IDEAS: Using burgernomics to measure wages

Since Roman times, economists have struggled with the difficulty of measuring the “real-wage rate” across nations: How much product can a given period of work buy? Such a measure could provide a valuable index of the standard of living of workers but is plagued by pitfalls.

Suppose one asks, “How many wagons can a wagon-maker buy with a year’s salary?” Alas, wagons don’t look the same in Estonia, Egypt, or El Salvador and require very different skills to construct. Wagons provide a flawed measure.

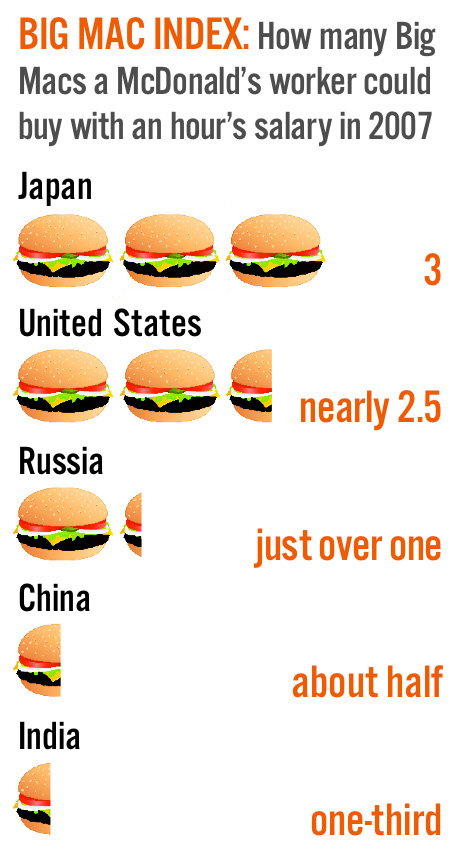

To this age-old problem, economics professor Orley Ashenfelter *70 has found a solution: a product that is basically the same everywhere — the McDonald’s Big Mac. Since the late 1990s, Ashenfelter has compiled what he calls the Big Mac Index, which cleverly gauges the real-wage rate in more than 60 countries. (A separate Big Mac Index, by The Economist, calculates the value of international currencies.)

To plug a nation into his Big Mac Index, Ashenfelter requires just two pieces of information: How much does a Big Mac cost locally? And how much does McDonald’s pay its crew there? The Big Mac Index demonstrates that workers are paid vastly different amounts to perform the same tasks, depending on the country.

Not only is the Big Mac standardized, but “workers are doing the exact same thing” when they make one, Ashenfelter says. If they are paid less to make one in the Third World, it’s not because the work is easier or the workers less competent. Developing countries’ economies are less productive, which pushes down prevailing wages. McDonald’s workers may be just as productive in India as in, say, the United States, but they are paid the going wage rate, which is less in India.

Before the Industrial Revolution, real-wage rates were the same everywhere, barely above subsistence level, Ashenfelter says. Ever since, rates have varied, employers being forced by competition to pay workers more in developed countries.

The index shows huge growth in real-wage rates in India, Russia, and China since Ashenfelter began measuring there in the late 1990s. But since the recession, “it’s kind of a sad story,” he says. Among emerging economies, “The least democratic countries are the ones doing the best — Russia and China. India is starting to backslide.”

1 Response

Bob Hills ’67

10 Years AgoBig Macs and pricing

As an executive at a leading pharmaceutical firm in the 1980s, one of the great challenges was establishing a fair and transparent pricing system for lifesaving drugs marketed worldwide. Beyond our own strong sense of ethical pricing behavior, we were subject to strict price controls in many countries, oversight in congressional hearings, various patent regimes and threats, shareholder expectations, and media commentary, among many other considerations. At one point a worldwide “single price” subject only to fluctuations in currency exchange rates was the gold standard (for developing countries in Africa, free product through NGOs was a safety valve, and for, say, China and India, widespread ignoring of patents served the same though not lightly tolerated end).

Reading about the simple elegance of the Big Mac Index (Campus Notebook, Oct. 10) gave me hope that better approaches might be developed to deal with the perplexing problem of bringing first-rate technology at “objectively” fair prices to most of the peoples of the world, even within the flawed constraints of market capitalism. I say this, however, not to exclude more straightforward “non-market” (but public and private R&D-supportive) solutions, which many readers might suggest.