Jon Wiener ’66 on LA Activism in the 1960s

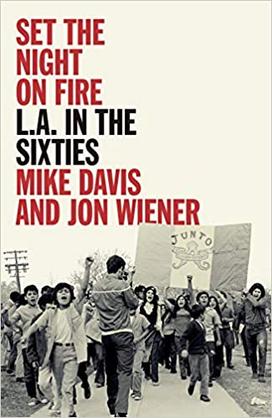

The book: Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties (Verso) is an in-depth look at the history of 1960's Los Angeles from the perspective of several activist movements of the time, including civil rights, anti-war, gay liberation, and the women's movement. From Malcom X and Angela Davis to Chicano Blowouts, and the California counterculture LA was a hotbed of political and social activism.

The authors: Jon Wiener ’66 is a longtime contributing editor at the Nation and the host and producer of Start Making Sense, the magazine’s weekly podcast. He is an emeritus professor of U.S. history at UC Irvine, and his books include Gimme Some Truth: The John Lennon FBI Files and How We Forgot the Cold War: A Historical Journey across America. He lives in Los Angeles.

Mike Davis is the author of City of Quartz, Late Victorian Holocausts, Buda’s Wagon, and Planet of Slums. He is the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship and the Lannan Literary Award. He lives in San Diego.

First behind the plow were Black students in the South, whose movement would name itself the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The lunch counter sit-ins in February began as quiet protests but soon became thunderclaps heralding the arrival of a new, uncompromising generation on the frontline of the battle against segregation. The continuing eruption of student protest across the South reinvigorated the wounded movement led by Dr. King and was echoed in the North by picket lines, boycotts and the growth of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Separately, the Nation of Islam grew rapidly, and the powerful voice of Malcolm X began to be heard nationally. Meanwhile, as the United States continued to install ICBMs in Europe, the growing revolt against nuclear weapons, as historian Lawrence Wittner put it, “signaled an end to the Cold War lockstep among sizable segments of the American population ... the peace movement by 1960 had been reestablished as a significant social movement.” The same could be said for student activism and radical scholarship at some of the major Cold War universities. Progressive campus organizations such as SLATE at UC Berkeley (the precursor of the Free Speech Movement) and VOICE at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor dramatically broke the ice of student apathy, while journals like Studies on the Left (founded in 1959 in Madison) and New University Thought (Ann Arbor/Detroit 1960) gave voice

to what everyone was soon calling the “New Left.”

A young generation was waking up in Southern California as well, despite the stunted character of political and intellectual life in most of the region, and the year 1960 previewed the social forces, ideas, and issues that would coalesce into “movements” over the course of the next decade. This chapter follows month by month the emergence of a new agenda for social change and introduces some of the key actors and organizations. “Agenda” in this case meant something more than a simple menu of issues and causes. Indeed, events and protests in 1960 also delineated the “issue of issues”: the dynamic tectonics of racial segregation that were shaping the future of Southern California. With the benediction of federal lenders and the full complicity of the real estate and construction industries, racially exclusive suburbanization was creating a monochromatic society from which Blacks were excluded and in which Chicanos had only a marginal place. The legal victories for civil rights won in the late 1940s and early 1950s had yet to yield edible fruit. In a booming regional economy, irrigated by billions of dollars of military spending, minorities possessed little more than low-skill toeholds in the region’s three major industries: aerospace/electronics, motion pictures, and construction. Los Angeles schools, meanwhile, segregated more students than any Southern city, and as far as most residents of South Central L.A. were concerned, the LAPD might as well have flown a Confederate battle flag outside its new “glass house.”

Review: “The familiar, monochromatic picture of Los Angeles in the sixties — all Hollywood pop and Didion ennui — required a million people of African, Asian, and Mexican ancestry to be ‘edited out of utopia,’ as Mike Davis and Jon Wiener put it. What those people actually did, alongside antiwar feminists, high school students, and others, is the heart of this book, and it’s a big heart. No one could tell these intersecting stories better than Davis and Wiener, and their book gives us back a great city’s greatness in its movements, edges, and other centers, so many of them forgotten.” —Rebecca Solnit, author of Recollections of My Nonexistence: A Memoir

No responses yet