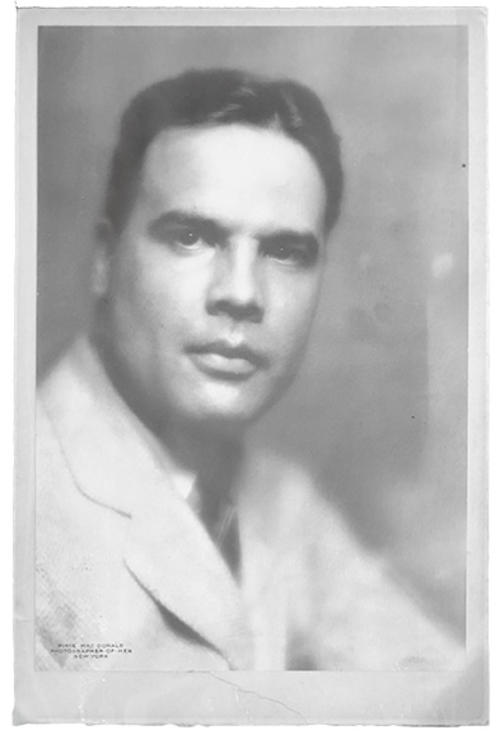

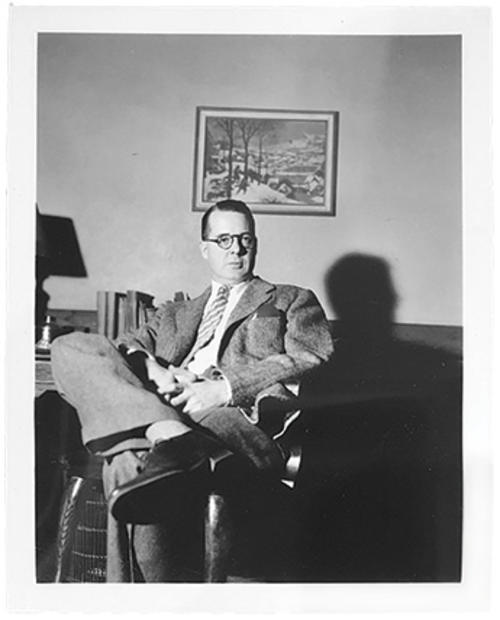

Edmund Wilson 1916 was a great champion of Fitzgerald’s work both during Fitzgerald’s lifetime and after. To be sure, the two had a complicated relationship, as always happens when authors admire each other enough to feel threatened by each other. When he gave Fitzgerald writing advice, Wilson was often brutal, and his generous work editing the younger man’s posthumous books, The Crack-Up and The Last Tycoon, happened “when Fitzgerald was no longer a rival and a threat,” as the Wilson biographer Jeffrey Meyers notes. Fitzgerald, in turn, knew what he was doing when he gave Jay Gatsby’s murderer the surname Wilson.

No matter. Throughout his career, Wilson — who, at Princeton, edited Fitzgerald’s work for the Nassau Lit and collaborated with him on a play for the Triangle Club — kept Fitzgerald’s name before the readers of Vanity Fair, The New Republic, and other magazines he wrote for as a critic. After Fitzgerald’s death, Wilson continued to give him the treatment due to an important author, preparing his final manuscripts for publication and publishing a poem in The New Yorker titled On Editing Scott Fitzgerald’s Papers. In the foreword to The Last Tycoon, Wilson gave Fitzgerald his strongest praise: “Fitzgerald will be found to stand out as one of the first-rate figures in the American writing of the period.”

John Peale Bishop 1917 also wrote, before his death in 1944, a number of essays in praise of Fitzgerald, two of which Wilson reprinted in a collection in 1948.

Mizener, meanwhile, was working up an industry in Fitzgerald studies. Mizener had finally gotten a faculty job at Carleton College. Working from his new post as a professor, Mizener published study after study of Fitzgerald’s work — sometimes fighting to persuade the editors of academic journals that the author was worth studying. Willard Thorp, the Princeton professor who pressed the University to acquire Fitzgerald’s papers and Mizener to sort them, also introduced Fitzgerald’s works to Henry Dan Piper ’39, who became another mighty Fitzgerald scholar and biographer. Thorp published a book about famous Princetonians that dedicated a chapter to Fitzgerald.

