Keisha Blain *14 Creates a ‘Primary Source’ for Black Voices

In a new book, Blain hopes to capture for future historians what Black people in the U.S. are thinking now

“It was at that moment I thought, ‘There’s something that connects us,’” she says.

Later, as an undergraduate at Binghamton University, Blain heard lectures about key figures and developments in Black history she’d never heard of before. At first her lack of knowledge made her feel ashamed, but then she came to an important conclusion: If she didn’t know about this history, it meant no one was teaching it. That realization helped redirect her career plans away from law school and toward teaching the history of Black people and other marginalized populations.

Today, Blain, who earned a master’s and a Ph.D. in history, along with graduate certificates in African American Studies and Gender & Sexuality Studies at Princeton, is a history professor at the University of Pittsburgh and president of the African American Intellectual History Society. She is currently a fellow at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at Harvard. In 2018 she authored Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom. It made The Washington Post’s list of “13 books on the history of Black America for those who really want to learn.”

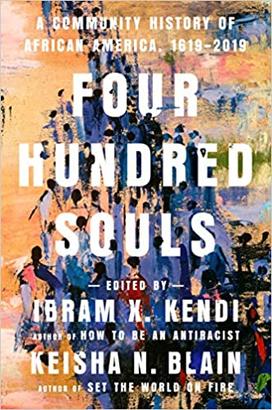

Now, with Ibram Xendi, director and founder of Boston University’s Center for Antiracist Research, Blain has co-edited Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019 (Random House). Featuring the work of 90 writers, the book tells the story of African Americans’ 400-year journey, beginning with the start of slavery in America, in Virginia in 1619.

“We wanted to capture the history of 400 years. But we also wanted to create history, in the sense that we saw the book as a sort of primary source that historians of the future would be able to turn to, if they want to capture what Black people in the United States were thinking, how they were grappling with the challenges of COVID-19 and the Trump presidency and police violence,” Blaine says. “They would be able to turn to Four Hundred Souls and have a snapshot of what Black people from different backgrounds were thinking and feeling in these critical years.”

It was a strategy for forcing authors to do something quite different than they normally would for a standard textbook or a standard edited volume, she says.

In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, Blaine says African Americans are in a difficult moment. “There are a number of challenges that we are still facing as a nation, particularly police violence and brutality and, of course, racial disparity when we think about how COVID-19 has impacted Black communities in particular. There are still so many hurdles for us to come over.”

But with the election of Joe Biden as president, Blaine also sees hope — and a challenge to face.

“My sense is that with the Biden administration, there is some hope that we’ll begin to see changes, particularly as it relates to federal policies that could, in fact, improve the lives of Black people,” she says. “At the same time, this is a moment where we have to keep fighting and keep demanding changes. We can’t sit back and be complacent and simply celebrate that there are now people in leadership who have expressed a commitment to many of the ideals that we hold dear. Instead, we have to now make sure that whatever promises were made are actually fulfilled.”

No responses yet