Jenny Wiley Legath *08 Reveals Roots and Influence of Protestant Deaconesses

The book: As American Protestant Christianity blossomed in the late 19th century, women began looking for ways to contribute meaningfully to religious and social endeavors. Loosely modeled after Catholic nuns, the Protestant deaconess emerged as an office for women to find their place in a male-dominated world.

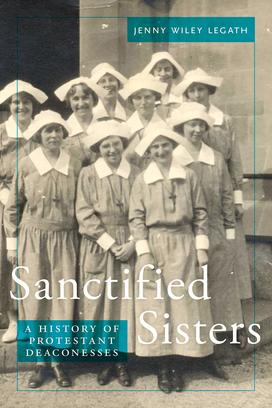

In Sanctified Sisters: A History of Protestant Deaconesses (New York University Press), Jenny Wiley Legath *08 pens the first history of these women who revitalized the role of women in the church. The diaconate allowed women a source of independence from male figures through God, and renewed their commitment to service and their faith while the question of female ordination emerged.

The author: Jenny Wiley Legath *08 is the associate director of the center for the study of religion at Princeton University.

Opening lines: At age ninety-two, Sister Ella Loew reminisced, “Across from where we lived there was a convent, and I used to admire those sisters, and I said to this old uncle, I said, ‘You know, if I was a Catholic girl, I would want to be a sister.’” Loew’s uncle surprised her with the news that their own Protestant church had sisters too, and in that moment, she knew she had found her calling. Ella Loew’s mother objected to her new mission: “Oh my, my mother had a wooden ear. She would not listen to that. So, she would suggest, you go to business college, you do that.” Yet Loew persevered in declaring her intentions, and after three years, her mother finally relented. In 1910 Loew left her home in Leavenworth, Kansas, and traveled three hundred miles east to become a deaconess probationer at the hospital in St. Louis. After four years of classes and practical nursing training, Ella Loew became a non-Catholic sister when, at the age of twenty-five, she was consecrated as a deaconess in the Evangelical Synod, a small German American Reformed denomination that later became part of the United Church of Christ. Interviewed in 1981, she happily recounted her life’s work as a nurse and her close relationship with her sisters, including the Mennonite sisters who had trained with her before going to work at their own hospital. Although Loew averred that women “are the making of the church,” when asked if she would have gone to seminary had that option been available, she answered, “No, I have never felt that was my life.” She concluded, “I have never regretted it, never. It hasn’t been all roses by any means. I’ve had any trials and tribulations, but we overcome them, too. I felt that it was a life worthwhile.” She was not alone in her calling. In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, thousands of Protestant women in the United States who sought a worthwhile life became deaconesses.

Reviews: “Legath skillfully and evenhandedly considers the deaconess movement within the social, economic, and women’s history from the latter nineteenth century to the present, providing a detailed, thorough, and unbiased work. This much-needed book is lucidly written, broad in coverage of all-American denominations, and copiously researched in primary source documents, complete with interviews of contemporary deaconesses. This will become the gold standard of work on Protestant deaconesses in the United States, indispensable for modern Christians, for students of church and women’s history, and for university and research libraries.” — Jeannine Olson, author of Deacons and Deaconesses Through the Centuries

No responses yet