By the 1950s, all of this scholarly and critical activity was having an effect. Fitzgerald’s work was appearing in college readers, showing that faculty were demanding it from publishers, as well as mass-market paperbacks such as The Portable F. Scott Fitzgerald, which was in its fifth printing by 1951. Graduate students were writing theses on him by the score.

In 1956, a literature professor named Martin Shockley published an article in The Arizona Quarterly complaining that Fitzgerald had become too popular, and that Princetonians were falsely inflating his stock: “It is, I suggest, time to shush the Princeton locomotive, to sweep the wildly thrown bouquets into the wastebasket, and to say, ‘Sit down in front.’ When that is done, responsible literary scholars may, with dignity, place upon Fitzgerald’s brow the small and wilted laurel that is his.”

Little did he know that there is no shushing the Princeton locomotive. That same year, PAW published an issue dedicated to Fitzgerald, calling him “the greatest of Princeton authors, not only because of the distinction of his work but because he was the most Princetonian.” Even then, his reputation was unsettled enough for the issue to set off a debate that earned coverage in The New York Times — which argued that college campuses, in particular, were seeing a growing fascination with Fitzgerald because his tragic outlook resonated with the young people then in college: the Silent Generation, which was skeptical of grand narratives and “doesn’t care to say the silly and dishonest things that are expected of it.”

