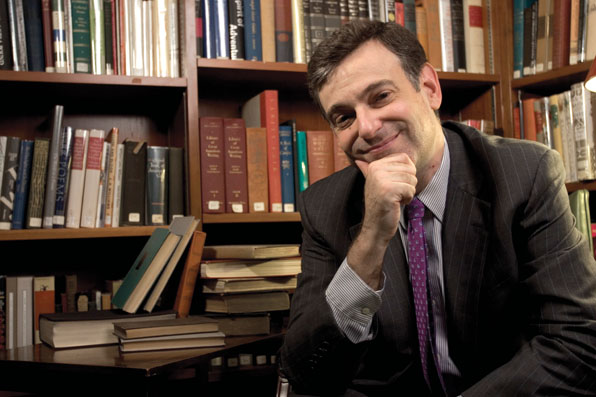

John Matteson '83 wins Pulitzer Prize in biography

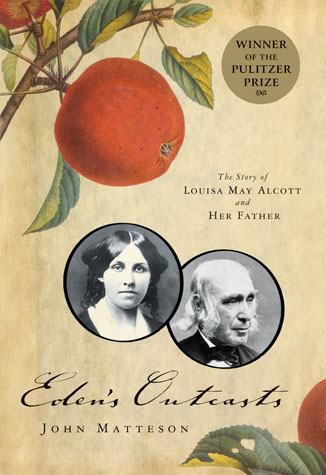

Writing a biography about the author Louisa May Alcott and her father, Bronson Alcott, not only has brought John Matteson ’83 recognition — he won the 2008 Pulitzer Prize in biography in April — but it has helped him become a better parent.

Through examining the sometimes contentious relationship between Louisa and Bronson Alcott in Eden’s Outcasts: The Story of Louisa May Alcott and Her Father (W.W. Norton, 2007), Matteson says he learned how to better listen to and communicate with his own daughter. A lecturer, philosopher, teacher, and friend of Emerson and Thoreau, Bronson Alcott believed education was about drawing out children and not cramming in information. “His method of teaching,” says Matteson, whose daughter was 7 when he began research in 2001 on the book, “was to try to seek out what he thought was the divine spark within the nature of a child.”

Bronson Alcott, an “easygoing, placid, almost passive man,” experienced setbacks, including a failed attempt at building the utopian community of Fruitlands, Matteson says. Alcott could not understand how his parenting methods could produce a child “who was so uncontrollable” as Louisa, “a very aggressive, assertive tomboy who was always getting into all kinds of trouble,” explains Matteson. An associate professor of English at the City College of New York’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice and a history major at Princeton, Matteson sees the Alcotts’ story as one of redemption. Although the father’s failures almost destroyed his worldly fortunes and the family lived in poverty for many years, “he basically never gave up,” says Matteson. In her father’s eyes, Louisa redeemed herself by her writing success and her nursing work in the Civil War.

Matteson was “absolutely dumbfounded” to learn Eden’s Outcasts had won the Pulitzer Prize. He was in a faculty meeting when a colleague tapped him on the shoulder, telling him he had to “leave this meeting immediately — it’s an emergency,” he recalls. “I walked out wondering who had died.”

A specialist in 19th-century Ameri-can literature, Matteson pored through Bronson Alcott’s diaries and those of his daughters. Matteson also spent a lot of time talking with his own daughter “to figure out how a young girl would respond to a very idealistic and high-minded but also at times distant and difficult father.” Matteson will appear as a commentator in a PBS documentary on Louisa May Alcott that is nearing completion.

Matteson has begun work on his next book, a biography of the 19th-century journalist, literary critic, and women’s-rights advocate Margaret Fuller. “I feel that I’ve found a very comfortable home in biography,” says Matteson. “I would love to write novels, but seemingly do not have the imagination for original plot lines. So give me an archive and a set of facts, and I’ll tell you a story.”

No responses yet