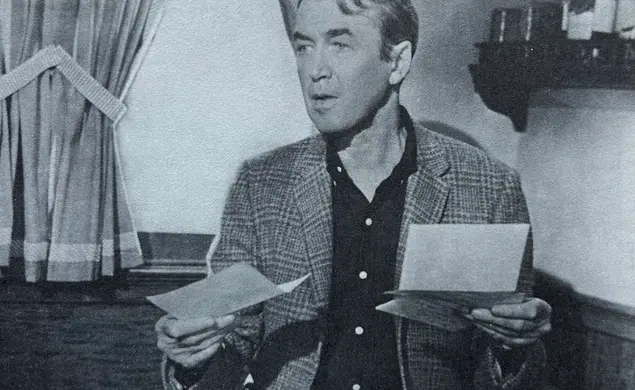

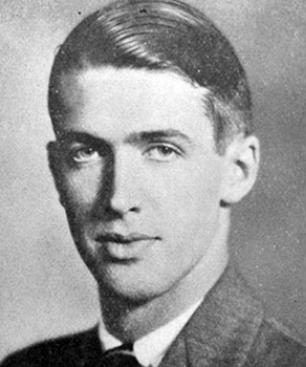

The Importance of James Stewart ’32, Actor

Now that James Stewart ’32 has signed on with prime-time television, the alarming possibility looms that his exceptional career in the movies will be washed out of sharp focus by countless TV segments. In his article, film critic Andrew Sarris looks back over Stewart’s long film career and makes a number of astute judgments on his importance to the medium. Jimmy Stewart began acting at Princeton in the famous Triangle Club that included José Ferrer ’33 and Joshua Logan ’31. He is the son of Alexander Stewart ’98 and served as an alumni trustee-at-large from 1959 to 1963. He hoped to study architecture after leaving Princeton, but later decided to give it up— much to the pleasure of anyone who enjoys the movies.

Andrew Sarris writes a weekly column of film criticism for The Village Voice and is the author of many books, including The American Cinema, The Film, and The Films of Josef von Sternberg.

I have been commissioned to write a piece about James Stewart on the basis of a cryptic remark which appears in a book of mine entitled The American Cinema: “The eight films [Anthony] Mann made with James Stewart are especially interesting today for their insights into the uneasy relationships between men and women in a world of violence and action. Stewart, the most complete actor-personality in the American cinema, is particularly gifted in expressing the emotional ambivalence of the action hero.”

“The most complete actor-personality in the American cinema”? Now what could I have possibly meant by that? Perhaps simply that Stewart has incarnated and articulated a uniquely American presence on the screen throughout his long career, and a presence moreover that is more complex than it seems at first glance. I would add that Stewart is primarily a screen actor and a Hollywood screen actor at that. His few forays on the stage have not been of such a quality as to challenge the Gielguds, the Oliviers, the Richardsons, the Redgraves and the Scofields.

Still, he is their better on the screen where behavioral consistency in a world of objects and vistas is more important than the vocal realization of a character from a printed page. This judgement would probably cause more gnashing of teeth in New York with its long tradition of mindless Anglophilia in the theater than in London with its perverse appreciation of American vitality and physicality.

Indeed, I recently had a quarrel with the British editors of a reference work I was preparing, they arguing that Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas were more crucial entries than Laurence Olivier and Ralph Richardson, and I arguing the opposite. Actually, my first intimations of Stewart’s having been grossly underrated came in Paris in 1961 at screenings of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much and John Ford’s Two Rode Together. Two sequences stand out in my mind, and in both there is an unforgettable image of Stewart’s long legs awkwardly stretched out as a metaphorical confirmation of his quizzical countenance. The excessively cerebral French, of course, know a good physical thing when they see it, and François Truffaut has acknowledged the influence of the river bank sequence in Two Rode Together in which Stewart sits and talks with Richard Widmark on a similar Truffaut sequence in Jules and Jim.

However, Stewart’s lanky physicality was not so much a key as a clue to the deeper meanings of his acting personality. To get to these deeper meanings requires an examination of the artistic contexts in which he has functioned most effectively. After all, feelings on the screen are expressed not so much by actors as through them. Hence, we can’t really trace Stewart’s contribution without dragging in such directors as George Stevens (Vivacious Lady), Frank Capra (You Can’t Take it With You, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and It’s a Wonderful Life), Ernst Lubitsch (The Shop Around the Corner), Frank Borzage (The Mortal Storm), George Cukor (The Philadelphia Story), Alfred Hitchcock (Rope, Rear Window, The Man Who Knew Too Much, and Vertigo), Otto Preminger (Anatomy of a Murder), John Ford (Two Rode Together and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance), Robert Aldrich (Flight of the Phoenix) and the aforementioned

Anthony Mann. But Stewart has never really let down even in bad movies, and this unrelenting professionalism and tenacity is a quality often lacking in even the greatest stage actors when they venture into the relatively fragmented screen.