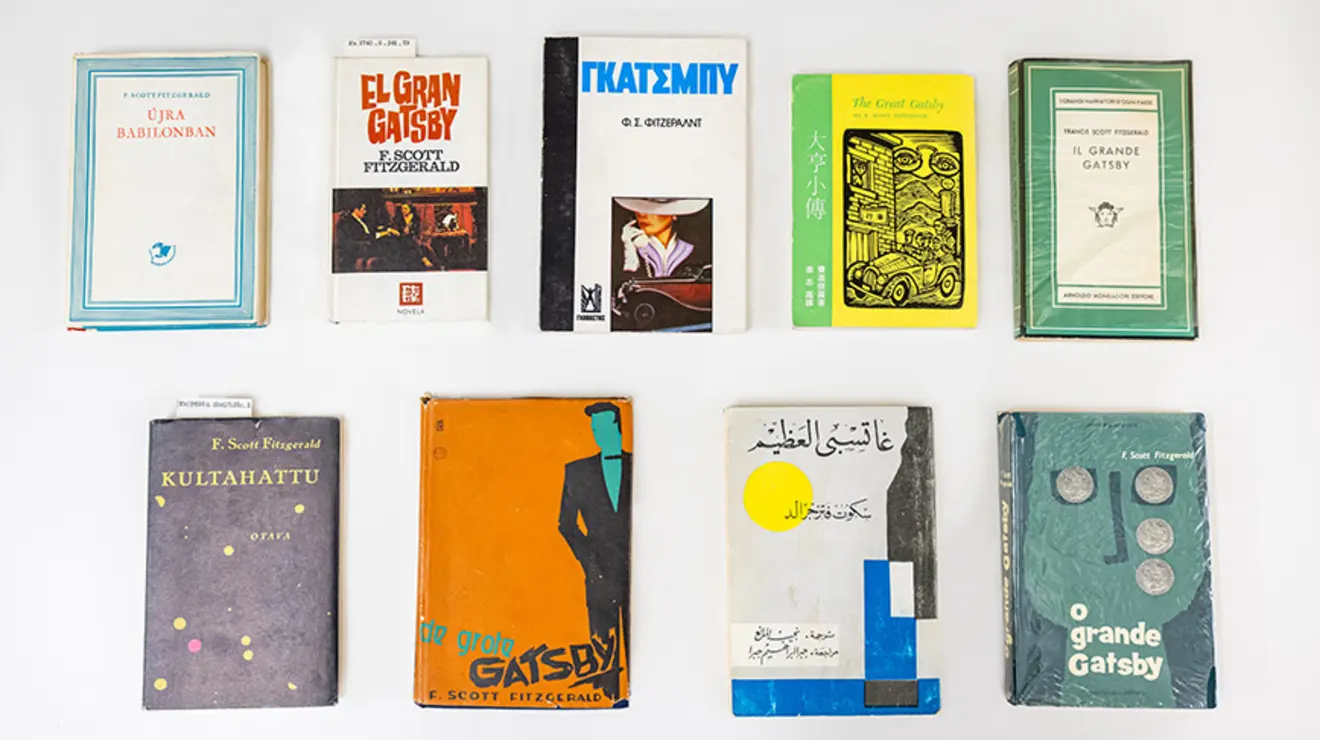

By 1974, as Anderson notes, Fitzgerald’s works had been “published in at least 172 editions in foreign languages, including a pirated El Gran Gatsby, published in communist Cuba.”

It’s true that the book’s new readers often read The Great Gatsby as young people do: by projecting its meanings onto their own lives, and vice versa. In J.D. Salinger’s novel The Catcher in the Rye, an instant classic of the 1950s, Holden Caulfield says he’s “crazy about” Gatsby, seeming to feel a connection with the tragic title character: “Old Gatsby. Old sport. That killed me.” Popular culture capitalized on the impulse to identify with the characters. Young people threw “Gatsby parties.” Gentleman’s clothiers offered, along with silk shirts and double-breasted suits, “Great Gatsby bow ties.”

All of this would be impossible, of course, without Fitzgerald’s publisher, Charles Scribner’s Sons. The Scribners are a Princeton family: Charles Scribner 1840, John Blair Scribner 1872, Charles Scribner II 1875, Arthur Scribner 1881, Charles Scribner 1913, Charles Scribner Jr. ’43, Charles Scribner III ’73 *77, Charles Scribner IV ’05, Elizabeth (Yates) Scribner ’06.

Scribner’s was present at every step in Fitzgerald’s revival: offering Gatsby to the Armed Services Editions, leasing it to lots of paperback imprints after the war, bringing it out in mass market and college and high school editions as the novel grew ever more popular in the second half of the century. The publisher surely didn’t foresee Fitzgerald’s great reversal of fortune, but it kept him in print and gave him nudges along the way, and the investment paid off magnificently. By 1961, when Scribner’s was once again publishing Gatsby under its own imprint, the novel “was selling 13,000 copies per month,” Anderson notes.

Inevitably, that kind of success meant readers forgot there was ever an American literature without Gatsby. A great work of art feels timeless: like it always existed; like it was always known. By 1974, when Paramount Pictures was making a film version of Gatsby with the biggest stars in Hollywood, Robert Redford and Mia Farrow, everyone involved in the picture — as well as the reporters covering the star-studded production — could, and did, assume that Gatsby had always been a classic. One reporter asked a crew member, “Does the film have a happy ending?”

“Have you read the book?” the crew member asked, astonished.

“Of course. Several times.”

“Then you know Gatsby is killed?”

“Certainly. But it’s a Hollywood movie. Don’t they always change things to make a happy ending?”

Why did Princetonians love Fitzgerald so much? Perhaps because his collected works, Gatsby included, can be read as a long love letter to Princeton. In 1942, his daughter, Frances Scott (called Scottie), told the Nassau Lit, “My father belonged all his life to Princeton. Any graduate was welcome at the house; any undergraduate was questioned in great detail. He followed the athletics, the club elections, the Princetonian editorials … . I believe that Princeton played a bigger part in his life as an author and as a man than any other single factor.”

If Fitzgerald was the bard of almost making it in America, Princeton was where he almost made it: where he made well-heeled friends, joined the local literary lions, wrote the draft of his first novel — and then, ignominiously, had to drop out in his senior year.

“Princeton was to have a lasting hold on him as the place where he had almost won but hadn’t,” his biographer, Mizener, told a reporter from The Princeton Herald. The reporter expanded on the idea: “The boy who came from St. Paul to college was acutely self-conscious and naive in many ways and Princeton represented to him everything he wanted to be and to master. Because for one reason or another he did not entirely succeed, Princeton became a symbol to him of his failure and he remembered it bitterly.” (Should it be the orange light at the end of the dock?)

