As Americans debate the place of immigrants in our society, the University has spoken strongly in favor of their presence. In the words of President Eisgruber ’83, “Throughout its history, the United States has benefited from the abilities, creativity, and drive of immigrants from throughout the world.”

But in the 1840s, when nativism entered the country’s lexicon, Princeton was less welcoming. An unprecedented influx of Irish and German immigrants was changing the religious composition of many communities, inflaming long-standing anti-Catholic prejudices. Princeton president James Carnahan 1800 had endorsed a publication called The Protestant, created in part to respond to “the astonishing and fearful increase of Popery in the United States.” And in July 1843, The Nassau Monthly published the first installment of a two-part article, titled “American Citizenship,” that exemplified this animus. Its unnamed author was later identified as John Joseph Entwisle, the Class of 1843’s Latin salutatorian.

Contending that the “indiscriminate bestowment of the rights of citizenship on immigrant foreigners” is “pernicious to our institutions and destructive of our welfare,” he argued that the depth of newcomers’ ignorance surpassed even that of enslaved Americans, who themselves could hardly be thought “capable of judging and deciding on our questions of policy, even the most simple.”

For Entwisle, it was Catholicism that placed most immigrants beyond the pale. “Every year,” he noted, “at least one hundred thousand Catholic immigrants come into our country” — adherents of a “religio-political system” that is “the most totally destructive of every thing dearest to man in this life and the next.” Abandoning all restraint, he continued: “The rights of American citizenship were obtained only with the life’s blood of men who had more of noble principle ... in a little finger, than is contained in a whole cargo of the cast-off refuse of Europe that inundate our shores. And shall these by their vile breath pollute, and their viler touch destroy what those paid such a price to obtain?”

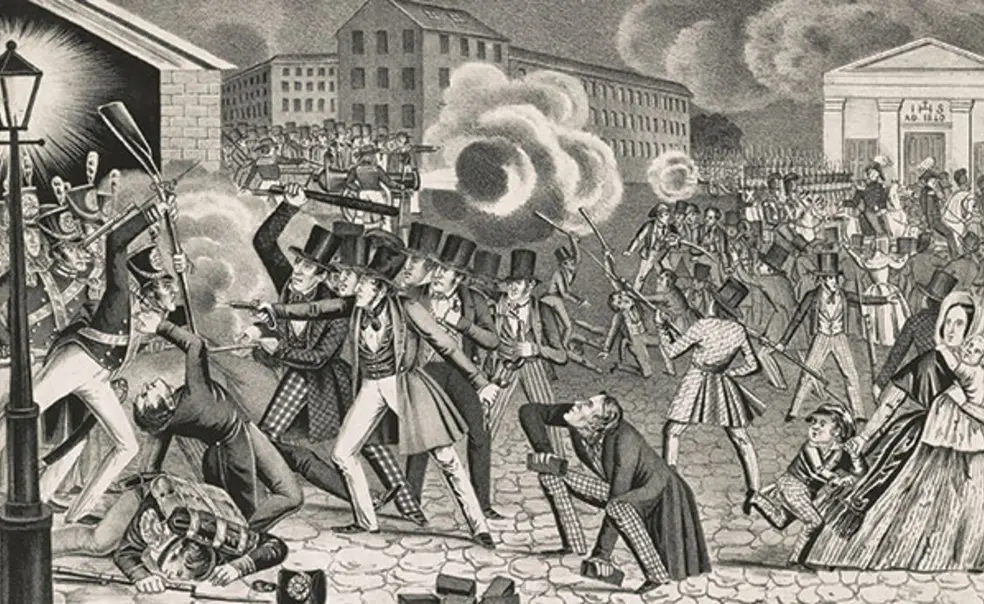

The following year, in Philadelphia, nativist mobs answered this question by running amok in Catholic neighborhoods, leaving a trail of death and destruction that even the state militia was hard-pressed to contain.

John S. Weeren is founding director of Princeton Writes and a former assistant University archivist.

2 Responses

Tim Entwisle

2 Years AgoWho Was John Joseph Entwisle?

I am a distant relation of John Joseph Entwisle. It is worth noting the context of his anti-Catholic views. He came from a very strong and highly active non-conformist family from the north of England. His great uncle was John Pawson, a Wesleyan Methodist Minister and leading light of the church. “A man of deep but simple piety, he is remembered for having in 1796 burnt many of Wesley’s papers and his annotated copy of Shakespeare, which he considered ‘unedifying’.” [i.e. a bit overzealous]. Pawson’s niece, JJE’s grandmother, Mary Pawson, married the Rev. Joseph Entwisle (his grandfather and my forebear), who was a Wesleyan Itinerant and Governor of the Hoxton Theological Institution in London. Rev. Entwisle had been converted by Wesley himself. Hoxton College trained young Wesleyan ministers, many of whom became missionaries in the South Pacific. JJE’s father and three uncles were Protestant ministers (Itinerants). One of his cousins married a famous missionary to Tonga and New Zealand (where there was no love lost with the Catholic missionaries who spend no time educating the people they were converting).

JJE’s father died when he was a young boy (he had died after tending to a sick neighbor with yellow fever and contracting the disease himself). JJE was placed under the care of his pastor, the Rev. Dr. Breckenridge, a Presbyterian minister of Baltimore (who became Principal of Jefferson College, Canonsburg, Pennsylvania), who said, “I knew this youth perfectly, for about twelve years; indeed he was almost as a son in my house, and was very dear to us all. And I can truly say, I never knew a human being who gave more complete evidences of being born of God.” … “This promising young man died on the 8th of June, 1846, in the 23rd year of his age.”

I hope you will not judge him too harshly, as he was a child of his family, one that sacrificed much to their Protestant duty (and which had no love of the Catholic church). And we are proud to know that he was a graduate of Princeton so long ago (joining contemporary relatives that have been graduates of London, Sydney, and other world-class universities).

Norman Ravitch *62

7 Years AgoAs American As Apple Pie

As it turned out Catholicism in America, suspected from the start of the nation by the Protestants who left Britain because of alleged Catholic tendencies in the Church of England and by Protestants generally, did not finally pose any challenge to American values. Indeed, Catholics became along with other religions as American as apple pie. But why?

In Europe and in Spanish America Catholicism was anti-liberal, intolerant, united with all sorts of reactionary policies, some of which lasted into the mid-20th century. But the Catholic immigrants did not bring this sort of Catholicism with them, nor did most of their priests. Irish and Austrian and French and Eastern European Catholicism never arrived here with its adherents. In fact, at one point in the late 19th century the Vatican condemned what it called "Americanism," a view of religious liberty and separation of church and state not found in historic Catholic nations and not appreciated by the Roman authorities. While "Americanism" as a fictitious heretical doctrine was condemned American immigrant Catholics continued essentially to practice a form of Catholicism never found since the conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity: a religion of freedom, free thought, and individual liberty.

I think the reason was that the Catholic immigrants approved of American religious freedom and pluralism, something they had never experienced in their homelands, and that they realized despite anti-Catholic prejudices that they encountered owing to the old church-state semi -feudal Catholicism of their homelands was not what made them loyal to the church. They were Catholics in spite of the oppressive history of their church not because of it. Those traditionalist Catholics did not disappear in America, but they were quickly marginalized and by the election of John F. Kennedy no longer in favor. America has gained, Catholics have gained, and the much embattled Roman Church has, despite its denials and obfuscations, gained as well. Freedom is always good -- even for religion and religious people.