Jeff Perry ’68’s Scholarship Is Elevating ‘the Father of Harlem Radicalism’

As an independent scholar, Perry has extensively chronicled the ideas of Hubert Harrison

“When I read [the books] I was totally arrested by the clarity of this thought,” Perry says. “I thought amongst all his contemporaries he was clearest on the issues of race and class.”

More than 40 years later, Perry is still studying, as an independent scholar, the life and teachings of Harrison. With the blessing of Harrison’s family, Perry has dug through more than 700 pieces of Harrison’s writing, amassed hundreds of archival boxes, and reviewed more than 7,500 books for his research.

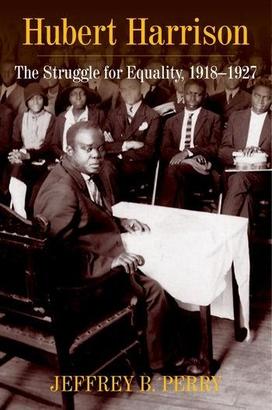

Most recently, Perry published the 1,000-page second volume of a massive biography titled Hubert Harrison: The Struggle for Equality, 1918-1927 (Columbia University Press). The book focuses on the final decade of Harrison’s life, from his writings to his activism. It ultimately illustrates the continued relevance of Harrison’s insights on various topics including race, class, and social change, which were seen as radical at the time. Perry pulled it all together, but his goal was to let Harrison’s writings speak for themselves.

Who exactly was Hubert Harrison? It’s a question Perry says he has gotten a lot. Harrison was a writer, educator, and orator who wrote extensively on race, socialism, imperialism, and much more in the early 1900s. Known as the father of Harlem radicalism, Harrison believed in empowering the working class as the way to create true social change. He founded the Liberty League of Negro-Americans, the first organization of the militant “New Negro Movement.” Its main cause was to fight for the end of segregation, abate lynching, and petition the government for a redress of grievances.

Harrison’s philosophies stand in stark contrast to many of today’s celebrated leaders of Black history, including Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois, both of whom he openly criticized. This may partially explain why Harrison’s work and teachings are largely left out of the history books. The fact that he never obtained a college degree and worked various blue-collar jobs may be another reason. Harrison’s brilliance deserves recognition among that of other prominent figures of his time, Perry says. He hopes his work will help recenter Harrison’s role in Black history.

Perry notes that Harrison’s importance has grown since he first began his research. He believes Harrison’s teachings align with some of today’s popular fights for equality, and therefore resonate with more people.

Inspired by Harrison and other working-class intellectuals, Perry completed much of this independent research while working for the U.S. Postal Service. (Harrison was also a postal worker for some time.) He was a mail handler, the head of his branch union, treasurer for the local union, and an editor for a weekly newsletter the group published. This became Perry’s own way to fight for equality as his union tackled struggles against management and organized crime.

“We were building a very significant rank-and-file movement around the principles of anti-white supremacy in terms of working-class struggles,” he says. Although it was a lot to balance, Perry says he has no regrets.

He also says his work is not yet done — even as he currently fights prostate cancer. He’d like to find a home for Harrison’s papers; to date he has placed 100 archival boxes at Columbia and another 200 at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He also has ideas for future research and writings. What ultimately motivates him, Perry says, is the hope that Harrison will finally “get the attention he merits and that people will draw from him and learn from him.”

No responses yet