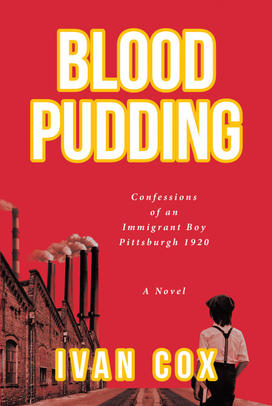

Ivan Cox/Gerald Yukevich ’68 Captures Immigrant Struggles in his New Novel

The book: Blood Pudding: Confessions of an Immigrant Boy Pittsburgh, 1920 (Fulton Books), starts with a note to readers, explaining that the book is a (fictional) long-lost memoir of Tadeusz Malinowski — the son of a Polish family that emigrated to Pittsburgh in the 1900s. Author Ivan Cox (the pen name for Gerald Yukevich ’68)’s novel tells the story of the family of nine through the eyes of Tadeusz, who wrote these accounts as a boy. He reflects on common experiences, like his struggle to integrate and the neighborhood politics, and on much darker events, including his mother’s death from a self-administered abortion. Blood Pudding transports readers to another era with this story that starts with struggle, but morphs into hope.

The Author: Ivan Cox (Gerald Yukevich ’68) is a physician and author. After graduating from Princeton with a degree in English, Yukevich graduated from the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine in 1973. He specializes in internal medicine and is affiliated with Martha’s Vineyard Hospital. In addition to Blood Pudding, Yukevich wrote Cruise Ship Doctor under his pen name Ivan Cox.

Excerpt

Note to the Reader

When my father died thirty years ago, we found this typewritten document under some stock certificates in his safe deposit box. Clipped to it was a note asking that nobody read it until 2020, one hundred years after his mother’s death. I offer this personal time capsule now, so that my father’s suffering and triumphs as an immigrant boy in Pittsburgh should be known. I suspect there are many children of immigrants to America who share a similarly gritty but ennobling legacy.

Tadeusz Malinowski Jr. Hunterton, Ohio November 3, 2020

Lightning Bugs

Mother died in November. Her sudden death left the seven of us to deal with Jumbo. Vera, the older of my two sisters, had it worst. Mother wasn’t cold in the grave six months when Jumbo started going after her. One warm evening, the next June, while I was out chasing lightning bugs, I looked back and saw Jumbo cuddling Vera on the porch swing. He was coaxing her to tug on his mustache and urging her to sip on his homemade red wine. All the while he was feeling her up. I had just turned ten. What did I know? But what I saw that night in the shadows on the porch seemed bad—his big rough miner’s hand on her blouse, squeezing her nipple. Sure, Vera was blonde and built strong and had radiant green eyes like Mother, and Jumbo must have been lonely for a woman. But Vera was fifteen, and she was his daughter. He did other stuff, too, and not just on the porch swing. Sometimes we heard Vera crying out from Jumbo’s room, like Mother had done. More than once I heard him threaten Vera that if she went up to the church and told the priest anything, he’d take his razor strop to her. I tried to pump up my courage and go to the priest myself, but I didn’t want to feel the scalding lashes of his strop either. None of us did.

I was ashamed for the family. If I told the priest and word spread around, what then? Would the mine company fire Jumbo and kick us out of the company house? Would we all be sent back to Poland? None of us talked about it. We knew what Jumbo was doing was wrong, but we were afraid to mention it. Even my big brother Max, who was sixteen and tall and brawny and quick to throw a punch, feared Jumbo. So, after Mother died, we plodded along from day to day in that crowded brick box on Robert Street in Rehoboth, Pennsylvania. We all shared grief and shame, and we wished Jumbo would stop hurting Vera. We prayed each night that he would sober up by morning and make his way to the mine. If Jumbo didn’t go to the mine, he wouldn’t get paid, and we wouldn’t eat. We each might end up in an orphanage in Pittsburgh or maybe Poland. Back on that terrible November day at the graveyard when we buried Mother, Vera announced she would quit school. “Somebody has to take her place and look after the family,” she said, her pale chin poked out and her arms cuddling little Kazzy and baby Blizzard. On the way home from the burial, Jumbo sighed. “I’m beat. I don’t feel like cooking tonight.” “I’ll do it,” Vera said. “Spaghetti.” “Can you make it like she made it?” “Taste it and see, Pop.” On that gloomy November day, Vera didn’t know what she was in for. None of us did.

