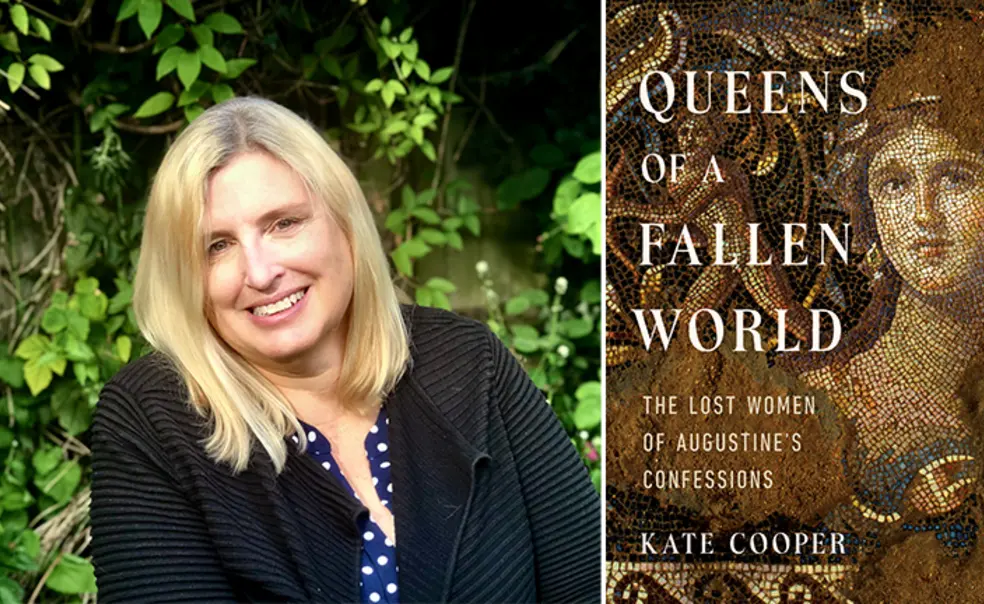

Kate Cooper *93 Draws Out the Women in Augustine’s ‘Confessions’

In her new book, Cooper analyzes Augustine’s mother, concubine, and fiance

Kate Cooper *93 has grappled with Augustine’s Confessions since she first read the book as a graduate student in 1984. This year, she published Queens of a Fallen World: The Lost Women of Augustine’s Confessions, in which she considers the women in the autobiography of one of the most influential figures in medieval Latin Christianity, as Cooper describes Augustine.

The book, Cooper says, “reveals how carefully Augustine watched and listened to the women in his life, and how much he learned from them.”

His mother Monnica is one of the best-known women in the early church, second only to the Virgin Mary, Cooper says, and is a significant character in Confessions. But Augustine barely mentions his longtime concubine or the young girl betrothed to him, which created a major interpretive challenge for Cooper, who specializes in late antiquity as professor of history at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Cooper graduated from Wesleyan in 1982 and earned a master’s degree in theological studies from Harvard in 1986 before coming to Princeton that fall to study with Peter Brown, the author of Augustine of Hippo, the standard modern biography of the subject. Cooper’s first essay for Brown’s seminar on the origins of the Middle Ages was, she says now, an attempt “to get my head around Augustine and women.”

Cooper persisted in that effort. She planned to include a chapter on Monnica in her 2013 book Band of Angels: The Forgotten World of Early Christian Women, but that chapter instead developed into Queens of a Fallen World. “I realized you couldn’t understand Monnica without understanding Una, Augustine’s concubine,” Cooper says. “And I was always fascinated by Tacita, the girl to whom Augustine was engaged.”

From the first time Cooper read Confessions, she says, “What interested me most was the way it gave you a window into the family relationships in Augustine’s early life.” She explores that aspect of the work in her new book.

But almost nothing is known about Tacita and Una — Augustine doesn’t even give them proper names. (Una is the Latin word for “one” or “someone,” while Tacita is Latin for “the silent one.”) To tell their stories, Cooper says, she used a historical method which she calls critical speculation. “This doesn’t mean you can contradict the evidence,” she says, “but you want to push the evidence as far as it will go, to lay out as many possibilities of what might have been as you can.”

Ambitious young men like Augustine often took concubines while deferring marriage. He and Una were together from their late teens, and soon after they became a couple, she bore him a son, Adeodatus, whom Augustine deeply loved. But Monnica was socially and politically ambitious, and she arranged a marriage for her son with Tacita, an heiress whose dowry could fund Augustine’s political career.

Tacita was only 10 years old, and since 12 was the minimum age of marriage for girls under Roman law, she and Augustine would have had to wait two years to wed. Tacita’s parents made Una’s return to Africa a condition of the engagement.

The separation threw Augustine into a spiritual crisis. Cooper quotes the words he wrote in Confessions: “The woman I had been sharing a bed with was torn from my side, and my heart, which clung to her, was cut and wounded and bleeding.”

Augustine renounced his engagement to Tacita and returned to Africa with Adeodatus, who died soon thereafter. There Augustine would become a bishop and theologian, a role in which his own experiences may have helped shape the views he adopted. “In his pastoral work,” Cooper says, “Augustine came face to face with the harsh treatment women suffered in Roman society, and he became the champion of a view of marriage which saw women and men as equal before God.”

No responses yet