Isadora Moura Mota Unearths the Fight for Freedom in Brazil

As a college student at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Assistant Professor of History Isadora Moura Mota served as a research assistant for scholar Flávio dos Santos Gomes, who studies the history of slavery in Brazil. While delving into old records at the National Archives, Mota learned for the first time about the many rebellions that enslaved Brazilians mounted in the 19th century. “I was fascinated by these stories that had been silenced for such a long time,” she says.

Mota went on to devote her own career to the study of slavery in Brazil, which was the longest-lasting slave society in the Western world, spanning from the 16th century until 1888. About 5 million people in Brazil were enslaved during that time period. “Brazil was a full-blown slave society, but its other legacy is that it was a cradle of abolitionist ideas, especially coming from the enslaved,” Mota says.

Mota’s Work: A Sampling

Mota discovered a court transcript of an 1864 trial connected to rebellions by enslaved Africans. “What survives from their activism are the legal cases against them,” she points out. The authorities devoted much effort to cracking down on the rebellions, investigating sources of funding, weapons purchases, and how ideas about freedom developed, says Mota, who studied accounts in newspapers and diplomatic correspondence in Brazil’s National Library as well as its National Archives. None of the hundreds of slave rebellions brought about emancipation, and those who were caught were punished by flogging.

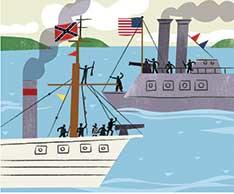

Several slave rebellions were inspired by news of the Civil War in America. Both Union and Confederate merchant ships traded with Brazil on their way to the Pacific, and when their sailors came ashore, enslaved people in Brazil learned about the abolitionist movement propelling the Civil War. Confederate and Union ships even engaged in battles along the Brazilian coast. “Afro-Brazilians saw their fate as being linked to that of other African descendants around the world,” Mota says. “If freedom was coming to Africans in the United States, it made sense that it was coming for them, too. When a Confederate cruiser and a Union ship clashed, the enslaved imagined the Union ship was coming to lend troops to their struggle for emancipation.”

A small number of Brazil’s enslaved people were literate, and they would read the newspaper aloud to others gathered in the slave quarters. Some wore necklaces with attached amulets that contained writing on slips of paper. They believed the pendants would protect them while fighting in rebellions, Mota says. Many were Muslim and wore amulets with Arabic writing inside. Occasionally, an enslaved Brazilian who was not literate would find someone who could write and dictate a letter for them, some of which have survived. “Some argue that it is impossible to write an intellectual history of the enslaved because they couldn’t leave us written records,” Mota says. “But there were many different practices of literacy that give meaning to the struggle for freedom.”

No responses yet