And yet, Fitzgerald’s ultimate triumph, his place today atop the American literary canon, came about because his alma mater remembered him. Princeton’s Class of 1917 sent flowers to his funeral. And his fellow Princetonians championed his stories — even and especially his stories of failure. His themes and characters are often spoken of, today, as innately American: the optimism tinctured with anticipatory regret; the sense of youth’s possibilities and its brevity; the sense of being charmed and glamoured by an aristocratic beauty and elegance that requires, ah yes, a fatal compromise; the “spoiled priest,” as Fitzgerald described one of his narrators, who holds an idealistic distance from a world of money and carelessness that he also longs to join.

Fitzgerald stood before the promises of American life like a schoolboy, to borrow a phrase, with his face and nose pressed to a sweet-shop window. But if we were to look more closely through that window, who’s to say we wouldn’t see the dreaming quads of Princeton?

Elyse Graham ’07 is an English professor at Stony Brook University.

10 Responses

Kent Hughes ’67

2 Weeks AgoRemembering Professor Thorpe

I have fond memories of Professor Thorpe, who taught me (at least once) when I was a Princeton student.

Patrick Bernuth ’62

8 Months AgoHenry Reath ’69 and the First Edition Library

I was dismayed to note that in an article of several thousand words on “How Princetonians Saved The Great Gatsby” there is no mention of Henry Reath ’69 and the First Edition Library (FEL). Founded by Henry, his wife Mary Reath, and Kemp Battle, FEL published carefully researched replica editions of American literary classics. The first three FEL titles produced were For Whom the Bell Tolls, Of Mice and Men and, yes, The Great Gatsby.

The FEL editions duplicated the originals as closely as possible: same weight, size, typeface, art, dust jacket, finish, and texture as the originals. FEL hired engravers to reproduce typefaces that were no longer used. The sewn bindings, stamping, and even the original price on the jacket flap were all exact replicas.

Each publication contained a laid-in card of explanatory notes, including how the title came into being, background on the dedication, the target copy from which the facsimile was produced, and some general notes about the book and its readership. In the case of Gatsby, the target copy came from Firestone Library. Most of the research that went into producing the FEL edition of Gatsby came from Firestone Library.

Surely the Reaths and the First Edition Library made a noteworthy contribution to “How Princetonians Saved The Great Gatsby.”

Paul A. Hager ’64

9 Months AgoMind Your Predicate Nominatives

Although not an English major, I enjoyed almost all of the piece on “How Princetonians Saved The Great Gatsby,” in the last PAW. I say almost all because as someone who took several years of Latin while it was still taught in our public schools and was forced to diagram sentences seemingly ad nauseam in junior high English class, it was disheartening to read on the first page the following topic sentence: “As artists even better than him have done ... Fitzgerald died in penury.” As a lifelong educator, primarily at the secondary level, and daily reader of publications such as The New York Times, I have come to realize that the teaching of traditional/formal English grammar is a thing of the past. That said, it is still jarring to read or listen to misuses of the predicate nominative by educated writers/speakers. If the author did not realize her mistake, an editor should have.

Jerome P. Coleman ’70

9 Months AgoCottage Club Library’s Tribute to Fitzgerald

Kudos to Elyse Graham ’07 for her illuminating and well-crafted piece on the resurrection of Fitzgerald by various Princetonians.

As a high schooler I was intrigued by John McPhee ’53’s portrait of Bill Bradley, A Sense of Where You Are, as well as Scott’s This Side of Paradise.

While writing my thesis in the Cottage library a few years later, it was greatly ironic to view Bradley’s mention in the display of Rhodes Scholars, and Scott’s original transcript pages under glass within feet thereof.

After consult with the director of the Rare Book Room in Firestone (where I also toiled), and the consent of the UCC Grad Board, the originals are now in Firestone and photostats are replicated in the library of his beloved club.