Poplars

Mother’s cemetery was brand-new, almost empty. Her grave was the third they dug, set high up on a grassy hill. Half a mile down the long slope stood a straight line of young yellow-leafed poplars, separating the graveyard’s acreage from a small stone chapel with an iron fence around it. On top of the chapel steeple was a tiny iron cross. I knew Mother would enjoy that view. Often, she had told us that the rows of poplars here and there on the outskirts of Pittsburgh reminded her of Poland. Over in the old country, she said, the farm fields were separated by rows of tall poplars to shield the crops and animals from the strong winds. There wasn’t much wind that dark day by the new grave, but there was a steady cold rain. Everybody seemed in a rush to bury Mother fast and get out of it. The two cemetery workers holding the ropes dropped her so suddenly, her coffin cracked when it hit bottom. I knew that couldn’t hurt her though, because she was dead. Two nights before, I had watched her die. I was convinced that, broken coffin or not, her wonderful spirit would abide there on that hill forever, seeing the sun rise to the east and admiring the distant poplars and the stone chapel with the little cross and watching the cemetery fill up with more dead people. In church, I always heard the priests talk about heaven and purgatory and how we should pray to all the holy saints to help a person’s soul after death. But those warnings confused me.

No, I knew Mother would remain right there, overlooking the chapel and the poplars, which meant I could come back and visit her, provided I was never sent back to Poland. The older children, Max, Vera, and Lucy, had attended funerals before. They told us what to do. Ziggy and I watched them and tried to follow their cues. Once the men dropped Mother in the hole and yanked out the ropes, we each tossed a white rosebud on her and picked up handfuls of black dirt from the muddy pile and sprinkled small clods down on her. But when the workers started shoveling in big heaps of soil that banged hard on the coffin lid, Ziggy let out a loud grunt. He turned with a wild look in his eyes and took off like a shot, running down the hill. I ran after him. Mother would have wanted me to. Ziggy was two years older than me, but he was feebleminded and clumsy and had terrible eyesight and was easily upset by anything strange or different. Two years in a row, Mother had tried to start him in first grade at Rehoboth Elementary School, but each time, the teachers sent him home. The second time, bratty boys chased him all the way back to our house, shouting, “Ziggy piggy, Ziggy piggy!” They whipped his back with thorny switches and made him bleed and bawl. The teachers told Mother that sending Ziggy to school was torture for him and a waste of everyone’s time. Zig could barely tie his own shoes, let alone learn to add or subtract or read a clock or spell. School, they insisted, was futile. A state mental hospital or even the county work farm over near Beaver Run might be the proper place for him. In time, Ziggy might learn to do useful labor, they said. He would be in the company of other low IQ unfortunates, where he would feel equal and happy and possibly turn out to be productive. Mother and Jumbo had decided that sending Ziggy to a mental institution or a work farm would cast a shameful light on our family. So instead, they kept him home and with me as his keeper. Once I had mastered double knotting my own shoes and other basic grooming matters, Mother charged me with making sure Ziggy’s laces were tied right. I was also to be sure he brushed his teeth and didn’t pick his nose in public and flushed the toilet. I was to check that he buttoned his shirt straight and didn’t let his underpants creep up over his belt and didn’t leave his fly open to the breeze. I had to make sure he did not step on his eyeglasses or say odd things to the children on our street. Most of the girls were afraid of Ziggy and avoided him like a skunk or a patch of poison ivy. I also was to tell Mother whenever he wet the sheets, which was easy for me to detect, since Zig and I usually shared the same bed. These duties with Ziggy kept me from starting school in Rehoboth with the other children my age. But Lucy, or sometimes Vera, tutored me at home in reading and writing and math. Meanwhile, if any mean boys came around to taunt Ziggy, I was to tell Max immediately, who would settle scores. Mother’s death did not change my commitment to Zig. I would be there for him, and he knew it. Now that Mother had been dropped fresh in the ground, my promise seemed all the more important. When Jumbo saw us running away from the grave site, he hollered down the hill at us. By that time, we had almost reached the row of poplars and were out of breath.

Excerpted from Blood Pudding: Confessions of an Immigrant Boy Pittsburgh, 1920 by Ivan Cox. Copyright © 2022 by Ivan Cox. Reprinted with the author’s permission.

Review:

“The author does a very conscientious job of providing the innumerable period details whose careful placement serves to bring alive again the people and concerns of a long-gone decade. And it is this extended hand of hope that readers will remember.” - Steve Donoghue, Vineyard Gazette

No responses yet