All in all, Stewart has appeared in over 70 movies since his screen debut in 1935 in some forgotten Metro trifle tagged Murder Man. He was 27 then—lean, gangling, idealistic to the point of being neurotic, thoughtful to the point of being tongue-tied. The powers-that-be at Metro were slow to recognize his star potential. Through the 1930s Stewart made his biggest impact on loan-out to other studios, to Columbia for the Capras with Jean Arthur, to RKO for the Stevens with Ginger Rogers, to United Artists for Made for Each Other with Carole Lombard, to Universal for Destry Rides Again with Marlene Dietrich.

By the time Metro realized they had a prodigy on their hands, Stewart was off to the war for five years during World War II, and when he came back he had had enough of Leo the Lion and began free-lancing. He already had an Oscar on his mantelpiece for The Philadelphia Story and an award from the New York Film Critics for Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. But somehow he never regained his stride with critics and audiences. His extremely emotional performance in It’s a Wonderful Life was overlooked n a year galvanized by the classical grandeur of Laurence Olivier in Henry V and the sociological scope of the wildly overrated The Best Years of Our Lives. Magic Town was an out-and-out flop, Call Northside 777 a stolid semi-documentary, On Our Merry Trifle the occasion of a reunion with old buddy Henry Fonda in a John O’Hara sketch. Stewart later played a cameo in clown make-up for Cecil B. De Mille in The Greatest Show on Earth, but he was drifting more and more to action pictures and wacky farce comedies. In Rope, he was miscast somewhat as an irresponsible intellectual and submerged both by the lurid subject and Hitchcock’s single-take technique sans visible cuts.

But in Rear Window, The Man Who Knew Too Much and Vertigo, Stewart supplied Hitchcock with three of the most morbidly passionate performances in the history of the cinema, and again he was overlooked by critics hypnotized by the dreary Philco Playhouse realism of Paddy Chayevsky’s Marty and Terence Rattigan’s Separate Tables. This was an era in which feeble talents like Ernest Borgnine and David Niven were winning Oscars for characterizations that proclaimed their own drabness. Stewart never changed type. As he became older, he tried to look younger. Unfortunately, the best way to win awards in Hollywood is to plaster a young face with old-age make-up. Artificial aging, however grotesque it may seem to the bored camera is an infallible sign of “character” for those who confused the art of acting with the art of disguise.

Stewart, alas, was always Stewart, and he gradually slipped out of the cultural mainstream. In his personal life, he fell afoul of the redoubtable Margaret Chase Smith when he was mentioned for a general’s commission in the Air Force Reserve. In England, actors are knighted for their services. In America, they are suspected of lurid frivolity. Strategic Air Command expressed his devotion to the Air Force at a time when hawkdom was beginning to be viewed in many quarters as a potentially dangerous outlet for patriotism. The FBI Story was sickeningly reverent toward J. Edgar Hoover, and The Spirit of St. Louis somewhat pointlessly proud of Charles Lindbergh. Besides, Stewart was embarrassingly old for a part the unlamented John Kerr had turned down out of political scruples.

Through the 1950s and 1960s, Stewart had his share of clinkers. He was no happier doing the Rex Harrison stage role in Bell, Book and Candle than he had been a generation earlier doing the Laurence Olivier role in No Time for Comedy. His performance in Harvey was less effective than Frank Fay’s on the stage, and Fay operated on a fey vaudeville level over which Stewart’s screen persona usually towered. But put Stewart in the middle of good English players in No Highway in the Sky and Flight of the Phoenix and The Man Who Knew Too Much, and he dominated the proceedings as only the greatest star personalities were capable of doing. And put him in a western, and he gave it a gritty grandeur worthy of the Waynes and the Fondas and the Scotts and the Coopers.

Indeed, it was when Stewart became too old to be fashionable that he became too good to be appreciated. Suddenly his whole career came into focus as one steady stream of moral anguish. Hitchcock brought out the overt madness in him, the voyeurism (Rear Window), the vengefulness (The Man Who Knew Too Much), the obsessive romanticism (Vertigo). Ford brought out the cynic and opportunist in him. Mann brought out the vulnerable pilgrim in quest of the unknown. That Stewart even had the opportunity to enrich and expand his mythical persona into his 60s and ‘70s is a fortunate accident of film history. But enriched and expanded he has become through the steady pull of his personality which has evolved over four decades from American gangly to American Gothic. If we take care of the small matter of preserving his 70- odd films for posterity, he shall truly belong to the ages, perhaps as a relic of the moral fervor that once shaped even the more intelligent among us. In any event, the cumulative effect of all his performances is to transcend acting with being, the noblest and subtlest form of screen acting.

This was originally published in 1971.

No responses yet