Lew Hitzrot ’64

9 Months AgoGrowing up in the Fitzgeralds’ Connecticut Home

Elyse Graham’s article “How Princetonians Saved The Great Gatsby” was of particular interest to me. I had recently viewed the documentary Gatsby in Connecticut: The Untold Story, and I grew up in the house on South Compo Road in Westport, Connecticut, where Scott and Zelda summered in 1920. The house is situated on property bordering a golf course whose clubhouse is an imposing turn-of-the-century building with a lawn stretching down to Long Island Sound. From the house I lived in, it’s a short walk across the fairways to that clubhouse. In the ’20s the clubhouse and the 175 acres that eventually became the golf course were the home and estate of tycoon Frederick E. Lewis. The documentary includes a number of pictures showing Scott and Zelda at parties on the grounds of the Lewis property and it makes a compelling case that the estate, its flamboyant owner, and the extravagant parties that occurred there were the inspiration for The Great Gatsby, even pointing out that, from the beach in front of the clubhouse, one can view green lights on the far shore.

I’ve often speculated about the wild parties that must have taken place in our house during the Fitzgeralds’ occupancy. For me, growing up in the ’40s and ’50s, it was a safe, comfortable home. Perhaps it was just recuperating after the tumultuous events of the summer of 1920.

Gary Forlini

9 Months AgoAnother Alumni Biographer of Note

One more Princetonian biographer of Fitzgerald, Andrew Turnbull ’42, well understood “the pathos of the irretrievableness of oneself” identified in the article by Arthur Mizener ’30 *34.

At 10 years of age, Andy met the Fitzgeralds when they rented a house on the Turnbulls’ property in Maryland and so began an association between them, largely by mail after the Fitzgeralds moved on. Andy’s choice of Princeton enjoyed a personal element.

Following graduation, Andy’s World War II service was aboard the USS Palmer along with Chief Engineer James “Smokey” Stack ’43. The ship was sunk in January 1945 by a lone Japanese aircraft. Andy survived the event; Jim did not.

Fitzgerald remained integral to Andy’s “Proustian minuteness of reflection of … feelings and attitudes” (Mizener), and so he began to publish articles about the author in the 1950s and then a Fitzgerald biography described as “remarkably straightforward and suspenseful” by the New York Times Book Review in 1962, followed in 1963 by his volume of collected letters arranged to shed light on Fitzgerald’s personal life.

Upon the 25th anniversary of the sinking of the Palmer, Andy took his life.

David Perlsweig ’77

10 Months AgoGreen Light, Orange Light

Professor Graham asks: “Should it be the orange light at the end of the dock?”

The answer: It very nearly was.

Start with lime green (top), shift the RBG color values one (byte) step to the left, and the result is Princeton orange (bottom).

Isn’t it fitting that the green light at the end of the dock was just one step away from Princeton orange?

If only it had truly been lime green to begin with.

(Note: Other variations of Princeton orange will yield similar results; for example, https://www.colorhexa.com/f58025 vs. https://www.colorhexa.com/25f580.)

Scott Kendall ’97

10 Months AgoBelated Appreciation of Gatsby as a Classic

Great article. Having had Gatsby assigned three times in my school career, had assumed it’d been an instant classic. The backstory is surprising. The posthumous appreciation of Scott’s works is a gut-punch. A reminder that it’s the journey, not the appreciation, that really matters.

Peter Kloehn

10 Months AgoFitzgerald Fan

Fitzgerald is my favorite writer!

I’ve read and studied almost everything about him and by him. He is so much more than Princeton. He’s so much part of his life’s love, Zelda — also a great writer. Gatsby is without a doubt the “great American novel” of the 20th century (Twain’s Huckleberry Finn of the 19th century).

Every element of 1920s America simply and beautifully points to Gatsby. To use a now outmoded characterization, it is a genuine Masterpiece. And F. Scott Fitzgerald remains one of our most elegant and gifted stylists to ever apply pen to paper. Oh had he lived to finish Last Tycoon and go on to write more …

William Elkins ’54

10 Months AgoLatecomer to Gatsby

1n 1953 or ’54, I took Professor Thorpe’s course on American lit. Gatsby was not assigned or discussed, and I didn’t read it until last year. Ho-hum! I’m more interested in Dick Kazmaier, Ernest Hemingway, and President Shirley Tilghman.